2nd May 1964. The race for the fourteen "8,000s" officially came to an end. Fourteen short years separate the victory of Herzog and Lachenal on Annapurna I (3 June 1950) and that of the Chinese team led by Xǔ Jìng. But one ambiguity remains. The short account of the ascent published in the Alpine Journal, the prestigious magazine of the British Alpine Club, mentions an altitude of 8,013 m for the summit reached. In fact, this is the western antecima, sometimes erroneously called the central summit, separated from the main summit (8,027 m) by a long snowy ridge. Doug Scott, a famous climber and himalayist, was the first to express doubts during the British expedition in 1982. After all, perhaps they were the real winners!

A look back at the first ascent of the smallest but most controversial of the 8,000 metres.

See all our climbs above 8,000 meters.

Gosainthan, Shishapangma or Xixabangma: 3 names for the same summit

The twists and turns of geopolitics often lead to geographical curiosities. Today, the 1,389 km Sino-Nepal border follows the line of the highest peaks. Everest and Cho Oyu have a Chinese north side and a Nepalese south side. But between 1949 (the annexation of Tibet) and 1960 (the Sino-Nepalese Friendship Treaty), the limits of the border remained unclear. In 1950, Nepalese maps placed Gosainthan in Nepal. Five kilometres north of the Langtang peaks, Shishapangma, as the Tibetans call it, could just as easily have straddled the border.

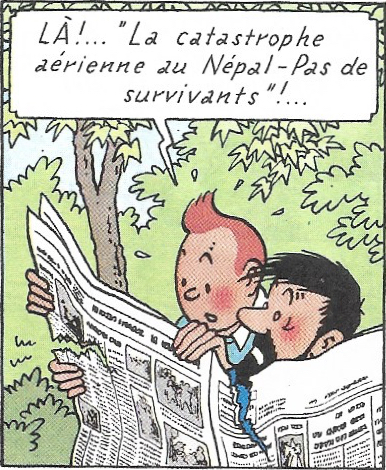

But the final agreement places the Gosainthan, dear to Hergé (Tintin in Tibet, written in 1958-59 and published in 1960), entirely in Tibet, and therefore in China. Its official name will henceforth be Xixabangma.

© Hergé-Tintin au Tibet

For the glory of Mao

In 1954, the clandestine Austrian expedition led by Herbert Tichy conquered Cho Oyu from the north face (China), under the noses of the mountaineers of the young Communist Republic.

In 1956, the Japanese, who had always been their adversaries, conquered Manaslu (8,163 m). The honour of Mao Tse Toung's troops was at stake.

In 1960, the Chinese reached the summit of Everest via the coveted North Face where, before Tibet was closed, Mallory, Somervell, Norton and so many other Western mountaineers had set numerous altitude records. The eyes of the young Communists then turned to Xixabangma. Forbidden to Westerners, it could hardly resist them for long.

On the way to Xixabangma

At the beginning of 1964, an expedition of 195 members (!) was set up: the size of the country. And that's saying something. Hsu Ching, leader of the victorious Everest expedition, was put in charge of operations. Geologist Wang Fu-Chou, one of the three summiters of the Chomo Lungma, also naturally finds his place: you don't change a winning team. A host of climbers from different regions of the People's Republic of China followed: Hans, Tibetans, Manchus and Huis. Egalitarian communism gives everyone a place. The youngest of them is nineteen.

A large scientific team accompanies the climbers.

Shishapangma to the north-east. The two summits are clearly visible.

On 18 March 1964, the expedition set up base camp at an altitude of 5,000 metres, at the foot of the north face, but thirty-six kilometres from the summit! A Himalayan outpost, the massif was subjected to the almost uninterrupted onslaught of violent winds sweeping across the immense plains of Tibet, without encountering the slightest obstacle. The wind would be their main adversary throughout the climb.

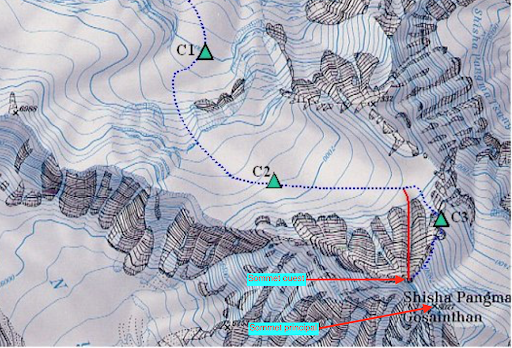

Three weeks of to-ing and fro-ing between glacial moraines led to a string of camps. Camp I: 5,300 m, camp II: 5,800 m, camp III: 6,300 m, camp IV: 6,900 m.

