Jean-François Descat's Diary

In the summer of 2024, Expeditions Unlimited had the opportunity to accompany Jean-François Descat and Julien Delteil, two experienced mountaineers, on their first expedition to very high altitude: the ascent of Broad Peak at 8047 meters in Pakistan. The ascent of this great mountain, located just opposite K2, is often given as accessible when in fact it is not, notably due to its steepness and the often capricious Karakorum weather. This blog post is Jean-François' account of his unparalleled adventure, an 8000-meter ascent in Pakistan.

Find out more about our ascent of Broad Peak, guaranteed departure June 13, 2025

Meeting with Jean-François Descat and Julien Delteil

We were contacted by Jean-François Descat in the spring of 2022, when he and his long-time companion, Julien Delteil, were preparing to climb Korjenveskaya, a 7105-meter peak in the Snow Leopard challenge in Tajikistan. It was their first step towards high altitude. Very interested in this summit, and with Serge Bazin guiding it the following year, we lent the duo some equipment and put a little oil in the Kyrgyz-Tajik wheels of the partner we know well. This first run was a success and Jef and Julien returned with a wealth of information, photos and advice, which they then shared with us, helping us greatly to reach the summit on August 19, 2023 with Serge and four other climbers.

So when Jef came back to us with this Broad Peak project, there was no question of not being part of it. We decided to lend them high-altitude tents, down suits, Iridium InReach communication and safety equipment and a telephone. We then contributed to the logistical preparations and implementation in Pakistan. Finally, drawing on our experience at 8000 meters, we advised them on logistical and strategic preparations (acclimatization, oxygen, portage, etc.) and provided weather routing in the person of Dominique Hennequin. Throughout their expedition, we had the good fortune to have a front-row seat, exchanging messages with them almost daily, and to experience their adventure 100%.

This story now belongs entirely to them. It's the story Jean-François tells you in this diary, the story of two friends, two talented and self-sufficient mountaineers.

Julien at camp 2 of Broad Peak © Jean-François Descat

Choosing our first 8000

“I want to discover the world through its mountains”. I must have said something like that to Clémence on the terrace of a café, nearly twenty years ago. And here I am, writing these sentences in Pakistan, at the foot of Broad Peak.

“At least one summit at 8000 meters. This idea matured in my mind during a trip to Peru in 2018, and I remember formulating it to Julien in the famous restaurant “chez Patrick” in Huaraz.

The following years, on the summit of Les Droites, I achieved my 82nd 4000 with him, and we stood on the summit of Korjenevskaya at 7150 meters.

If I were to climb a peak in excess of 8000 meters, it would be the culmination of a long apprenticeship in high-altitude and long-distance travel. The 8000 would top a pyramid whose base and heart are made of the rocks of the Alps, and the upper floors of the snows of the Andes and Pamir. At the heart of this pyramid teem as many faces, French, Italian, Swiss, Quechua, Aymara, Russian, Tajik, speaking different languages, different dialects, who have told me about the world as they have told me about their mountains.

But which 8000? As always, we only have a small budget, we're dependent on school vacations, we want to be self-sufficient and we want to enhance our high-altitude adventures with a superb trek that we could cover with our companions.

In July 2017, at the Giordano bivouac in the Mont-Rose massif, I met the president of the Romanian Alpine Club, who had just climbed Everest, and to my great surprise he told me that in Pakistan, it was possible to climb an 8000-meter peak on a very reasonable budget, provided we were self-sufficient.

In the summer of 2021, at Moskvina Camp in Tajikistan, I asked Carlos, a Spaniard with fourteen 8000 summits to his name, which seemed to him to be “the best budget-probability ratio”, and he answered without hesitation: “el Broad Peak”. Internet research later confirmed his advice.

Then, as luck would have it, my guide friend Jerome Sullivan recommended an agency in Pakistan based in Skardu, at the gateway to Baltoro, and Eric Bonnem, founder of the French agency Expeditions Unlimited, offered me a partnership to help us organize the expedition, provide altitude equipment, personalized weather routing, safety and communication equipment.

