At 5,642 meters, Mount Elbrus is the roof of Europe, and not our beloved Mont Blanc, as many people think. To complete the Seven Summits challenge, climbing Elbrus is a must. In this article, we look back at the origins of the ascent to the highest peak in the Caucasus and Europe. Given the current geopolitical situation, it goes without saying that the climb to mount Elbrus is currently on hold. However, we wanted to bring our saga on this remarkable challenge to a close.

See all the climbs of the Seven Summits challenge.

The Russian Academy of Sciences is born in Saint Petersburg

Founded in 1724 by Peter the Great, the Russian Academy of Sciences organized expeditions to learn more about the territories conquered by Tsarist Russia. In 1725, Peter the Great entrusted Danish explorer Vitus Bering with a vital mission: to see if it was possible to reach the American continent from the west. The success of this undertaking was a credit to the Académie des Sciences, which emerged glorified.

In 1813, Russian astronomer Vikenty Vishnevsky measured Elbrus: 5,648 meters for the western summit, 5,609 meters for the eastern. Astonishingly accurate for the means available at the time, the current measurements are 5,642 meters and 5,621 meters respectively. Vishevsky can be proud of having identified the highest point in the Caucasus.

Climbing Elbrus for the Tsar's honor

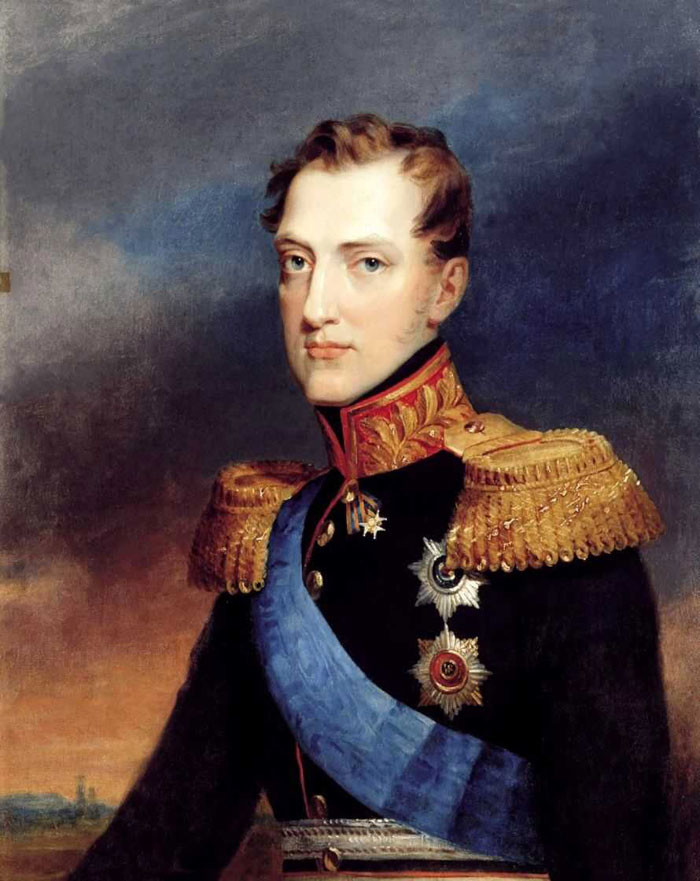

In 1828, war broke out between the Russian Empire, then led by Tsar Nicholas I, and the Ottoman Empire. It was not the first conflict with the southern neighbor, nor would it be the last. Most of the fighting took place in the Balkans. At the same time, General Georgi Emmanuel, Governor of the Caucasus, was battling the region's Muslim tribes with the aim of annexing their territories. The following year, in 1829, eager to explore Elbrus and, why not, climb it, he contacted the Russian Academy of Sciences, which assigned him four scientists. Among them was a Frenchman, Jean Charles de Besse, who would recount the adventure. The crew was large: “600 Russians and 400 Cossacks, which was a necessary safety measure in these wild countries.” [1]

The expedition settles at the foot of the North Face.

Nicolas the first, a warrior tsar on the throne

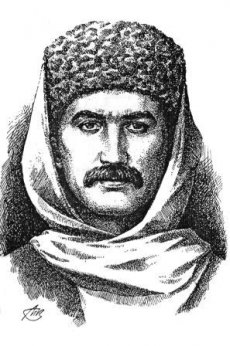

Khilar Khashirov “an ugly, lame man” pioneer of the Elbrus

On July 22, 1829, Khilar Khashirov, a Circassian (one of the peoples of the Caucasus) acting as local guide for Georgi Emmanuel's expedition, reached the “summit” around noon, climbed from the northern slope. General Emmanuel followed the progress through his telescope.

