Drowned in the equatorial mist, the Carstensz Pyramid, 4,884 meters high, located in Indonesian New Guinea (Irian Jaya), was only climbed in 1962. Known since the 17th century, protected by an almost inaccessible barrier of virgin forest, it has long resisted the onslaught of Europeans. The highest peak in Oceania, its ascent completes the challenge of the Seven Summits, the seven highest peaks on the continents. A look back at the history of the exploration and conquest of Puncak Jaya.

See all the climbs of the Seven Summits challenge.

Carstensz pyramid, north side © Jean-Luc Rigaux

The discovery of the Carstensz pyramid

February 1623. Terrorized, the white men flee to the beach. Out of the forest, pitiless little men armed with huge bows, their faces painted, a bone across their nose or lips, rush at them. Skulls burst like gourds, the wounded stagger under the bite of sharp arrows. Within minutes, the fishing trip planned by the captain of the Arhem turns into a tragedy. Year in, year out, of the fifteen sailors and officers aboard the pinnace, nine managed to make it back to shore. Among them, the captain was seriously injured. He died 48 hours later. The defeated, abandoned on the beach, will most likely be used as a feast by Papuans already renowned for their anthropophagy.

© Jean-Luc Rigaux

The Papuans sometimes ate the body of their great enemy, to appropriate his strength. The Western imagination has largely exaggerated these anthropophagic rites, because, on the whole, they were rather fearful and respectful of the whites, who massacred them without the slightest hesitation.

A few hours earlier

The two ships led by Dutch explorer Jan Carstensz, the Arhem and the Pera, sailed in the Arafura Sea, along the southwest coast of the island then known as New Guinea, discovered in the 16th century by Portuguese and Spanish navigators en route to the Pacific. Europeans had yet to set foot on the island. On February 11, the captain of the Arhem took the initiative to disembark with fifteen men, without waiting for authorization from the commander, Jan Carstensz. The first encounter with the Papuans turned out badly. The captain of the Arhem died of his wounds, missing the “highlight” of the voyage.

On February 16, the two ships dropped anchor in a bay on the south coast. Carstensz: “We were about three kilometers from land. At a distance estimated at about 15 kilometers inland, we saw a very high mountain range, white with snow. An extremely unusual sight, given our proximity to the equinox. The Carstensz pyramid had just been discovered, one of the few snow-capped peaks in Ecuador's latitude. Upon his return, Jan Carstensz's story was greeted with incredulity. As for Papua, its name derives from a Malay word referring to the frizzy hair of the Melanesians.

The Wollaston expedition

It wasn't until the early 20th century that Europeans took a serious interest in these Snow Moutains, whose existence was finally recognized. Alexander Frederick Richmond “Sandy” Wollaston, explorer since the age of 23 and occasional mountaineer, was familiar with the equatorial mountains, their climate and their fauna. A botanist, entomologist and physician, in 1905 he took part in an expedition organized by the British Museum to the Ruwenzori Mountains in West Africa, on the border between Uganda and the Belgian Congo. As a result, he was selected by the Museum to join the 1910-1911 expedition to New Guinea. Objective: to approach the Dungudungu or Snow Mountains Range. Six naturalists, under the command of a Dutch lieutenant and a cohort of soldiers, 60 convicts and a hundred coolies specially sent from India for the occasion, faced terrible conditions. Setting out from the Mimika Coast (south coast), with fevers decimating the men one by one, they struggled for months to approach the mountain. After a whole year of misery and tragedy, they had to give up.