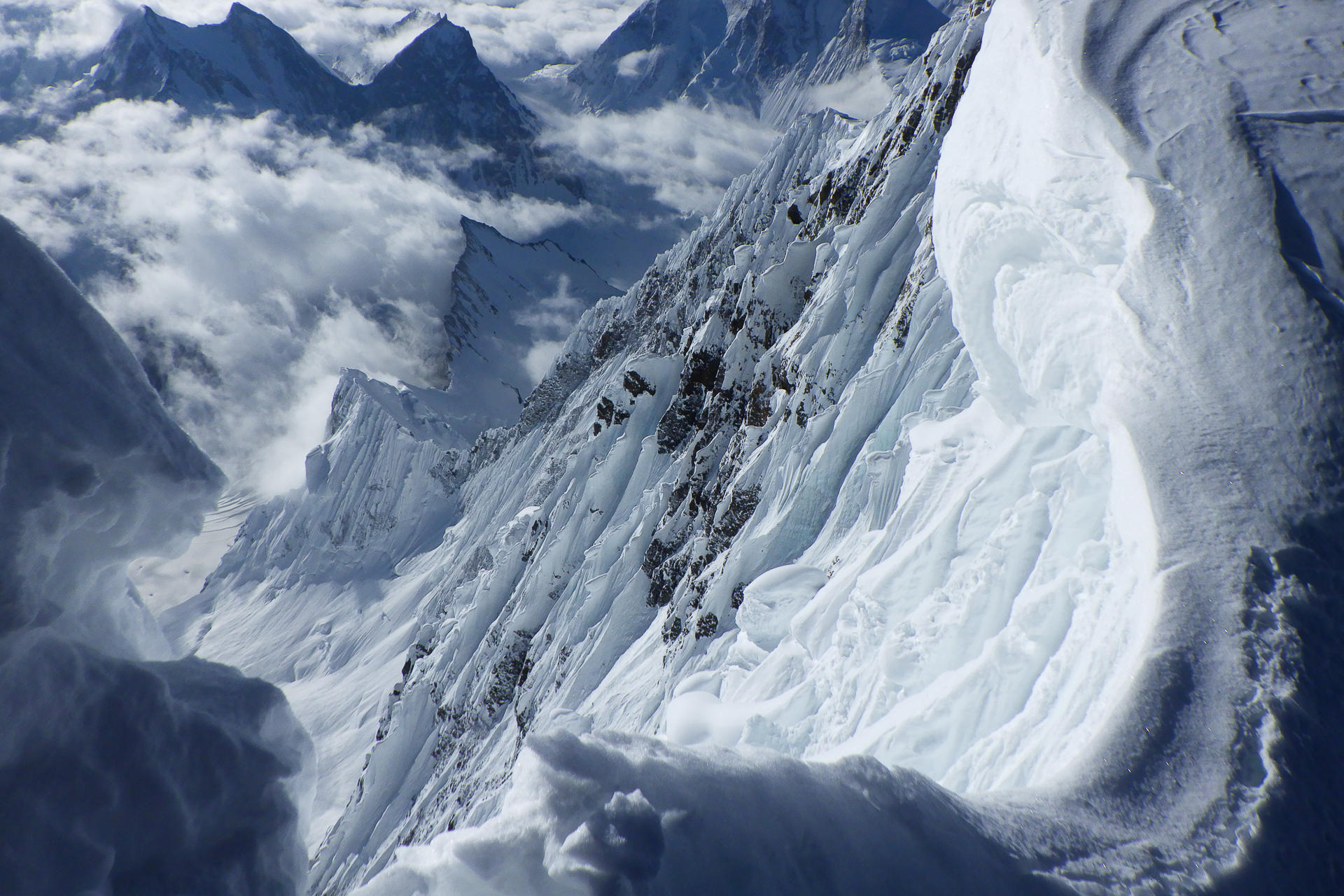

Viaw on Broad Peak © Jean-François Descat

Trekking approach thorugh the mythical Baltoro glacier

Thirty-three men and fifteen mules make their way up the Baltoro valley. Thirty of these men come from villages upstream: Askole, Jhola, Chobrok; from villages on the other side of the Gondoro Pass: Hushe and its surroundings; or from Skardu and its surrounding villages, such as the famous Sadpara. About twenty of them carry on their backs loads weighing thirty kilos, of more or less spectacular shapes: heaps of cans, rolls of floor mats, wooden crates... About ten guide their mules, loaded with a hundred kilos of tents, foodstuffs, tables and other folding chairs... Most of them are peasants practicing subsistence farming in isolated oases, sometimes even young students, earning the equivalent of 100 to 400 euros in ten to twelve days. They are filthy, shaggy, poorly shod, loud-mouthed, sleeping close together under tarpaulins stretched between piles of stones, with bruised backs and large blisters on their feet, one with a urinary tract infection, the other with an incessant dry cough, laughing loudly and singing joyfully in Balti dialect. Three of the men are Europeans on vacation: Julien and I, plus our Italian friend Lucas, whom we met at the foot of Korjenevskaya in 2022, and who decided to join us at the last minute.

Day after day, the Baltoro valley. Between two sunny spells, it gets grander and grander. The reliefs admired the day before and the days before remain visible, while new giants appear. Trango Tower, Cathedral, Lobsang and their immense walls and towers of ochre granite; Masherbrum, Chogolisa, Gasherbrum IV and its “shining wall”, giants of rock, snow and ice adorned in solar hues; in the distance, and still unreal, the intimidating Broad Peak and K2 reveal themselves between the clouds.

The crucial issue is managing hypoxia. To this end, before landing in Pakistan, Julien and I spent two improbable weeks in the Mont-Rose massif, living in the high mountains in unguarded refuges between 3,000 and 4,600 meters. Then we climbed slowly up the glacial Baltoro valley, negotiating as many stages as possible, to arrive at base camp at 4800 metres, in a condition to withstand an oxygen level that was already down to 50%. Another challenge is to avoid falling ill: hand hygiene, vigilant eating and not letting the cold get the better of us. Hopefully, we'll soon be able to enter the “death zone” with as much vitality as possible. The rest is just walking and not too difficult mountaineering.

