At 5.15pm on Tuesday 31 May 2022, a group of four, including Éric Bonnem, founder of Secret Planet and Expeditions Unlimited, reached the summit of Mount Denali at 6,190 meters. A wild and beautiful expedition, which we'll be reporting on shortly, and which gave us the urge to delve back into the history of the first mountaineers to have trodden this superb mountain almost 110 years earlier, in far more heroic conditions! Mount McKinley... Denali. The highest mountain in North America, dominating the icy Yukon, has had a tumultuous history. Unlike most of the great peaks, the first men to set foot on its summit were not skilled mountaineers, but humble prospectors, led by a priest animated by a mystical faith. Walter Harper, a half-breed with Indian blood, Roger Tatum, Harry Karstens and the priest Hudson Stuck did not hesitate, despite their lack of mountain experience, to take on the giant of North America. A look back at the conquest of the ‘roof of North America’.

See all the climbs of the Seven Summits challenge.

Alaska, land of Russia

In 1794, at the age of 37, Captain George Vancouver, in command of two imposing sailing ships of the Royal Navy, sailed up the Russian waters of Cook Gulf, at the bottom of which the town of Anchorage was to be established. To his astonishment, a line of ‘mountains of prodigious height’ lined the horizon. In search of the mythical North-West Passage, Vancouver didn't bother to assess their height: these unknown lands, the property of the ‘Tsar of all the Russias’, would have to wait until 1867 before changing hands and becoming the last state in the Union of the United States of America.

In 1878, two trappers, Alfred Mayo and Arthur Harper, went 480 kilometres into the interior. On their return, they announced that they had discovered gold. The rush was immediate. But the prospectors were interested in the rivers, not the mountains. William Dickey, a university student who set off in 1896 to discover the Far North, was the first to estimate the altitude of the mountain that the Indians living at its foot called Denali (the great mountain): 6,096 metres. Very close to today's measurement. Back in civilisation, Deckey learned of the election of William McKinley, Senator from Ohio, as the 25th President of the United States. In his honour, Deckey named the highest mountain on the North American continent ‘Mount McKinley’.

Named, measured, it remains to be climbed...

Frederick Cook, unrepentant forger

Several prospectors were exploring the area around McKinley. Some were eager to climb its slopes. In 1903, at the age of 38, Frederick Cook, a doctor by trade, embarked on an adventure: he wanted to be the first to climb the highest peak in the United States of America. He took on the southern slope, the easiest to reach from Anchorage, but also the steepest. He skirted the massif for 160 kilometres, without finding the slightest fault.

Frédérick Cook, forger of Denali and the North Pole!

Three years later, he made another attempt. This time, he claimed victory and announced that he had reached the summit... via the south face, with Ed Barrill as his companion on the last day. But there were too many inconsistencies in his story. Accepted in New York, his version was strongly questioned by one of his team-mates, Belmore Browne, who remained at the foot of the mountain. In 1909, Ed Barrill denounced the forgery. In 1906, Cook claimed to have reached the North Pole, before the success was attributed to the explorer Peary.

Miners and prospectors rise to the challenge

If the ‘scientists’ with their sophisticated equipment don't succeed, the prospectors think they can: they know the terrain and know how to endure difficult conditions. As far as they were concerned, only the northern slope offered any chance of success. In February 1910, six experienced miners and prospectors tried their luck. Among them was a certain Charles McGonagall. Although they failed to reach the summit, the team discovered the col, the key to the long, debonair Muldrow glacier. It has since been known as McGonagall Pass. On 10 April 1910, they finally entered the upper basin of the glacier, at around 5,500 metres. William Taylor and Peter Andersen, at their best, equipped with rudimentary crampons and long poles as ice axes, managed to reach the north summit at 5,934 metres. It was getting late, and the south summit at 6,190 metres was out of reach. But they had opened the way to victory.

Parker - Browne narrowly escape the 1912 earthquake

In 1912, the expedition led by Professor Parker and Belmore Browne turned back just a few meters from the summit due to extreme weather conditions. It was a painful decision at the time, but one to which they certainly owed their lives: a terrible earthquake of magnitude 7.4 shook the mountain the day after they returned to base camp. The ridge they had climbed to reach the upper basin of the glacier was turned upside down.

