By the end of 1956, ten of the fourteen 8,000+ summits had been climbed by himalayists. Three had succumbed to the brilliance of Austrian mountaineers. In 1953, the most famous of them, Hermann Buhl, climbed Nanga Parbat in an odyssey to which we shall return. In 1957, four summits remained to be climbed, including two in Pakistan: Gasherbrum I, or Hidden Peak (8,068 m) and Broad Peak (8,047 m). Forerunners of the alpine-style expeditions to come, four Austrian mountaineers, including Hermann Buhl, achieved a feat that went almost unnoticed at the time. With no base camp, no high-altitude Sherpas and no oxygen, it was a daring feat. But the success still had its dark side, with the sudden death of Hermann Buhl in an ill-fated attempt on Chogolisa (7,665 m). A look back at this little-known expedition.

Marcus Schmuck, the Sestogradist.

At the age of 32, Marcus Schmuck, born near Salzburg and an electrician by profession, is a very strong climber with several first ascents of the sixth degree to his credit in what was then known as the Eastern Alps. Mainly in the large limestone walls around Salzburg: the Kaisergebirge and the Karwendel. Also a keen traveller, in 1955 he had the opportunity to take part in an expedition to Spitzbergen, a destination that was not very popular at the time. Walter Frauenberger, one of the members of the Spitzbergen trip, had been Hermann Buhl's companion on Nanga Parbat. Schmuck began to dream of the Karakoram.

Marcus Schmuck, the initiator of the project © Fritz Wintersteller

Buhl, the hero of Nanga Parbat

Hermann Buhl, a native of Innsbruck, a climber who would now be described as a professional, a strong ‘rock climber’ from the outset (solo ascent of the north-east face of Piz Badile in 4 hours 30 minutes), is a mountain guide and sells mountaineering equipment. His exceptional success on Nanga Parbat in 1953 brought him fame in the German-speaking world on a par with that of Gaston Rébuffat or Lionel Terray in France. His legal wrangling with the expedition leader, Karl Herrligkoffer, whom he totally refused to obey (the latter had given the order to abandon the mountain), has not yet ended. At 33, he too dreams of the Karakoram, to which he would like to return.

Hermann Buhl, the hero of Nanga Parbat © Fritz Wintersteller

From dream to reality

In 1956, during a chance encounter in a refuge on the Kaisergebirge, Schmuck and Buhl met and began climbing together, developing a friendship and mutual admiration. Schmuck excelled on dihedrals and chimneys, Buhl on slabs. Their reputation: never letting themselves be distracted from their goal. Even forgetting to eat and drink, to concentrate on the route to be climbed.

Schmuck, a friendly climber, had no desire to embark on a heavy expedition and wanted to carry out a project with friends. The Austrian success of Gasherbrum II in May 1954 and, even more so, that of Herbert Tichy's small expedition to Cho Oyu in November of the same year had shown the way. It must be possible to tackle an 8,000-metre ascent without altitude carriers, without oxygen and without ‘laying siege’ (as we used to say in those days).

The Broad Peak attracted the two men: of the four 8,000 climbs unbeaten at the time, Shishapangma in Tibet was inaccessible, Dhaulagiri had been judged too difficult by Lionel Terray himself and Gasherbrum I, a few metres higher than Broad Peak, was isolated, deep in the Baltoro glacier. In the event of a (common) porters' strike, they would have great difficulty reaching the base camp.

To transpose the Alpine style to the Himalayas with the best chance of success, Broad Peak seemed the obvious choice.

Another reason may have played a part in their choice: in 1954, Karl Herrligkoffer, the leader of the Nanga Parbat, hated by Hermann Buhl, led a heavy expedition (12 members) to Broad Peak. Bad weather forced them to abandon at 7,200 metres. A victory on this summit would be a resounding revenge for Hermann Buhl.

Who will be the leader?

Seen by the Alpine establishment as an act of insubordination, Buhl's near mutiny on Nanga Parbat led to him being banned from the Alpenverein (the Austrian Alpine Club, which provided financial support for the expeditions). No funding if he was the expedition leader. To get round this opposition, Schmuck, president of the local section of the Alpenverein, was put in charge of operations. In spite of Buhl's undoubted experience. But the highly respected association provided almost a third of the total budget, and they couldn't afford not to. Buhl was deeply angered by this decision, which he considered to be unjustified, and this reflected on his behaviour during the expedition.

