Among the ‘Seven Summits’, the seven highest peaks on the continents, Mount Kilimanjaro occupies a special place: Hans Meyer, a man of science rather than a mountaineer, climbed it for the first time in 1889. Above all, he did it for the honour of his country and its Emperor: the Germany of Frederick William II. This first ascent remains unknown to the French. And with good reason, as Bismarck's Germany was our sworn enemy at the time, there was no question of highlighting this masterly achievement.

See all the climbs of the Seven Summits challenge.

1871: The German Empire is born

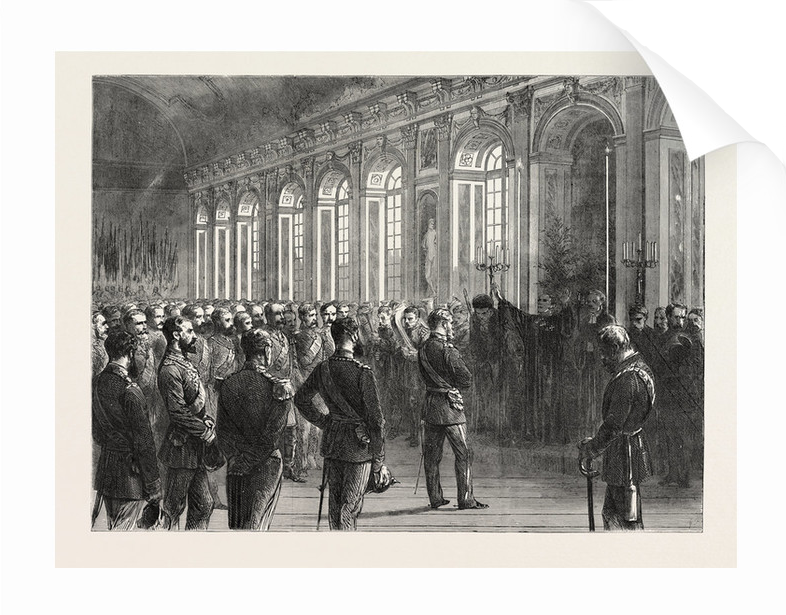

On 18 January 1871, in the Hall of Mirrors at the Château de Versailles, King William I of Prussia, victorious over Napoleon III's armies, was proclaimed ‘German Emperor’ and established a new nation state, the German Empire. The colonial era was in full swing. In Africa, the land of opportunity, England and France took the lion's share. The young German Empire was constantly competing with them.

1871, the proclamation of the German Emperor in the Hall of Mirrors at the Château de Versailles

© Magnolia box

From eternal snow to the equator

Missionaries, the first architects of colonialism, have been scouring Africa since the middle of the 19th century, hoping to halt the advance of Islam. As early as 1848, two German pastors, Ludwig Krapf and Johannes Rebmann, reported that they had seen a sparkling mountain in the plains to the north of the Sultanate of Zanzibar, known locally as Kilimansharo. The name stuck.

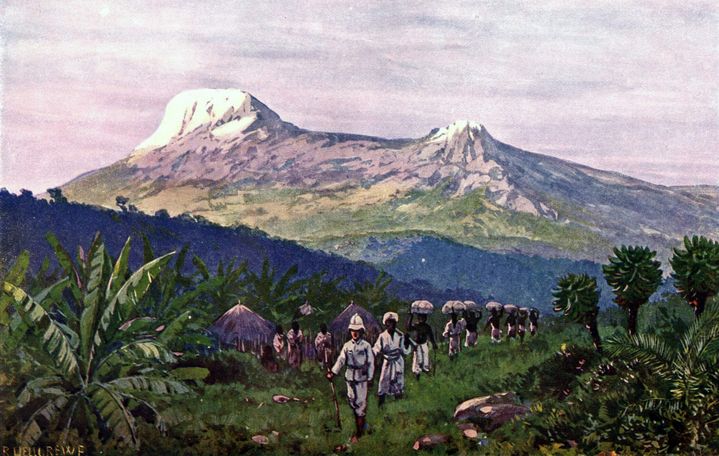

The caravan of pastors Krapf and Rebmann on the plains at the foot of Kilimanjaro

© Église évangélique du Württemberg

A few months later, in 1849, Rebmann approached the mountain and found that the summit was in fact covered in glaciers. The news was greeted with scepticism by the international community: snow at the equator? For the Royal Geographical Society, it's impossible. And it's no secret that malaria is rife on these plains, causing hallucinations! To corroborate Rebmann's claims, Krapf also reported, at the end of December 1849, the presence of eternal snow at the summit of Mount Kibo. Estimated altitude for what we now know to be an ancient volcano: 6,100 meters.

