The Second World War temporarily postponed the conquest of the world's ninth highest peak, Nanga Parbat. At 8,126 meters, it continues to resist the efforts of Himalayan climbers. After the tragedies of 1934 and 1937, it wasn't until 1953 that Germany, licking its wounds, considered taking up the challenge again. The story of Nanga Parbat then revolved around an exceptional but controversial figure: Dr Karl Maria Herrligkoffer. The true impresario of Nanga Parbat, he was the mastermind behind all the German expeditions to the mountain. Three of them brought him fame, including the legendary expedition by Hermann Buhl in 1953 on the historic north face (Rakhiot).

This is the second part of our saga of Nanga Parbat, ‘the killer mountain’.

See all our climbs above 8,000 meters.

Dr Karl Maria Herrligkoffer, the real impresario, enters the scene

The man who was to become ‘The’ Doctor Karl Maria Herrligkoffer was 18 years old when the tragedy of 1937 occurred. Willy Merkl, the leader of the expedition, lost his life along with fifteen other mountaineers and Sherpas. The death of Willy, Karl's older half-brother, was to shape his entire life: of the eighteen German attempts on the Nanga, eight were led by Karl Maria Herrligkoffer. A modest mountaineer, he nevertheless dreamed of taking up the torch, first for his half-brother, then for Germany.

At 37, his ambition was taking shape. He may not be an accomplished mountaineer, but he is a true mountain impresario, with a knack for convincing and raising funds, as well as organising each project with an iron fist. The British, his long-standing competitors, have nicknamed him ‘Sterling Case’. An ironic pun on his name, Herrligkoffer translates as ‘marvellous suitcase’!

.jpeg)

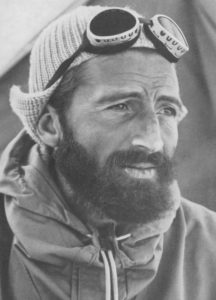

Dr Karl Maria Herrligkoffer, impresario of the Nanga Parbat © Maerz Muenchen

The mountaineers ‘invited’ on his expeditions had to sign a draconian contract: nothing was to be written about their actions, and Herrligkoffer reserved all publication and related rights for himself. This contract led to numerous legal disputes. All the more so as he ran everything from the base camps, often ignoring the reality of the higher camps. His conception of management did not sit well with the often highly individualistic spirit of the great Himalayan climbers. Herrligkoffer: ‘If I had to choose between the two, I would always choose the collaborative expedition, even if it didn't reach the summit.

A man unknown in mountaineering circles

The year 1953. Despite the peremptory judgement of Paul Bauer (1), ‘a man unknown in mountaineering circles and with no experience of the subject’, Dr Karl Maria Herrligkoffer, at the head of his foundation for the ‘Remembrance of Willy Merkl’, succeeded in raising the necessary funds for a major expedition. Many climbers could not resist the call of the Nanga and the prestigious heroes who had died on its flanks. He selected eight of them, including 29-year-old Hermann Buhl, already legendary for his successes in the Alps. In 1952, he made a breathtaking solo ascent of the north-east face of Piz Badile (3,308 m). Renowned for his stamina and his ability to forget everything, even eating and drinking, in order to devote himself solely to the summit, his individualistic spirit suggested that he might clash with Herrligkoffer's ‘collaborative’ approach.

Piz Badile, Cassin route, 1,000 meters of climbing, route still rated VI today © camptocamp.org

Mutiny at 6,500 meters

On 24 May 1953, the whole team was at base camp, at the foot of the now classic North Face and the Rakhiot glacier. The usual ballet between camps, interrupted by bad weather, enabled them to set up camp IV at the foot of the North Face of Rakhiot (6,700 m) on 24 June. The East Ridge, witness to the tragedy of 1934, had not even been reached yet, although the monsoon was forecast. On 30 June, Herrligkoffer ordered a retreat from the base camp. The four lead climbers decided to ignore the order. 1st July, the weather was fine, Herrligkoffer got angry... ‘Whatever! Buhl, Frauenberger, Ertl and Kempter literally mutinied. They climbed until they reached the East ridge, where they set up a precarious V camp (6,950 m). Too small for four people, Frauenberger and Ertl made their way back down to camp IV. Buhl and Kempter remained.

Hermann Buhl before Nanga Parbat © Hans Ertl, ZADA

On the road to glory

3 July 1953, 2am, bright and sunny. Buhl set off for the summit, Kempter following an hour later with bacon in his rucksack. Frauenberger and Ertl stayed behind at Camp V to help them on the way back. Silver Saddle (7,450 m), Diamir Breach (7,830 m). Kempter, far behind, gives up. Buhl has a thought for the bacon. All he took with him was some chocolate and dried fruit. Around midday, in the scorching heat, he dragged himself across the long plateau leading to the antecima (7,910 m), and dropped his rucksack to continue as lightly as possible. An ice axe, a pair of ski poles, a spare pair of mittens, the flag for the summit, a small water bottle, a few tablets of Pervitin... Onwards to glory.