And four more

With sufficient funds raised, the team added a third member, Fritz Wintersteller, Schmuck's companion in Spitsbergen. Three years younger (aged 30), an excellent climber, renowned for his calmness in all situations, his strength (he was nicknamed ‘the bull’) and his unfailing endurance made him an ideal partner.

Fritz Wintersteller, the indomitable © Marcus Schmuck

Buhl would also like to be accompanied by a doctor. There was no doctor on Nanga Parbat, where Buhl lost the big toe and half of another toe on his right foot. Schmuck, for his part, is only interested in alpine skills. Kurt Maix, president of the Viennese section of the Alpenverein and a fervent admirer of a brilliant young glaciarist, 25-year-old Kurt Diemberger, imposed him as his fourth partner. He was also supposed to act as... a doctor! The first three already knew and liked each other, but Diemberger was a complete stranger to them.

Kurt Diemberger, the youngest © Fritz Wintersteller

On the road

On 18 April 1954, accompanied by 65 porters, they set off for Baltoro. The food (chicken, eggs and chapatis) made them uncomfortable. Buhl, in particular, suffered from intestinal problems that weakened him. The usual problems arise: they haven't provided enough sunglasses or blankets for the porters. This led to tension between Schmuck, the official leader, and Buhl, the man on the ground. Wintersteller made the trail almost daily, while Diemberger let himself be carried along. When they reached Concordia, the porters refused to continue. They would have to carry 1,200 kilos of equipment themselves to the base camp 20 kilometres away. There were seven of them: four climbers, the liaison officer Qader Saeed, and two porters who agreed to stay. Three exhausting days in fresh snow (the weather was miserable), with packs weighing over thirty kilos each. Base camp on 9 May at 5,000 metres.

The ascent

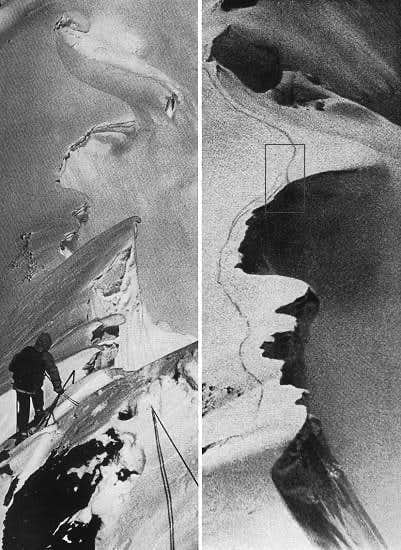

On 13 May, the four Austrians set off to set up camp 1. A 150-metre-high couloir, two metres wide and sloping at almost 50°, took them to 5,400 metres. Beyond that, the slope diminishes and at 5,800 metres, on a spur at the foot of a characteristic rock tooth, they set up camp 1. They returned to the glacier in a quick 20-minute slide on their backsides (they used this technique a lot between camps). Here, a snowfall stopped them in their tracks for two days.

Camp 1 (5,800 m) with its characteristic rock tooth © Wintersteller

From 16 to 19 May, they had to work hard in fresh snow, sometimes up to their thighs, to climb the 45 to 50° slopes that took them below a ledge where they could set up camp 2, at 6,450m. The rucksacks were heavy, and Wintersteller and Schmuck did most of the tracking. Buhl, whose intestinal problems had not yet been cured, was far from at his best. The weight of the bags to be carried quickly became a bone of contention, especially between Diemberger and Wintersteller. Wintersteller lived up to his reputation as a ‘bull’. Placid, as long as he wasn't annoyed, he ploughed on, unperturbed, whatever the conditions.

Camp 2 (6,450 m) in the shelter of the cornice © Wintersteller

On 20 May, they all left camp 1, with Schmuck and Diemberger descending to camp 2. On the plateau after camp 2, Buhl and Wintersteller came across a former Herrligkoffer depot: ropes, a tent and food: salami, bacon and an egg liqueur. Diemberger: ‘Perfectly preserved food in the highest freezer in the world’.