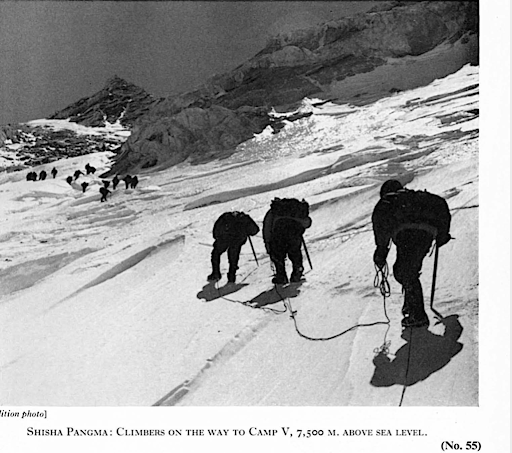

On 6 April, five tonnes of equipment were stored in the various camps. Camp II was used as an advanced base camp. On 7 April, the real work began. A cohort of climbers, divided into two groups of 37 and 12 members (the most experienced), took it in turns to make the route and the portages. To the credit of the Chinese climbers, there are no high-altitude Sherpas here. Camp V: 7,500 metres, and finally, on 21 April, camp VI at 7,700 metres, just 313 metres from the summit. By way of comparison, the last camp on the north face of Everest was 382 metres below the summit.

On the way to Camp V (7,500 m) © Alpine Journal

Back to base camp for everyone, waiting for a weather window. The news reached them: an exceptional period of stable fine weather was due to set in over the next few hours.

25 April, all hands on deck. There, at an altitude of over 5,000 metres, the whole team sang the national anthem in front of a sculpture of Chairman Mao's bust brought in especially for the occasion. Hsu Ching, the expedition leader, and Wang Fu Chou, the Everest hero, lead the roped party: 6 Hans and 7 Tibetans. Ideal parity, with nothing for the West to complain about.

Progress through violent gusts of wind. Camps IV and V, buried under a thick layer of snow, had to be cleared with shovels. 1st May: they reach camp VI. At 6am on 2 May, divided into three roped parties, the 13 himalayists set off for the summit. The weather was fine, but the wind was gusting to 90 km/hour. At around 7,800 m, a twenty meters wide patch of ice required some steps to be cut. Suddenly, Wang Fu Chou, who was leading the way, lost his footing. It was a dangerous slide: below, seracs and gaping crevasses awaited him. Miraculously, his rope-mates stopped the fall.

Once they had cleared this final hurdle, they struggled up the last slopes before reaching what they described as the "summit". On 2 May 1964, the thirteen Himalayans stood on the highest mountain range in China. The honour of Mao and the PRC was safe. But then...

The team at the summit (8,013 m). Leader Hsu Ching (third from right) announces victory over the radio.

But they are still 280 m from the main summit. Alpine Journal

Victory in question

In the report written by Chou Cheng, deputy leader of the expedition, published in the Alpine Journal in 1964, the altitude indicated is 8,013 m. However, a summit a few meters higher than this is found further on, at the end of a long ridge of bumpy, very tapered snow. The violent wind, the number of participants, the distance to be covered and the time needed to complete the route are all factors that the 'winners' don't dwell on. The conclusion is obvious: they have not climbed this ridge.

In 1982, Doug Scott led a British expedition to the south-west face of Shishapangma. Referring to their arrival at the west antecima, he wrote: "We continued to the east summit, which is about ten meters higher and 280 meters away [from the antecima]. It may or may not have been climbed previously".

Yves Détry, a French mountain guide and member of "L'esprit d'Equipe", an expedition led by mountaineer Benoît Chamoux in 1990, which also stopped at the west antecima, confirms: "As he (Chou Cheng) doesn't mention a tapering ridge to go from the west summit to the main summit, I think and am pretty sure that they climbed the west summit".

© Yves Détry

For this reason, the late Elisabeth Hawley, the uncompromising journalist and accountant of Himalayan ascents, based in Kathmandu since 1959, refused to record the ascent by Benoit Chamoux and the seven members of "L'Esprit d'Equipe". Mountaineer Ed Viesturs, the only American to have climbed all fourteen of the "8,000" to date, was forced to return to the mountain twice to satisfy its demanding criteria. The crossing took him an hour and a half each way.

Shishapangma is the only 8000 whose first ascent remains uncertain. Only the words of the first climbers, proclaiming their victory, are authentic.

The ridge seen from the west antecima. The main summit in the background. © edvisturs

If you're planning to take part in the challenge of 14 summits over 8,000 m, you'll need to reach the main summit. And to do that, you'll need to complete the long final traverse at an altitude of over 8,000 metres... and come back.

Climb Shishapangma at 8027 meters in Tibet

Climb Nanga Parbat at 8126 meters in Pakistan

Expeditions Unlimited blog

Expeditions Unlimited blog