Besse: “After lunch, the general summoned the people who were to make up this little caravan, harangued them in the presence of the staff, and promised the one who would climb to the summit first one hundred silver rubles, fifty to the second, and thirty-five to the third.”

In 1829, the Magazine français des voyageurs et géographes published an account of the ascent:

“On the 22nd [July], they set off at three in the morning. Staying in camp, we followed their slow progress with keen interest. By nine o'clock in the morning, they had surmounted more than half the ascent. An hour later, a single person appeared above the rocks and headed for the summit of Elbrus with a determined step. In vain, we expected others to follow: no one appeared - on the contrary, many began to descend. Our eyes were focused on the only one to continue boldly. Resting every five or six steps, he bravely advanced, before disappearing into the rocks below the summit. At eleven o'clock, he suddenly appeared above Elbrus. When he returned, we realized that the winner was a Kabardian (Circassian) former shepherd named Khilar, an ugly, lame man. As a reward, he received the prize offered by General Emmanuel - 100 roubles in credits and five arshins of cloth.”

Khilar Khashirov, the pioneer at the summit of Elbrus © Mountain.ru

Summit climbed? Yes, but which one? It seems to be the eastern summit, the lowest. Perhaps the easiest to access from the north? Besse's report doesn't mention it.

No matter, the expedition proved a success, and General Georgi Emmanuel became a member of the prestigious Russian Academy of Sciences.

But for the mountaineers of the second half of the 19th century, mainly British, the highest summit of Elbrus, the Western one, remained to be climbed.

Douglas Freshfield climbs Mount Kazbek

In the summer of 1868, Douglas Freshfield, a 23-year-old Londoner, established his reputation as a skilled explorer and mountaineer by traversing the mountains of the Caucasus.

On July 1, 1868, the small team led by Freshfield claimed a major victory: Mount Kazbek (5,054 m) in the eastern Caucasus. They then headed for Elbrus.

Mount Kazbek, a magnificent Georgian pyramid © Dookinternational

Elbrus: presumed victory

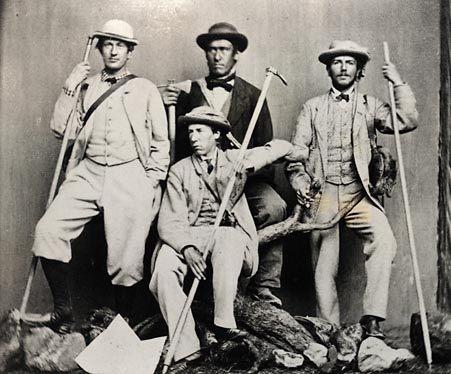

From his remarkable book, Travels in Central Caucasus, published in 1869, it appears that he and his five companions (Englishmen C. C. Tucker, A. W. Moore, Chamonix guide François Devouassoud and two local porters) reached the “summit” on July 31, 1868, after an ascent marked by Freshfield's fall into a crevasse, from which he narrowly escaped. They too made the ascent from the north face.

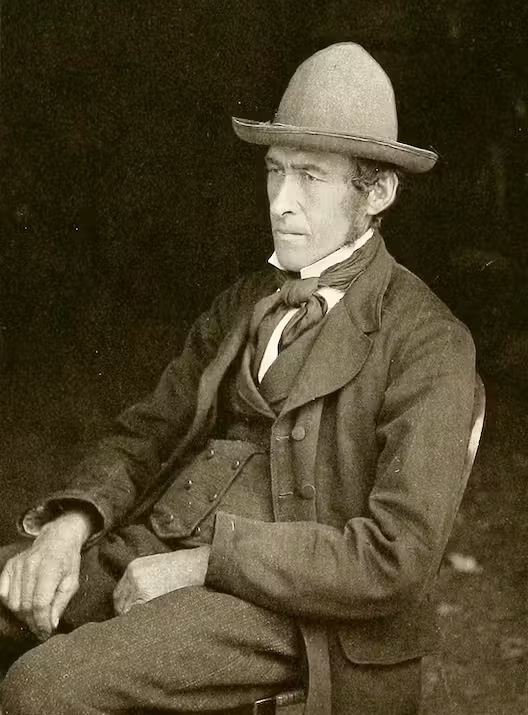

François Joseph Devouassoud: “François was a jolly fellow, bon vivant and strong as an ox” (Hervey Fisher).

Freshfield: “We reached the summit of Elbrus at 10.40am, and left a few minutes after 11am. We had some difficulty reconciling the appearance of the mountain summit, seen from a distance, either to the north or south, with its actual shape. From Poti [Georgian port on the Black Sea], Elbrus appears to culminate in two peaks of apparently equal height, separated by a considerable hollow. The gaps between the peaks we visited were no more than 150 feet deep, and we were surprised that they were so visible from a distance. Walking around the horseshoe ridge, we naturally looked to see if there was another peak, but none was visible; and to the west (where, if anything, it should have been), the slopes dipped to the west and there were no clouds dense enough to conceal an eminence almost equal in height to the one on which we stood.”