Tanganyika, ancestor of Tanzania

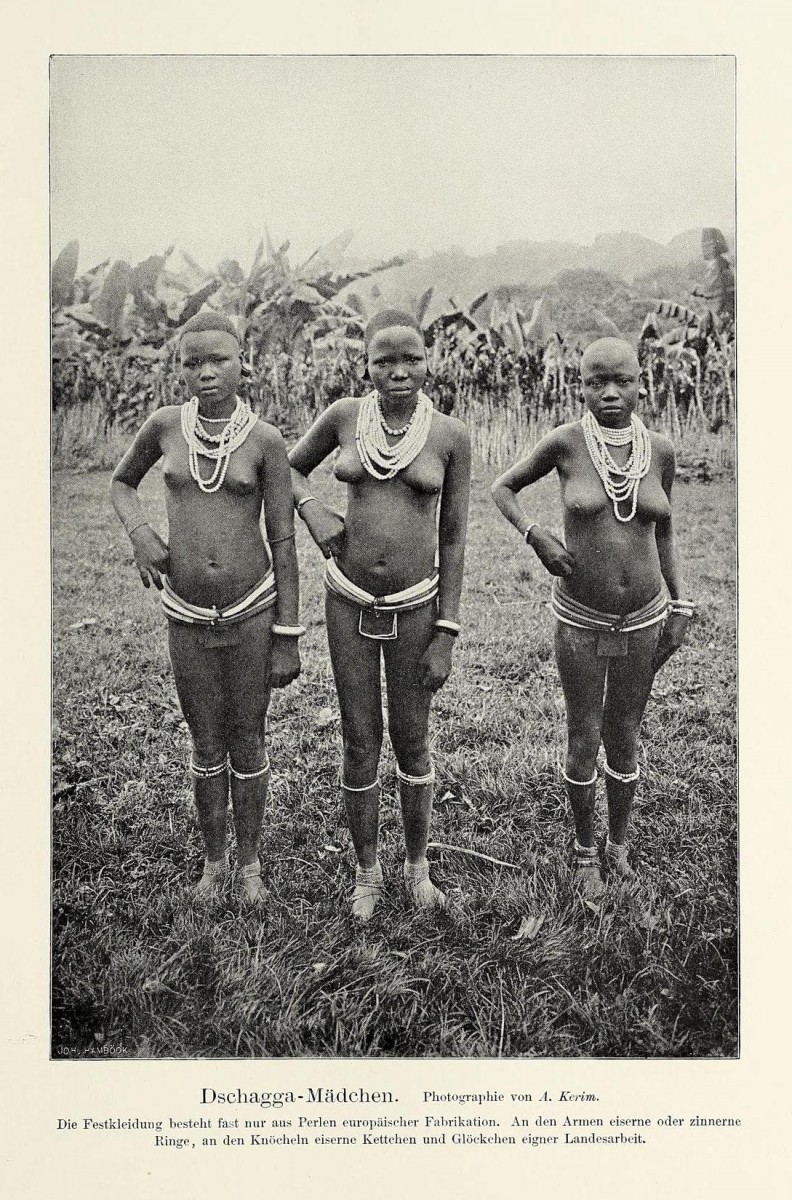

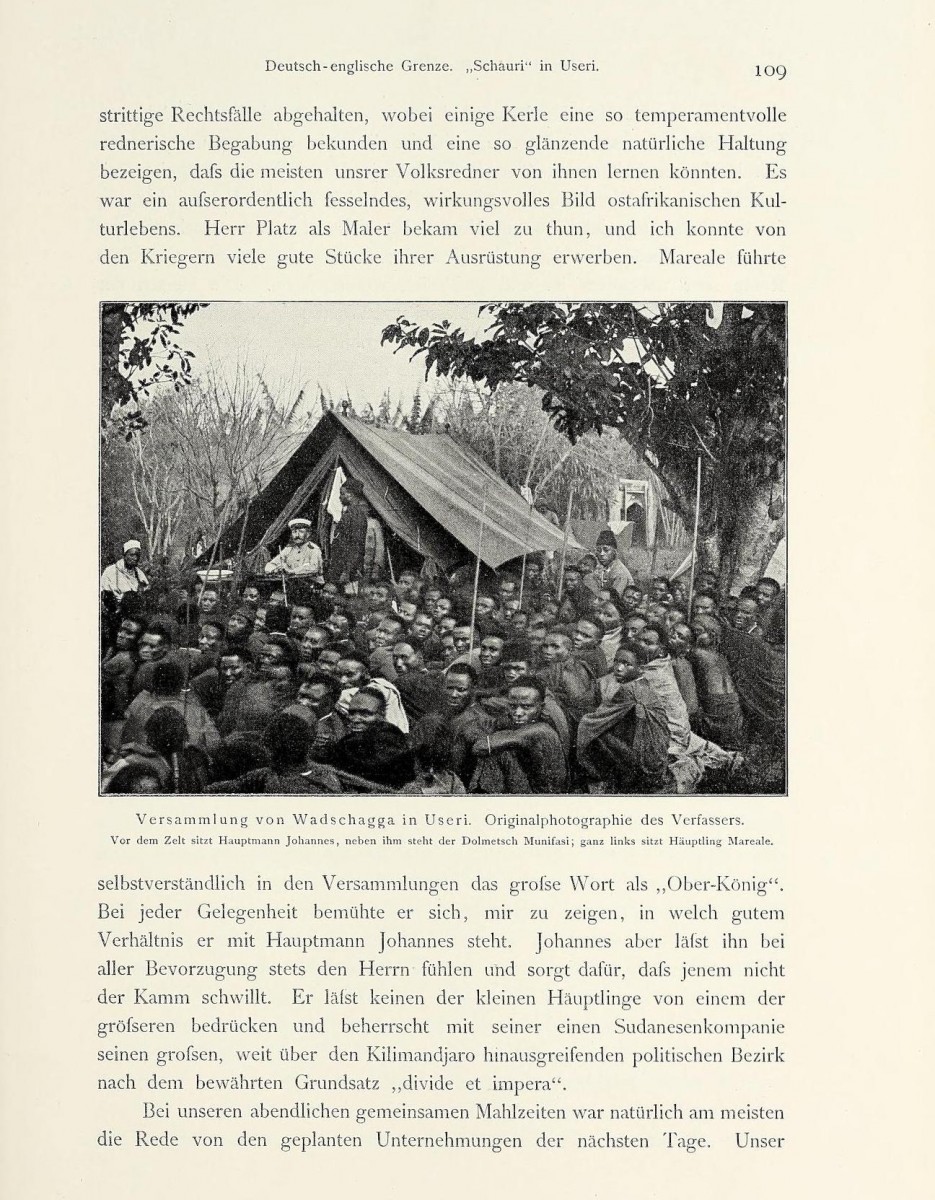

At a time of fierce colonial competition, against a backdrop of the fight against the black slave trade, a sordid business whose mastermind was none other than the paramount ruler of Zanzibar, the German and British Empires reached an agreement to the detriment of the Sultan. Bismarck's dispatch in August 1885 of five warships to aim their cannons at the walls of Zanzibar was a powerful argument. To the British, Kenya and its mountains. To the Germans, Tanganyika with Mount Kibo, named after the Jagga tribe who live at its foot.

Young Jagga girls at the foot of Kilimanjaro © Hans Meyer

Snowstorm at the equator, a real children's tale

In 1862, Baron von der Decken climbed the mountain. He too estimated the final altitude at almost 6,000 metres. At 4,300 metres, a snowstorm interrupted the ascent. On his return, Decken was strongly attacked by an Irish geographer, Mr Desborough Cooley. So the Baron says that it snowed during the night,’ he exclaimed. In December, with the sun in the sky! (...) This description of a snowstorm at the equator during the hottest season of the year, and at an altitude of barely four thousand meters, is all too obviously a children's story.

But he was wrong. Finally convinced, the Royal Geographical Society put an end to the controversy by awarding the Baron its prestigious gold medal. And if ridicule killed, Cooley would not have survived!

For Hans Meyer, reaching the summit of Kilimanjaro is a national duty

Hans Meyer, a young German scientist with a passion for geography and geology, set out to conquer Kilimanjaro. In 1887, at the age of 29, he had already made an impressive number of trips: to the Himalayas, South India, Ceylon, Java, the Philippines, China, Japan, Mexico and California. Attracted by East Africa, he is particularly keen to climb Kilimanjaro. Meyer: Kilimanjaro was discovered by a German, the missionary Rebmann; it was first explored by a German - Baron von der Decken; and it seemed to me almost a national duty that a German should be the first to set foot on the summit of this mountain, probably the highest in Africa, and certainly the highest in the German Empire. This first attempt, made from the village of Marangu on the south-eastern slope, led him to the vast plateau that separates Mount Mawenzi (5,148 m) from Kibo. At 5,500 metres of altitude, he came up against the imposing ice cap covering the summit of the latter. Without mountaineering equipment, he had to give up.