On 21 May, Buhl and Diemberger push a peak to 6,700 meters, but bad weather arrives. Everyone returned to base camp. They stayed there until the evening of the 25th, in an increasingly tense atmosphere.

On 26 May, they climbed back up to camp 2, which was buried under a metre of snow. On the 27th and 28th, Schmuck and Wintersteller were still toiling under heavy loads, while Diemberger and Buhl climbed to the Broad Col (Windy Gap) using Herrligkoffer's old fixed ropes. But it was still Wintersteller who reached the life-saving platform on which to set up the third and final camp at 7,100 meters.

First try

On 29 May, there were still 900 meters to climb to the summit. It was terribly cold, -25C° or -30°. Buhl was suffering from his right foot, which had been partially amputated after Nanga Parbat. Wintersteller, indestructible, was virtually alone on the trail. At the foot of the Windy Gap, a gaping crevasse blocked the way. Diemberger, the brilliant glaciarist, hesitated. Wintersteller crossed it, definitively establishing himself as the man in the lead. Higher up, below the col, at 7,800 meters, a sharp rise in mixed and hard ice forced him to cut steps and install 20 meters of fixed rope to allow the others to climb. Finally, they reached the Windy Gap or Broad Col at 7,900 meters. It's late, 4pm, maybe 5pm.

Schmuck is waiting for Buhl. Despite the late hour, he wants to finish the climb with his climbing partner. He lets Wintersteller and Diemberger continue in the lead. Buhl follows with sheer determination. At 8,000 meters, Schmuck and Buhl see Wintersteller and Diemberger standing 50 meters higher on what could be the summit. The clouds surround them and they can't determine whether or not they are on the summit. It was 6 p.m. and the rucksacks with the bivouac gear had been left under the Windy Gap: they would have to come back. It was an arduous return to camp 3, which we reached in the dark of night.

The next day, Schmuck and Wintersteller descend to base camp. Buhl, exhausted, and Diemberger even more so, took two days to descend. The bad weather set in again.

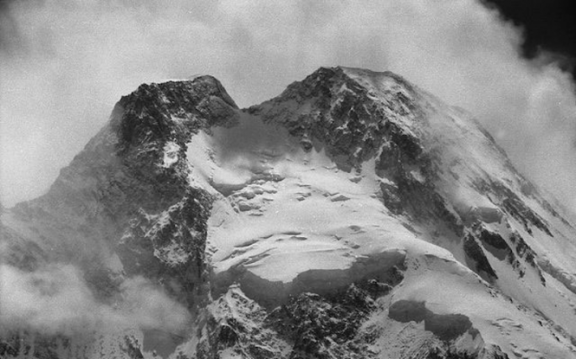

The long summit ridge between the antecima (8,028 m) and the summit (8,047 m) © alanarnette

The long summit ridge between the antecima (8,028 m) and the summit (8,047 m) © alanarnette

The second is the right one

7 June. As always, Wintersteller leads the way: camp 1, camp 2, camp 3...

On 9 June 1957, an overexcited Wintersteller reached the Windy Gap at 1pm. He waited for Schmuck and the pair set off again. By 4pm, they were standing on the antecap. On a clear day, the summit lies 400 metres further on, at the end of a long, gently sloping ridge. 5pm: Schmuck and Wintersteller have fulfilled their dream. Broad Peak, at 8,047 metres, has been climbed using alpine techniques. Despite the lack of supplementary oxygen, they stayed on the summit for an hour. Wintersteller, equipped with two Leica cameras that he had been carrying with him since the start of the expedition, shot away.

