“It's been seven days since we left base camp. This is our fifth bivouac since Camp I. There are no supplies and no water. There are no supplies, no possibility of making water: our bodies are deteriorating very quickly.” At an altitude of 6,500 meters of altitude, in the winter of 1954, the six young French climbers on the south face of Aconcagua were playing for their lives. They couldn't survive another bivouac. In the indifference typical of those years, when news still travelled slowly, a drama was unfolding up there, at the end of the world, on the edge of those austral lands honoured by another figure in mountaineering: the Swiss guide Matthias Zurbriggen, the winner of the Aconcagua. The roof of the Americas, a gentle summit for some, an icy inferno for others, attracts numerous contenders every year. And with good reason: it's one of the most accessible summits in the Seven Summits challenge. Accessible? Possibly. But that's without the fearsome wind, which often blows like a storm. Here's a look back at some of the most memorable ascents of the highest Andean peak.

See all the climbs of the Seven Summits challenge.

“Bold in conception, prudent in execution”.

This was the motto of Berlin-born Paul Güssfeldt, whose achievements include the first ascent of Mont Blanc's Aiguille Blanche de Peuterey in 1893. At the age of 53, this ascent marked the pinnacle of his alpine career.

An inveterate explorer, he made his first serious attempt on the slopes of Aconcagua, which he approached in February 1883. German settlers in Chile and muleteers living at the foot of the Andean giant helped him reach the foot of the mountain from Chile, following a very long approach. Given the violence of the wind, Güssfeldt and his three companions (simple muleteers) soon gave up the use of tents, contenting themselves with sleeping in the open air, loosely protected by the low walls that the Chileans masterfully constructed! Despite the lack of equipment to cope with the altitude, the total absence of maps and ignorance of the conditions around the summit, they made inexorable progress. Starting from a rough bivouac at 3,600 meters, they reached an altitude of 6,560 meters on the northwest ridge, not far from what would become the Independencia camp. Exhausted, they descend again. Their trek had taken a total of 31 hours, and they hadn't slept a wink! But they had paved the way for the future conquest.

Aconcagua in 1884 © Paul Güssfeldt

The FitzGerald Expedition

During his expeditions to the Himalayas, the famous British explorer Martin Conway hired his regular Swiss guide, Matthias Zurbriggen. In 1894, Conway invited British-born American mountaineer Edward FitzGerald to join him in the Karakoram. FitzGerald was very impressed by Zurbriggen's skills.

Edward FitzGerald, English-born American mountaineer

Two years later, FitzGerald decided to tackle Aconcagua, already recognized as the highest peak in the Americas. He naturally called on Matthias Zurbriggen. The road from Mendoza to the Chilean border had just been built. At the end of December 1896, the base camp was established at Puente del Inca, at the end of the Horcones valley. They first headed for the east face, then recognized access to the south face. They rightly judged it impossible to climb these slopes with the means at their disposal. They then considered the north-west face, where they would concentrate their efforts. They set up camp at the now famous Plaza de Mulas.

On December 31, as they ascended the slopes of the north-west face, at around 6,100 meters, Zurbriggen's feet became numb: his comrades struggled to restore circulation, massaging his feet with... brandy. Zurbriggen's guide also swallowed a good dose of brandy: we now know that alcohol is totally inadvisable in these situations.

Matthias Zurbriggen narrowly avoids drowning

On January 1, 1897, another attempt was made. This time, it was the scree slopes and strong winds that broke the men's resolve. Exhausted and hungry, they decided to return to Puente del Inca to regain their health. But as they crossed the Rio Horcones, Zurbriggen came close to a tragic end. Swept along with his mule by the tumultuous waters, he narrowly escaped drowning.

.jpeg)

Matthias Zurbriggen, from Matterhorn to Aconcagua, renowned Swiss guide © Alta Montanha

Victory for Zurbriggen, bitter disappointment for FitzGerald

On January 9, they set off again for the mountains. On January 12, they leave Plaza de Mulas. But FitzGerald had to give up at around 6,200 meters, suffering from altitude sickness. Alone, Zurbriggen continued and reached the ridge linking the north (6,960 m) and south (6,930 m) summits. At the end of his strength, he had to descend again.