Not too far from Concordia © Pascal Denoël

First steps on Broad Peak, first rotations

Sunday, June 16, 2024

11 a.m.: the three of us stand on the narrow summit of Pastore Peak, at 6150 meters. The weather is radiant, and in a single glance we can see the masses of Broad Peak and K2 right in front of us. We've had to carry 15-20 kilo rucksacks, sometimes under the snow, while panting; we've had to weave between crevasses and seracs, endure diarrhea and headaches, but so far everything is going according to plan. Having arrived early in the season, we've now had the Baltoro all to ourselves for two weeks, and acclimatization is going well.

Civilization suddenly catches up with us in the form of the friendly Benjamin Védrines and Sébastien Montaz-Rosset, whom we invite to share our lunch in our picturesque mess tent decorated with plastic flowers and the Pakistani flag. Day after day, our isolated moraine at the end of the world is filled with dozens of mountaineers and trekkers, hundreds of porters and mules, and just as many colorful tents. From up there, at 6,000 or 7,000 meters, in the night and silence, under the stars and the Milky Way, you can see the lights of two villages stretching out: the base camps of Broad Peak and K2.

Wednesday, June 19

The weather is not yet good enough to spend a night up there, but Julien and I decide to drop off some gear (a tent and some food) at Broad Peak camp 1 (5700 m). We're the first this season to survey the flanks of the giant, and we're doing it the way we know how: following the contour lines, the lines of weakness, the easiest passages; playing at understanding the mountain. We do so largely under snow, but a clearing welcomes us to the narrow rocky platform that serves as Camp 1, and we can admire the enormous cloud-draped rock masses emerging from the vast glacial expanses streaked with black boulders.

Sunday, June 16

11 a.m.: the three of us stand on the narrow summit of Pastore Peak, at 6150 meters. The weather is radiant, and in a single glance we can see the masses of Broad Peak and K2 right in front of us. We've had to carry 15-20 kilo rucksacks, sometimes under the snow, while panting; we've had to weave between crevasses and seracs, endure diarrhea and headaches, but so far everything is going according to plan. Having arrived early in the season, we've now had the Baltoro all to ourselves for two weeks, and acclimatization is going well.