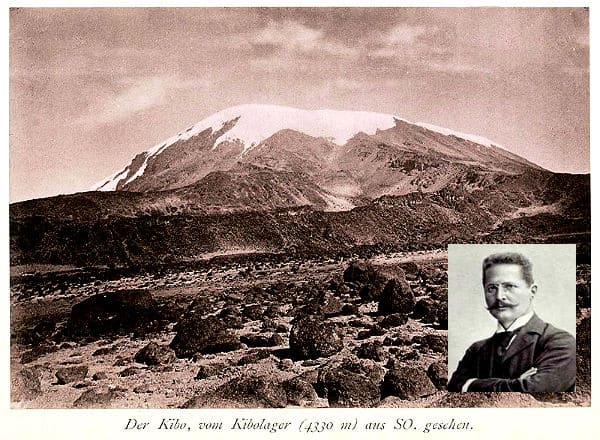

Hans Meyer, German geographer and geologist, the first to reach the summit of Mount Kilimanjaro.

The imposing summit ice cap is clearly visible © Kilimandjaro Wiki

The second expedition turns into a rout

As soon as he returned to Europe, he mounted a second expedition. In July 1888, he left Zanzibar accompanied by 230 porters. Having got ahead of his porters, he realised that they had turned back on the orders of the Sultan of Zanzibar, who was trying to quell a revolt.

An uprising had broken out on the coast against the East German African Company. After a series of twists and turns, Meyers and his companion are finally taken prisoner by the rebels, and only the payment of a large ransom will enable them to escape a worse fate. Back to square one.

Hiring porters: a time of intense negotiation © Hans Meyer

Otto Ehlers claims to have conquered the summit

That same year, another German national tried his luck on the slopes of Kilimanjaro: Otto Ehlers, a representative of the East German African Society. On his return, Ehlers published a colourful account boasting that he had reached the summit. There was no trace of a crater,’ he wrote, ’and the ice formed a series of gentle undulations covered by a layer of freshly fallen snow. The altitude reached could not have been less than 6,000 meters. His word was soon challenged and he finally admitted his guilt.

Third time's a charm

Not an active member of the German Alpine Club, Hans Meyer naturally heard about the famous alpinists of the time, including a certain Ludwig Purtscheller. Purtscheller, an Austrian and a top-class mountaineer, won Meyers‘ good graces by proving that Otto Ehlers’ story was totally fanciful. He offered to accompany Meyers on his next expedition. The offer was immediately accepted.

Suddenly, a vast crater opens up beneath their feet

This time, luck smiled on him. On 3 October 1889, they finally reached the foot of the ice cap, facing a slope of ice (and not snow as they had hoped), inclined at 35° and estimated to be 60 meters thick. Meyers: ‘At 10.30am, after an enthusiastic “Onward!”, the hard work of cutting steps in ice as hard as glass begins. Each step requires about twenty ice axe strokes.’ Exhausting effort at this altitude.

While Purtscheller had a pair of crampons, Meyers had to make do with his studded boots. Nevertheless, they roped themselves up, for the illusion of safety. By 2pm, they were close to the summit. Meyers again: ‘We feverishly took the last few steps. At last, the secret of Kibo is revealed before us. At our feet, a gigantic, steep-sided crater opened up, occupying the entire summit of the mountain.' Otto Ehlers' alleged victory was nothing more than a pure fabrication.

But to their disappointment, the highest point of the mountain was on the other side of the crater, and would probably require another two hours of effort. Wisely, they headed back down, determined to return as soon as possible.

Kaiser Wilhelm Peak, the highest point in Africa and the German Empire

By 8.45am on 6 October, they were back on the rim of the crater. It took them two hours of exhausting walking in rarefied air to reach the base of the three teeth that form the summit. They climbed painfully between the scree that covered the sides of the three peaks.

Meyers again: [At the age of 31], I was the first to set foot on the highest point, reached at half past ten. Taking out a small German flag, which I had brought with me for the purpose, I planted it on the lava peak with three resounding cheers. By virtue of the right conferred on the first climber, I christened this highest point in Africa: Kaiser Wilhelm Point.

Ludwig Purtscheller is celebrating his fortieth birthday with this dazzling success.

Hans Meyer and Ludwig Purtscheller at the summit of Uhuru Peak (Kaiser Wilhem Spitze) © CMK

See the snows of Kilimanjaro, for how much longer?

The altitude was eventually corrected to 5,895 meters and, since the end of the colonial period, the summit has had a local name, Uhuru Peak.

Mount Mawenzi seen from the saddle separating it from Kibo © Hans Meyer

Climbing Kilimanjaro is an unforgettable experience. The view from the crater towards Mawenzi, surrounded by its sea of clouds, reminds us that we are standing on the roof of Africa.

But the account of Meyers and Purtscheller's ascent reminds us of the speed with which climate change is affecting tropical glaciers.

The current southern slope

The current southern slope

Below is an animation showing the ascent of Kilimanjaro:

Text and animation by Didier Mille.

Ascent of Kilimanjaro at 5895 meters Machame route

Climb Aconcagua at 6962 meters standard route in Argentina

Expeditions Unlimited blog

Expeditions Unlimited blog