Belmore Brown had to turn back in 1912, 60 meters below the summit because of the storm.

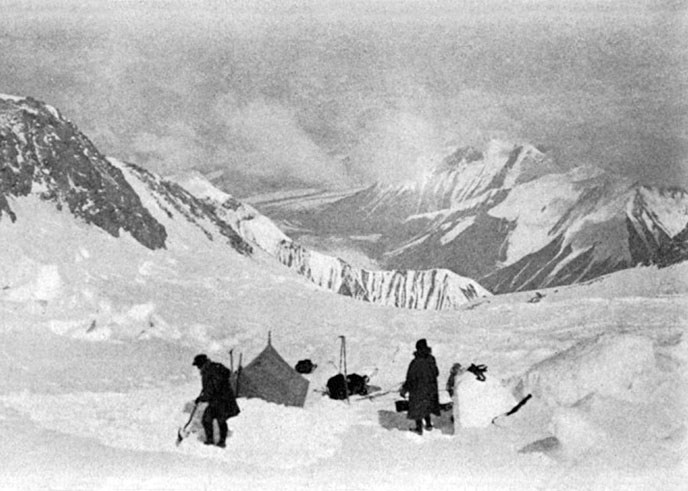

Photo taken during Belmore Browne's attempt in 1912

Photo taken during Belmore Browne's attempt in 1912

1913: the year of victory

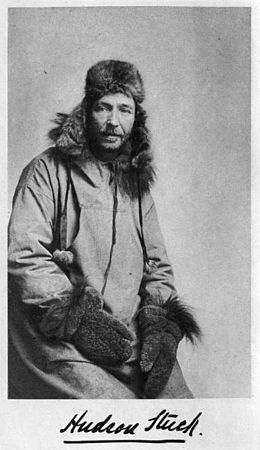

At the age of 50, Hudson Stuck, a priest who, in his own words, was ‘not an explorer, mountaineer or scientist, but a missionary’, was bewitched by Denali. For years, he has been travelling the immense diocese of Alaska. For Stuck, climbing Denali would be a godsend. This veteran of fearsome winters has little doubt that he will succeed. He surrounded himself with a team of three young, robust prospectors: Roger Tatum (21), Walter Harper (21) and Harry Karstens (34).

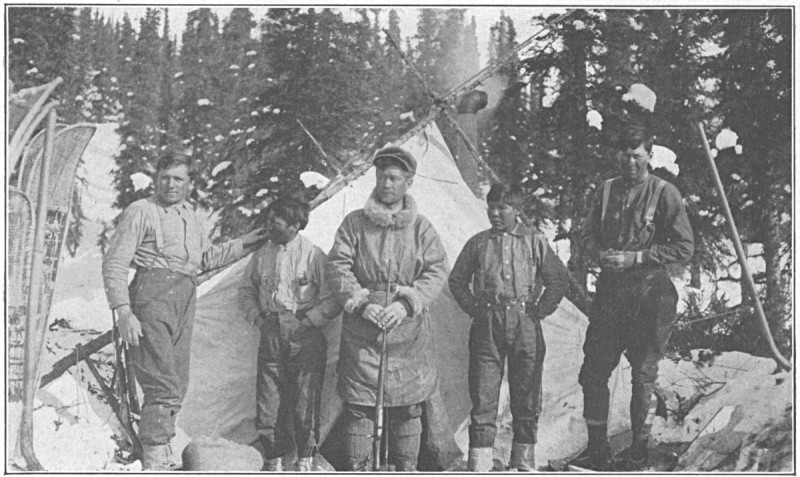

From left to right: Roger Tatum, Johnny, Hudson Stuck, Esaias, Harry Karstens.

From left to right: Roger Tatum, Johnny, Hudson Stuck, Esaias, Harry Karstens.

Photo by Walter Harper © Hudson Stuck

Hudson Stuck, in the course of his various peregrinations in Alaska, had become convinced of the imperative need to arrive directly from the north in order to repeat the route of the last two expeditions of 1910 and 1912. These expeditions set off from the southern coast, near Anchorage, and had largely exhausted their forces before even beginning the actual ascent.