Matthias Zurbriggen, Fitzgerald and his companions © Geological Society of London

Another attempt on January 14, 1897. This time, FitzGerald collapsed at around 6,600 meters, not far from the Canaleta. He allowed Zurbriggen to continue alone, and he reached the summit at around 5:00 pm. FitzGerald: “For the first time, the bitter feeling came over me that I had to give up, just below the summit of the great mountain to which I had devoted so much time and effort.”

The Polish way

After this hard-won victory, it would take another 37 years for a new route to be mapped out. The east face, although less terrifying than the south face, nevertheless requires real mountaineering skills to overcome the glacier descending from the summit. In the lower part, the famous penitents, blades of ice ranging from fifty centimetres to two meters in height, make progress very laborious. On March 9, 1954, a Polish team of four climbed the glacier: the Polish Way was born.

The South Face: Aconcagua's last great virgin face

1950: in Nepal, the great national expedition led by Maurice Herzog conquered the first “8,000”. Now it's the turn of young contemporary mountaineers to dream of their Annapurna. Among them, a band of friends, inveterate “bleausards” (they assiduously climbed in the Fontainebleau forest), lined up large-scale races in the Alps. Two names stand out: Lucien Bérardini, with his Mediterranean gouaille, and Robert Paragot, an almost Parisian “titi”. Both were members of the prestigious Groupe de Haute Montagne (GHM), which brought together the crème de la crème of French mountaineering.

In 1953, good fortune smiled on them. René Ferlet, secretary of the Club Alpin Français on his return from the Fitz-Roy, wanted to mount an expedition to the south face of Aconcagua, the only untouched face on the roof of the Andes. Paragot, the first to be approached, enthusiastically accepted, and had little difficulty in getting his colleague Lucien on board. They were joined by Pierre Lesueur, Edmond Denis, Guy Poulet and Adrien Dagory, all experienced mountaineers.

An expedition of broke but enthusiastic friends

Ferlet asks them to finance the trip. Paragot: “Ferlet took our [boat] tickets. One-way tickets. We figured there was no point in wasting money. We could die in the mountains. It wasn't a national expedition, but an expedition of friends, as broke as they were enthusiastic“. In Buenos Aires, they were received with great pomp, even being invited to an audience with Juan Peron, Argentina's charismatic president.

At the beginning of February, they set to work at the camp now known as Plaza Francia. Paragot: “Here we are at base camp. The horizon is absolutely blocked by a wall seven kilometers wide and three kilometres high.

The ascent soon proves to be difficult. Aconcagua, a mountain of volcanic origin, offers little or no good rock. Paragot again: “Every time you hold a hold, you never know if it's going to support you or if it's going to stay in your hand.”

There are no meters-of-altitude Sherpas here, no one to share the hard work of successive, grueling portages. They have to assemble everything themselves: tents, bivouac equipment, fixed ropes. Progress is slow, nerve-wracking and they suffer from cold and thirst, but morale is high. In fact, they finally abandon the Himalayan progression on fixed ropes laid out along the route. Too long, and the wall too steep. They'll make it to the summit in one go, using the latest technology.

.jpeg)

The Paragot-Bérardini team grappling with the loose rock on the South Face © Archives du GHM

Six days of storms follow. The snow piled up, the avalanches roared. When they set off again, they had to make tracks through the powdery snow. Above camp 3 (5,500 m), they wanted to believe that the summit was not far away, or at least that the main difficulties were behind them. But at 5,800 m, there was no turning back. It was impossible to set up a single piton, or any serious mooring for abseiling. They had to reach the summit, almost twelve hundred metres higher, at all costs.

The struggle for survival

Exhausted by the weight of their packs, they took a radical decision: to abandon all bivouac equipment, except for comforters. In any case, the alcohol for the stoves also froze. In the difficult passages, the lead team tries to install a few meters of fixed rope for the next group. Berardini: “... [we] found it extremely difficult to pull ourselves up these fixed ropes by the strength of our wrists, because in those days there weren't yet these wonderful little devices called 'jumars' (self-locking handles)”.