Civilization suddenly catches up with us in the form of the friendly Benjamin Védrines and Sébastien Montaz-Rosset, whom we invite to share our lunch in our picturesque mess tent decorated with plastic flowers and the Pakistani flag. Day after day, our isolated moraine at the end of the world is filled with dozens of mountaineers and trekkers, hundreds of porters and mules, and just as many colorful tents. From up there, at 6,000 or 7,000 meters, in the night and silence, under the stars and the Milky Way, you can see the lights of two villages stretching out: the base camps of Broad Peak and K2.

Wednesday, June 19

The weather is not yet good enough to spend a night up there, but Julien and I decide to drop off some gear (a tent and some food) at Broad Peak camp 1 (5700 m). We're the first this season to survey the flanks of the giant, and we're doing it the way we know how: following the contour lines, the lines of weakness, the easiest passages; playing at understanding the mountain. We do so largely under snow, but a clearing welcomes us to the narrow rocky platform that serves as Camp 1, and we can admire the enormous cloud-draped rock masses emerging from the vast glacial expanses streaked with black boulders.

Climb towards C1 © Jean-François Descat

Monday, June 24

We start our first “rotation”. The rules of the game have totally changed: no more elegant curves; the slicing up and down the mountain by fixed ropes has begun. We pull on our jumar on snow slopes ranging from 35 to 55 degrees, loaded down with bags that are too heavy. Julien finds the exercise exhausting and pointless. As for me, I'm fine with it, and I have to admit that the tractor-in-first-flight aspect suits me quite well. Lucas, who hasn't been in good form since Pastore Peak, and whom we've already outdistanced somewhat, signals halfway up that he's giving up. We learn on our return to base camp that he's been pissing blood because of a urinary tract infection.

Tuesday June 25

Although the Pakistani fixing team has already installed the fixed ropes up to camp 2 (6200 m), it's been snowing since then and Julien and I have to make the track, sometimes up to our knees. On these steep slopes, at this altitude, loaded down with heavy packs, it's exhausting. And we're delighted to be overtaken by three Americans on skis. We reach Camp 2, which for the moment is populated only by a few dead tents and a deposit of static rope rolls. Here, we pitch our tents on a scabrous rocky ridge, right on the edge of wide ledges plunging into the abyss. The landscape becomes more expansive, the horizon of light reveals itself further between the multitude of peaks, and the smoking K2 still dominates us with its colossal mass.

Wednesday June 26

As soon as I reach the first steep slope above Camp 2, I think about giving up. I'm up to my waist. But I'm counting on Julien's reinforcement and then the American commitment. And indeed, after two hard hours, the three rockets take the lead. However, at 6700 meters, it was general surrender under a threatening sky and in flaky gusts. As Julien and I retraced our steps, somewhat dispirited, one of the Americans started to ski down, triggering an avalanche. Running as fast as I could, I shouted to Julien to get out of the way of the slab collapsing in our direction. It passed him three meters away. We take refuge on the rocks and let the skiers pass, triggering another avalanche, which takes on a staggering scale, ripping some forty centimetres of snow from the mountain and uncovering living ice.

My companions give up, and I am now alone in this adventure

Thursday June 27

Broad Peak base camp. In the time we've been roped together, I've often read the fear and anxiety in his silences, in his dark blue eyes and under his black eyebrows. This morning, it's terror and panic that invade his bloodshot, purple-ringed eyes. Julien will never climb Broad Peak again.

Tuesday, July 2

At 6,500 meters, Lucas, huddled on the slope, his back rounded in an attempt to relieve the weight of his pack, says to me in a faint voice: “I am sorry, I stop”. And so I was alone. A week later, he'll be back in Italy. I continue as planned to the top of the dome, at 6650 meters. There's a small, half-filled terrace dug out of the snow, where someone has spent the night. I pitch my tent there in the gusts.

K2 from camp 3 of Broad Peak © Jean-François Descat

Wednesday, July 3

In the early morning, I climb very slowly up the steep slope overlooking the dome and leading to Camp 3. A steady wind envelops me in a spray of snow. This damn bag is too heavy. I now have to carry a tent designed for three people on my own. I take four small steps that sink twenty centimetres into the blown snow, try not to lose my breath, and start again. I aim for the next anchorage or the next knot in the fixed rope, and allow myself a break by slouching down towards the valley, my pack resting on the slope, hanging from my Jumar handle. At this rate, it takes me four hours to climb the 350 metres to the wide glacial plateau that forms Camp 3. And a further three hours to shovel out a terrace in the snow at 7,000 metres in the freezing wind, set up my tent firmly and arrange my belongings inside. The site I've chosen is in an unusual tent cemetery, facing the sun and K2. I spend a comfortable late afternoon there, but in the night a treacherous headache forces me to shoot myself up with paracetamol. I left the shelter at 6am in thermals blowing at 40 km/h, without having slept a wink, and reached base camp at 10am. It took me four hours, abseiling on the fixed ropes, to descend what had taken me four days to climb.