The penis case, a real ornament, is characteristic of the Papuans of New Guinea © Jean-Luc Rigaux

In 1912, Wollaston is back. This time, Dayak guides, hired from the nearby island of Borneo, were at his side. Stronger and more efficient than the locals, they helped them reach the foot of the mountain... in 183 days from the Mimika Coast! The climb begins. They improvise rattan ropes! Wollaston: “The weight of the men causes the vegetation to slip on the smooth rocks (...) it would take a lot to cause an avalanche. Later: “We had to make a makeshift bridge using a sapling thrown from rock to rock, as flexible as a fishing rod...”. But they were gaining ground, gaining a foothold on the snow. “The Carstensz towered just above our heads, within reach. But it was mid-day, too late to go any further.” They turned back. Their meter read 4,600 meters. On the way back, Wollaston and his Dayak guides descend the river in a makeshift canoe. They fall into a rapid. Wollaston narrowly escapes drowning. End of story.

.png)

Wollaston, 37 in 1912, on his first expedition to New Guinea © Nicolas Wollaston

Copper and gold: a curse for the Papuans

Between 1920 and 1930, around one million indigenous people survived in the highlands of New Guinea. Conditions were close to Neolithic, to the Stone Age to be precise. They knew neither iron nor the wheel. The outside world knew almost nothing of their existence. The first Europeans to approach them for months on end were gold prospectors from nearby Australia.

.png)

Until 1960, the only known tools came from stone-cutting. © Heinrich Harrer

In 1926, the first gold deposits were discovered. A veritable gold rush ensued, with Papuans shamefully exploited to extract the mineral that drives people mad. This was only the beginning of their misfortune. Later came copper. A sad benefit for mountaineers: to exploit these riches, makeshift airstrips are built in the jungle, providing easier access to the high plateaus.

Michel Leahy, one of the most famous gold prospectors of the 1930s

1936: three Batavians at the summit of the secondary peak

In the early 1930s, Igor Sikorsky, a brilliant Ukrainian engineer who had emigrated to the USA, developed a seaplane, the Sikorski S-38, capable of flying at very low altitudes. In 1936, three scientists commissioned by the Royal Netherlands Geographical Society to explore the Dungudungu range used this aeronautical marvel.

.jpeg)

The Sikorski S-38 perfect for flights over New Guinea © Aviadéjàvu

The team included a Frenchman: geologist Jean-Jacques Dozy. The Papuans will not soon forget his name. Reconnaissance flights found a much shorter access route than the one previously used from the remote Mimika Coast. And the seaplane brought freight in almost unlimited quantities. After a 57-day approach, they were ready to go. They climbed the obvious snow dome, the Nga Pulu, which rises to 4,862 meters. They were certain they had reached Papua's highest point. Victory! Well, almost... Because the following year, precise triangulation calculations revealed that the rocky summit on the opposite side of the valley reached 4,884 meters, i.e. 24 meters higher. Everything had to be redone. During the expedition, however, Dozy took numerous samples. Close to the mountain, he discovered a copper deposit with a maximum grade of 4% pure ore. The usual grade varies between 0.4% and 1%. The Papuans' fragile natural habitat is no match for this gigantic deposit.

.jpeg)

Freeport, the sixth largest open-pit mine in the world.

In operation since 1963 for the extraction of gold and copper © JungleKey

Heinrich Harrer: the Dalai Lama's tutor at the top of the Carstensz pyramid

Known in France for his book Sept ans d'aventures au Tibet (Seven years of adventures in Tibet), the Austrian Heinrich Harrer scored a major victory. At 2pm on 13 February 1962, he climbed to the top of the main summit of Carstensz with his three companions, whose memory has not been preserved in history. To a fault. At least for the youngest of them, New Zealander Philip Temple, without whom the ascent would probably not have been a success. In 1961, a New Zealand expedition led by Colin Putt made an unsuccessful attempt to reach the mountain. Logistical difficulties led to failure. Harrer called on Philip Temple, one of the participants whose experience would prove invaluable. They set off from Hollandia on the north coast, flying to Ilaga to the east of the Carstensz pyramid. On 2 February, with their Dani porters, they crossed a pass at 4,500 metres, which they named the New Zealand Pass, in honour of their predecessors. In possession of photos taken during the 1936 attempt, Harrer was appalled by the glacial retreat: 500 meters lost. 700 meters for the Meren glacier, seen by Jan Carstensz in 1623.