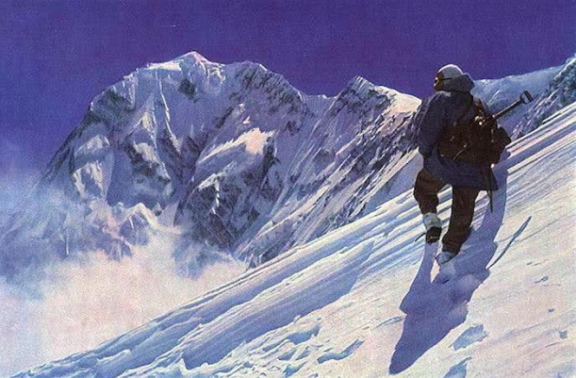

Storm on Nanga Parbat © Maerz Muenchen

Terra Incognitae

From the antecima, you have to descend a hundred meters to reach the depression known as the Bazhin Gap (7,812 m). 14 hours. Three hundred and fourteen metres of ascent and a thousand metres of ascent still separate it from the summit. A long, tapering ridge awaits. Anything but a leisurely stroll. Already tricky for a two-man rope party, even with oxygen. Buhl didn't hesitate to tackle it, alone and without oxygen! Without the slightest idea of the difficulties that awaited him. Here in Terre Inconnue, no-one has ever come this far before. Tiredness sets in. Two tablets of Pervitin revitalised him. The last obstacle before the summit was a granite gendarme blocking the way. A delicate traverse on small handholds, above a sidereal void.

3 July 1953, 6pm. One last shoulder (8,070 m), a few meters on all fours, Hermann Buhl stood up... ‘I didn't feel like a conquistador. I didn't feel like a conqueror, I was just happy to be done with the ordeal". He had just achieved the ultimate feat: climbing a virgin summit over eight thousand metres high, alone and without oxygen. As proof of his achievement, he left his ice axe at the summit.

The return odyssey

All that remains is to get back alive to talk about it. 7pm, night falls. Miraculously, the weather remained almost supernaturally calm, with a temperature close to zero. The descent began, and it was truly amazing. No headlamp, no ice axe, just ski poles. Suddenly, there was a strange sensation in his right foot: his crampon had just come off. He barely managed to catch it, but the strap went into the air. He hobbled along, clinging to the rock and reaching a tiny platform. There was no place to sit, it was pitch black. He waits for dawn, standing and holding on to the rock with one hand. The Buhl myth takes shape in these few gruelling hours of waiting, with no water and only a pullover and windbreaker for protection. His warmest and heaviest clothes remained in his rucksack.

The rest is a testament to the man himself. Nothing could stop his determination: he wanted to live. When dawn broke, he had barely dozed off for a few moments. His crampon, fixed as best he could with the cord from his over-pants, required him to kneel down frequently to fix it. An exhausting effort. Tortured by thirst and hunger, he hallucinated, saw a companion following him and advising him, lost his gloves... The spare pair hidden in his clothes saved him from the fate of Maurice Herzog on Annapurna. He wandered around the plateau where his bag had remained: should he go up? Or down? Miracle, he finds it. Inside was the all-powerful Pervitin: three more pills gave him the energy he needed to get to the tent in camp V, where Frauenberger and Ertl, who had come up from camp IV to meet him, feared the worst. It was hard to hide their emotion when they finally embraced.

Hermann Buhl photographed by Hans Ertl on 5 July 1953, returning to Camp V. © Hans Ertl

Herrligkoffer: how did it go?

Buhl suffered severe frostbite to his feet. The rest of the descent on 5 July was a real ordeal. On arrival at the base camp, Herrligkoffer's icy welcome was greeted with a terse ‘Well, how did it go?’ and later ‘How are you feeling? Herrligkoffer took Buhl's solitary success very badly, as it undermined his leadership.

In a twist of fate, the Germans who had paid so much for this victory were robbed of it by an Austrian. Buhl had carried the Pakistani banner and that of his Innsbruck club. No German flag. This contributed to souring relations with Herrligkoffer.

Hermann Buhl could have adopted the famous phrase of Henri Guillaumet (2), the survivor of the Andes: ‘What I did, no beast would have done’.

The hidden face of Hermann Buhl

The time has come to tackle a delicate subject: the use of Pervitin (3). During a film shoot, Hermann Buhl had an unfortunate fall into a crevasse. His shoulder was injured and he was shocked. The film crew made him swallow two pills, the use of which he didn't seem to know. Buhl: ‘The pills had a magical effect and I suddenly felt as if nothing had happened. On the slopes of Nanga Parbat, he swallowed two pills on the way up and three on the way down. The state of hypnosis he refers to is easier to explain... But mountaineers don't take drugs, as we all know!

Climb Nanga Parbat at 8126 meters in Pakistan.

Kurt Diemberger in the early 50s. The guardian of the Hermann Buhl myth

Text by Didier Mille.

____

(1) Paul Bauer, experienced mountaineer, leader of the 1929 and 1931 German expeditions to Kangchenjunga, responsible for search operations on Nanga Parbat during the 1937 tragedy.

(2) Henri Guillaumet, an airmail pilot, made a forced landing in the Andes in 1930. To survive, he had to crawl dozens of kilometres to reach the lower valleys. See Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's fine book Terre des Hommes.

(3) Pervitin is a derivative of methamphetamine, widely known as the ‘combat drug’ of the German army during the Second World War. Highly addictive, it prevents sleep. More than a doping agent, it is a drug.

Climb Nanga Parbat at 8126 meters in Pakistan

Climb Broad Peak at 8047 meters in Pakistan

Expeditions Unlimited blog

Expeditions Unlimited blog