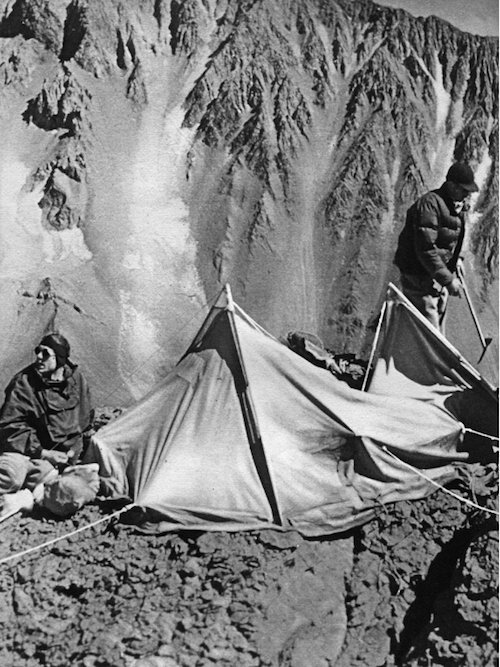

Camp 2, last “comfortable” camp © Archives GHM

At the fifth, precarious bivouac, hanging in the air at 6,500 meters of altitude, they hit rock bottom. Berardini: “It's been seven days since we left Camp 1. There are no supplies, no possibility of making water: our bodies are deteriorating very quickly. (...) If one of us had wanted to jump into the void, I don't think the others would have done anything to stop him.

Lucien Bérardini, indomitable, his fingers frozen (he had to take off his gloves to overcome the most difficult rock passages), managed to get them out of there, on a last, mind-boggling day. At 5 p.m. on February 25, 1954, they reached the summit.

The return journey, despite the victory, was a real ordeal due to the severe frostbite suffered by all, with the exception of Robert Paragot: “Everyone had frozen feet, blue toes and some well beyond the toes. I had nothing. I remember feeling ashamed (...) I felt like I'd cheated.

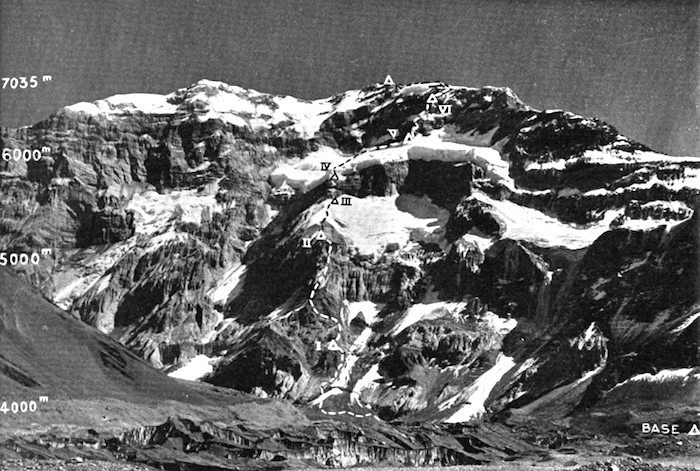

The 1954 route on the south face of Aconcagua © GHM

At the Mendoza military hospital, Robert looks on in horror as the surgeon prunes the toes with secateurs. Only Guy Poulet's screams convince him to stop the massacre and give him a general anaesthetic!

Aconcagua: an expedition not to be taken lightly

If, today, Aconcagua is considered an easy climb, the setbacks experienced by the first mountaineers to attempt it, in particular those of the FitzGerald expedition on its six attempts, bear crucial testimony. While there are no technical difficulties on the normal route, the altitude is there, and the wind is formidable. An expedition not to be taken lightly.

Climb Aconcagua at 6962 meters in Argentina, highest peak of America.

Watch an animation of the Aconcagua ascent below:

Text and animation by Didier Mille

Expeditions Unlimited blog

Expeditions Unlimited blog