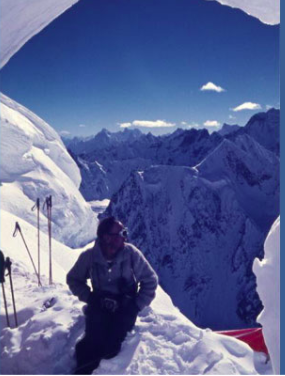

9 June 1957, 5pm. Marcus Schmuck at the summit of Broad Peak (8,047 m) © Fritz Wintersteller

Having reached Windy Gap, Buhl, at the limit of his strength, let Diemberger set off for the summit. At 6pm, Diemberger met Schmuck and Wintersteller, who were beginning to descend. He climbed to the summit, stayed a few minutes and then set off again. On the ridge, he met Buhl who, true to his reputation, was climbing stubbornly alone. There was no question of giving up. Diemberger set off for the summit with him. At 7pm, he took the iconic photo of Buhl at the summit of Broad Peak, the first mountaineer to have climbed two peaks over 8,000 meters. In the distance, Nanga Parbat, an image dear to Buhl, shines with its last light.

Hermann Buhl at the summit of Broad Peak.

On the left, the GIV pyramid and Nanga Parbat in the background © Kurt Diemberger

The full moon allowed them to descend to camp 3, which they reached at one o'clock in the morning, totally dehydrated.

Back at the base camp, the following days marked the definitive break between Schmuck and Wintersteller on the one hand, and Diemberger and Buhl on the other. The first two had brought down all their equipment from the high-altitude camps. The latter had to go back up to camps 2 and 3 to bring down theirs (tent, mattress, duvet...).

Schmuck and Wintersteller soon recovered from their exertions, setting off on skis to explore the Savoia glacier and climb the then uncharted summit of Skil Brum (7,360 m). Buhl and Diemberger, furious at their success, decided to set off on their own in the direction of Chogolisa (7,665 m). The liaison officer was concerned, as this ascent of a known peak was illegal.

The tragedy

On 27 June 1957, stopped by bad weather at 7,300 meters, Buhl and Diemberger had to descend. They followed a heavily gnarled ridge. The clouds separated them. Suddenly, Diemberger realised that Buhl was no longer following. He has to face the facts: Buhl, fooled by the fog, has strayed off the track. The ledge had given way under his weight.

Collapsed, Diemberger returned to the base camp. The three himalayists, the liaison officer and the two faithful porters set off in search of Buhl. All in vain. The slope on which he had fallen, probably almost 900 meters, was a vast avalanche funnel. There was no chance of him surviving, and no chance of finding his body.

The last traces of Hermann Buhl, interrupted on the edge of the fatal ledge

Buhl died at the height of his fame and Diemberger, his companion on the difficult ascent of Broad Peak, became the guardian of the legend. For better or for worse. The fact remains that this ascent, led mainly by two discreet mountaineers, Marcus Schmuck and Fritz Wintersteller, was the first of its kind: no high altitude Sherpas, no oxygen, in just three camps. They succeeded in transposing their alpine technique to an 8,000 m ascent. The icing on the cake was that all four climbed to the summit. But Hermann Buhl's death overshadows this remarkable success.

Broad Peak, 8,051 or 8,047 meters

Broad Peak has a geographical peculiarity: it is the only 8000m peak whose official altitude is open to question. In 1926, the summit was credited with 8,047 m (26,400 ft). But some sites, notably British, indicate that the Duke of Spolete's expedition in 1929 measured a different altitude of 8,051 m (26,414 ft). The article published in 1930 in the Journal of the Royal Geographical Society makes no mention whatsoever of this supposed new measurement.

We will therefore stick with the most frequently quoted altitude of 8,047 meters.

We propose the ascent of Broad Peak, another superb objective for a first experience at eight thousand metres.

The ascent of Broad Peak (8,047 m) is of a slightly higher technical level than that of Gasherbrum II (8,034 m). It offers a number of advantages. The direct route to the summit eliminates the need to spend long periods in the high altitude camps. The route is free from the usual objective dangers: no unstable serac bars, no large avalanche-prone slopes. We'll be joining our expeditions to Gasherbrum, Broad Peak and K2 on the beautiful approach walk to Baltoro.

See below the animated itinerary for the ascent of Broad Peak with a breathtaking view of K2...

Text by Didier Mille.

Climb Broad Peak at 8047 meters in Pakistan

Climb K2 at 8611 meters in Pakistan

Expeditions Unlimited blog

Expeditions Unlimited blog