Douglas Freshfield in the middle

1874, the final victory goes to Grove and his companions

It wasn't until 1874 that this alleged victory was cleared up. British mountaineers Florence Crauford Grove, Frederick Gardner and Horace Walker, accompanied by Swiss guide Peter Knubel from the Valais, climbed Elbrus again, this time from the south face.

Grove: “The peak we climbed was not the same as the one climbed by Mr. Freshfield and his companions in 1868. [...] When we then compared our notes with those of Mr. Freshfield and Mr. Moore, they also came to the conclusion that the summit we were standing on was not the same as the one they had reached, and it may be considered certain that they climbed the eastern peak, we the western. [...] When we found ourselves on the western peak, the other appeared to be at the same level as ourselves, and I believe that careful observation would show that the two peaks are almost exactly equal in height. Until observations are made [...] the western summit must be assumed to be the higher.”

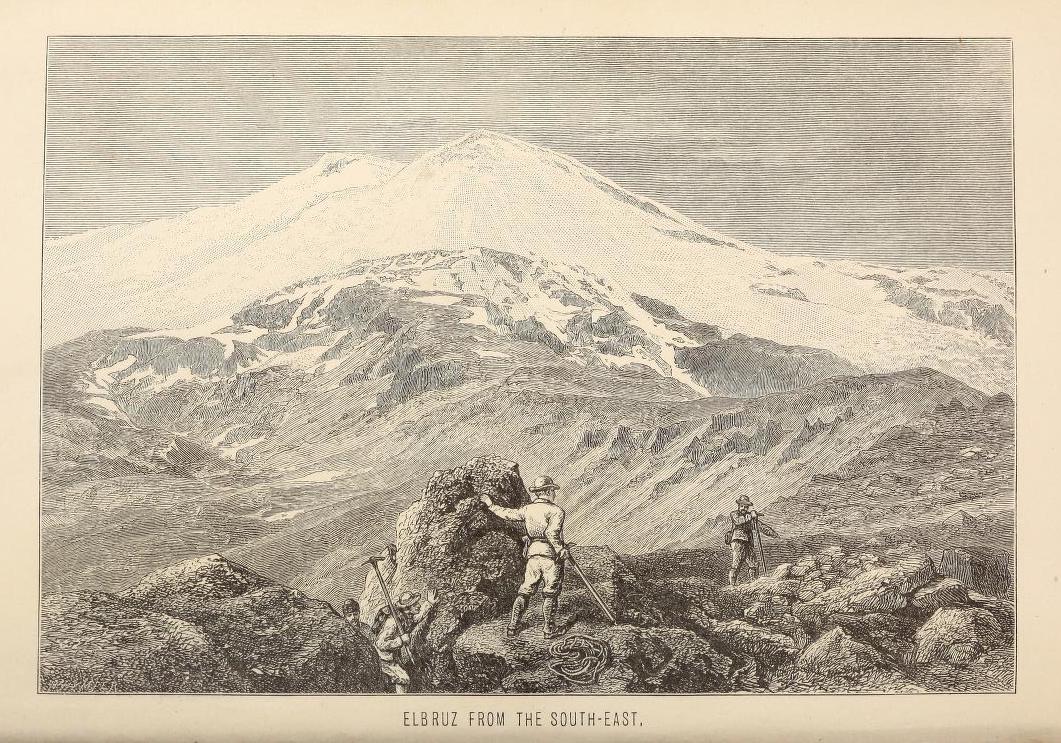

Elbrus seen from the southeast, engraving from Crauford Grove © The Frosty Caucasus - Grove

Elbrus seen from the southeast, engraving from Crauford Grove © The Frosty Caucasus - Grove

Today, the normal route of Elbrus takes place on the southern slope. The wilder, less-frequented north face retains some of its mystery.

From Elbrus to Kangchenjunga, the busy life of Douglas Freshfield

In 1899, Douglas Freshfield made a name for himself by completing the first complete tour of the Kangchenjunga massif on the Indo-Nepalese border. A very active member of the famous Royal Geographical Society and president of the no less famous Alpine Club, he was one of an extraordinary number of great travelers and mountaineers from across the Channel.

Text by Didier Mille.

Find out more about Climbing Elbrus at 5,642 m via the north face here.

[1] Bulletin des Sciences Géographiques, Economie Publique, Voyages. 1830. Tome XXI, p.497-501.

Climb Elbrus at 5642 meters in Russia

Ascent of Kilimanjaro at 5895 meters Machame route

Expeditions Unlimited blog

Expeditions Unlimited blog