Monday, July 22

I stand on a large rock to watch the little blue dot disappear into the horizon for as long as possible. It's Clémence, preceded by Julien, Adèle and Harold. They're heading for Concordia, to cross the Gondogoro La and return to France. The plan was for me to go with them, but mountain conditions decided otherwise. Over the last two weeks, due to wind and heavy snow, the fixed ropes have not yet reached the pass and have stopped at 7500 metres, leaving the team exhausted. As for me, I spent two more nights at Camp 2 to make deposits, keep busy and maintain my acclimatization, but the mountain wouldn't let me go back up to Camp 3. However, hope has been revived in the last few days, as the weather forecasts predict a window between July 25 and 30. Many people, like me, have postponed their return flights, and everyone is getting ready for a final Summit Push.

Jean-François at the top of Broad Peak © Jean-François Descat

Summit Push... And summit!

Thursday, July 27

9:30 pm: I've already been climbing for two hours through the night up the endless slopes towards this pass perched at 7800 meters, which has been towering over me for the past two months. I'm going as fast as I can, averaging 100 mph, in the snow trench sloping between 30 and 55 degrees. The track forces me to take long strides, push on my thighs and pull on my jumar. From Camp 3 to the pass, I pass climbers coming down from the ascent they started the day before, so they've been walking for 24 hours, and some will take up to 30-35 hours to reach their tents at Camp 3. The latecomers are bloodless: One was dragged through the snow by her excited porter, while another, on the edge of the huge track equipped with the fixed rope, asked me with a hallucinated look how to get to camp 3... A good number of them did not reach the summit, and I would later realize that those who did were for the vast majority either mountain professionals, often without oxygen, or amateurs with oxygen, guide and porters. All of them had climbed the day before following the fixing team, i.e. 45 to 50 people. However, the team had recommended not to follow them but to wait until the following day, despite the much better weather overnight. Each group had its own strategy: for example, the less acclimatized had to stop at all the camps, forcing them to climb in bad weather and spend restless nights in gusts of wind; or some ambitious climbers wanted to reach the summit in one go from the base camp, ending in failure and exhaustion.

Summit of Broad Peak © Jean-François Descat

As for me, I follow the advice of the local guides and porters: climb directly to camp 2, sleep there, the next morning climb to camp 3 and nap there all afternoon, then attack the summit at nightfall. I'm not following the crowd, but the advice of Eric [Bonnem, Expeditions Unlimited] and the forecasts of weather router Dominique Hennequin, whom I trust. Knowing that this is my only and last chance to reach the summit, and seeing the state in which the previous day's contenders are descending, I decide to use the oxygen I had originally planned to take only in case of problems.

Summit of Broad Peak © Jean-François Descat

Friday, July 28

3:30 a.m.: I reach the ridgeline just above the col and at the foot of the “rocky summit”. At last I can see what Broad Peak hides from us: China, that infinite sea of clouds that shimmers with a golden glow on the horizon. As I make my way across the many, exhausting peaks of the very long summit ridge, between 7900 and 8050 metres, day breaks on both sides of the border, setting the giants of the Karakorum ablaze. The weather is clear, almost windless. Totally alone, a powerful dialogue is established between me and the mountain. The immensity and sumptuousness of our world reward my efforts beyond my wildest dreams.

Summit of Broad Peak © Jean-François Descat

For me, as for all mountain dwellers, these hard-won moments are treasures that nothing and no-one can take away from us.

Jean-François Descat

August 15, 2024

Climb Broad Peak at 8047 meters in Pakistan

Climb K2 at 8611 meters in Pakistan

Expeditions Unlimited blog

Expeditions Unlimited blog