Sledging from the shores of Lake Minchumina to the Kantishna mining camp © Hudson Stuck

Sledging from the shores of Lake Minchumina to the Kantishna mining camp © Hudson Stuck

On 17 March 1913, the entire team left the shores of Lake Minchumina, in whose waters Denali was reflected: two sledges loaded with 700 kilos of provisions, fourteen dogs, four ‘mountaineers’ and two Amerindian helpers, Esaias and Johnny. Esaias will bring one of the teams back from the base camp. The second will be in charge of looking after the dogs at the same camp: he will remain alone for almost two months, unsure of whether he will succeed. In mid-April, the four ‘mountaineers’ crossed McGonagall Pass (1,774 m) and set foot on the Muldrow glacier.

A dangerous climb as a result of the earthquake

The climb could have been relatively straightforward. But the earthquake of 1912 changed the face of the route considerably. For days, the four men had to make their way through blocks of ice and gaping crevasses. A relatively easy ridge required great precautions: they had not provided fixed ropes to equip the passages on the way down. The weight of the loads to be carried, almost 140 kilos for each of the four protagonists, meant that they had to make several successive trips up and down.

Grand bassin, camp 2 © Projet Gutenberg

Walter Harper, the forgotten hero of Denali

One of the participants quickly stood out for his qualities and stamina: Walter Harper. The son of an Alaskan Indian woman and the prospector Arthur Walter (the initiator of the 1878 gold rush), this elegant young man with haughty features would carry the honour of his forebears high.

Walter Harper, son of an Alaskan Indian woman and a prospector © Walter Harper, 1916

(Photo courtesy of UAF Rasmuson library)

At 3am on 6 June, the four of them left the last camp set up in the upper basin of the Muldrow glacier at around 5,500 metres. Stuck, convinced that God was watching over them, was strengthened in his mystical feeling: they had been granted twenty-four hours of exceptional, cloudless weather. Not to mention the fact that at this latitude, almost six thousand meters above sea level, the sun never sets. Only the intense cold (-14° with wind) slowed their progress: they had to stop frequently to restore circulation to their icy limbs.

On 6 June 1913, at 1.30 pm, the young Amerindian Walter Harper stepped onto the summit of Alaska's highest peak. Hudson Stuck, the last man on the summit, was finding it increasingly difficult to cope with the meters of altitude. He almost fainted, and it was Walter's helping arm that held him up. Allelujah! Stuck: ‘I had the feeling that I had been granted the privilege of communing with the highest places on earth’.

An emotional Te Deum crowned the success. And despite their exhaustion, they stayed at the summit for an hour and a half, taking scientific measurements using the heavy, cumbersome instruments they had laboriously carried up the mountain.

At 3pm, they finally left the summit. It was a perilous journey back through the blocks of ice before returning to the valley. The journey to the Kantishna mining camp is far from easy, with swollen torrents and swarms of mosquitoes.

False prediction

While Hudson Stuck deserves credit for completing this first ascent, his sense of alpine prediction makes us smile: ‘The perspective we had [of the summit] agrees with our study during the ascent that no other route to the summit will be found’.

The West Buttress Route (1951), shorter than the original route via the Muldrow glacier, became the classic route. The impressive South Face of Denali was climbed in 1961 by the Italian mountaineer Ricardo Cassin (1909-2009).

Hudson Stuck, equipped for extreme cold.

Plea in favour of the Alaskan Indians

Hudson Stuck's mysticism was accompanied by an ethic that was ahead of its time. "It may be that the Alaskan Indians are doomed [...] it is common to meet white men who complacently assume this. Those who fight heart and soul for the Natives do not believe it. [...] But if that's the way it has to be, let's at least let the memory of the old names live on".

From 1975 onwards, controversy raged over the mountain's name. On 30 August 2015, US President Barack Obama announced the official naming of Denali. The memory of old names, so dear to Hudson Stuck, lives on.

Climb Mount Denali at 6,190 meters in Alaska, highest peak of North America.

And discover below an animation showing the ascent of Mount Denali:

Text and animation by Didier Mille

Climb Denali at...

Climb Mount Denali at 6190 meters in Alaska

Ascent of Kilimanjaro at 5895 meters Machame route

Expeditions Unlimited blog

Expeditions Unlimited blog