.png)

The misty pyramid Heinrich Harrer

On 11 February, wading through deep, heavy snow, they made their second ascent of Nga Pulu. On the 13th, they made their final attempt on the pyramid. There were some serious climbing passages in their way, but their mountaineering experience enabled them to climb them without difficulty. Once they reached the ridge, they had to negotiate a number of jumps over a distance of half a kilometre. Harrer: ‘The summit is a narrow cone of snow on which four of us could stand. We hung up our respective flags. Holland, Papua, Australia, New Zealand and finally Austria.

.png)

North face of the Carstensz pyramid © Heinrich Harrer

© Jean-Luc Rigaux

Today, the plane makes it easy to reach Ilaga, the starting point for the trek to the Carstensz pyramid.

The French premiere

On 6 January 1979, high mountain guides Bernard Domenech and Jean Fabre became the first Frenchmen to climb the Carstensz pyramid. Their 45-day expedition, admirably recounted with caustic humour by Jean Fabre, took place at a time when the Indonesian government was waging a veritable war of extermination against the Papuans. The story, full of administrative twists and turns and disillusionment with the ‘green hell’, is not short of salt. A must-read, whether you are a candidate for the Carstensz or not.

Jean Pierre Frachon, the man behind the Gallic Seven Summits

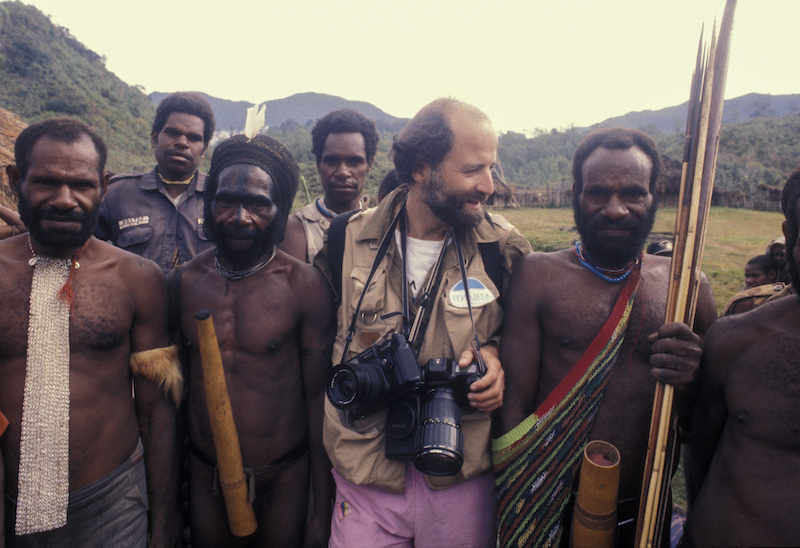

On 27 November 1991, Jean-Pierre Frachon and photographer Jean-Luc Rigaux also reached the summit. With this success, Jean-Pierre Frachon became the first Frenchman to achieve the Seven Summits challenge, and the 3rd in the world.

Jean-Luc back from the climb © Jean-Luc Rigaux

Variable toponymy

The Carstensz pyramid bears different names, reflecting the turbulent history of New Guinea. Firstly, Cartenzpiramide in Dutch, in honour of the navigator Jan Carstenszoom, who first saw it. When Indonesia became independent in 1949, the western part of the island remained under Dutch control, before becoming part of Indonesia in 1963. The mountain was renamed Puncak Soekarno in honour of Indonesia's first president. But the communists adopted the name Puncak Jaya (Victory Peak). The Papuans call it Dungudungu (the mountain) and its snowy neighbour Namangkawee (white arrow).

Climb Carstensz Pyramid at 4884 meters in Papua, highest peak of Oceania.

Text by Didier Mille.

Climb Carstensz Pyramid at 4884 meters in Papua, highest peak of Oceania

Climb Aconcagua at 6962 meters standard route in Argentina

Expeditions Unlimited blog

Expeditions Unlimited blog