Nanga Parbat, ‘the killer mountain’. Between Mummery's first attempt in 1895 and Hermann Buhl's first ascent in 1953, 30 people lost their lives on its slopes. A sad record. First the brilliant climber Mummery, then two Austro-German expeditions in 1934 and 1937 paid a heavy price. With its three huge, complex, avalanche-prone slopes, Nanga Parbat posed a real problem for the route planner. Unlike most of the 8000m summits, there is no obvious route to the summit. Until the first ascent in 1953, all the efforts were concentrated on the north face and the Rakhiot glacier. We take you back to those tragic moments in the history of Himalayan climbing.

See all our climbs above 8,000 meters.

Nanga Parbat: the 8,000 m accessible since the 19th century

At the end of the 19th century, the whole of India, right up to the borders of present-day Afghanistan, was under the authority of the British Empire. In Kashmir, Srinagar, the Venice of India, appreciated by Her Majesty's subjects for its temperate summer climate, was the ideal starting point for reaching the Nanga Parbat massif, less than 120 kilometres to the north as the crow flies. A three-week trek over the now forbidden Tragbal and Burzil passes (3,530 m and 4,132 m) provides easy access to the Rupal side, the mountain's imposing south face. German explorer Adolf Schlagintweit showed the way as early as 1856.

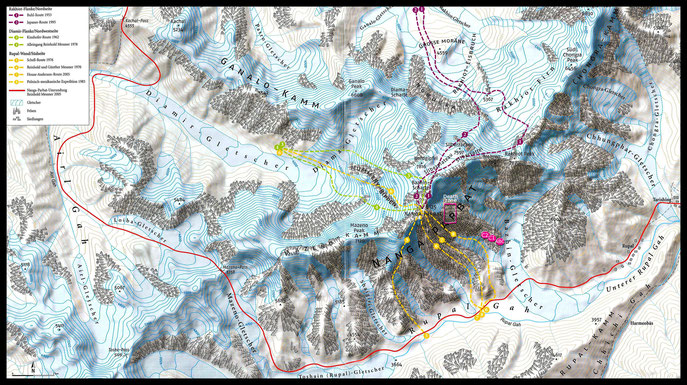

North side: Rakhiot - South side: Rupal - West side: Diamir © mazenoridge.com

Mummery, the virtuoso of the Alps, underestimates the Himalayas

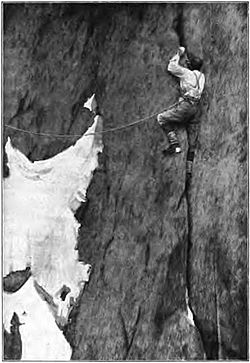

Albert Frederick Mummery, the man from Le Grépon, is considered to be the founder of sport and unguided mountaineering. An excellent climber with surprising agility, his talents as a ‘gymnast’ put him far ahead of the protagonists of the time. In 1888, he made the difficult ascent of the second highest peak in the Caucasus, the Dykh Tau (5,205 m), in the impressive Bezengui wall. His biggest flaw: wanting to apply his mountaineering skills to other mountain ranges. What brought him luck in the Alps and the Caucasus should also be applicable to the Himalayas. CQFD. His philosophy: climb for pleasure with his best friends. He doesn't care about mountain exploration, as it's understood in these days of discovery. Mummery: ‘To tell you the truth, I hadn't the faintest idea what a theodolite was, and as for chart tables, the very name horrifies me.

Mummery in the eponymous crack at Le Grépon, level V today! © Lily Bristow.

In 1895, Mummery was 40 years old. He was bursting with health and optimism. On 17 July, he and his companions arrived in Tarishing, at the base camp in the Rupal valley. Not in the least intimidated by the almost five thousand meters of ascent that this South Face represents, he wrote to his wife: ‘I don't think there will be any serious mountaineering difficulties on the Nanga, it will mainly be a question of endurance’.

The Col de Mazeno, the only passage between the South and West faces

But the harsh reality of the altitude quickly contradicted his confidence. On 18 July, he failed on Chiche Peak (5,860 m) (1), due to a lack of acclimatisation.

Chiche Peak, a beautiful satellite summit of Nanga Parbat © Christian Walter, Club Alpin de Saxonnie, Germany.

Chiche Peak, a beautiful satellite summit of Nanga Parbat © Christian Walter, Club Alpin de Saxonnie, Germany.

Mummery agrees to postpone the ascent of the Nanga, in favor of a few days' reconnaissance. On July 20, he and his companions crossed the Mazeno glacier pass to reach the Diamir valley on the mountain's western side. In the middle of the Diamir glacier, a rocky spur leading below the summit seemed an obvious and direct route: the Mummery Ribs. A return trip to the base camp on the Rupal slope is nevertheless necessary to collect the equipment. First unsuccessful attempt to cross the Mazeno ridge as quickly as possible (avoiding the long detour via the col). It ends in a cul-de-sac at 6,400 meters. The only viable solution: the Mazeno pass.Back at the Tarishing base camp, exhausted, the brilliant climber collapses: the walk, the trek, the incessant ascents and descents don't suit him.

Diamir Gap: the first Himalayan tragedy

Quickly back on his feet, here he is on the slopes of Chongra Peak (6,824 m), east of the main summit of Nanga Parbat. Another failure. After a final false start, still hoping to cut the Mazeno ridge as short as possible, he resigned himself to another grueling crossing of the pass. By August 15, he and his companions were finally at work in the Diamir valley: this time, Mummery was determined, it would be the right time. If he could reach the top of the Mummery Ribs and set up a second camp at almost seven thousand meters, the summit would be his. On August 18, 1895, their first real attempt on the Nanga failed at six thousand two hundred meters. Defeated, Mummery refused to make the long detour through the lower valleys back to Kashmir.Convinced that at the top of the Diamir glacier, a gap gave access to a shortcut, he set off again with two porters.No one will ever see them again.

In a letter to Edward Whimper (2), one of Mummery's contemporaries prophesied before his departure for Nanga Parbat: “I cannot imagine that Mummery could devote either the time or the money necessary to succeed in such a remote and difficult field of exploration. Also, I don't expect any significant results."

These first three Nanga Parbat victims open a long list of fatalities.

The Germans set their sights on Nanga Parbat

A long period followed, during which Nanga Parbat returned to its superb isolation. Then came the 1930s. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, Mount Everest has been the exclusive preserve of the British Empire. K2, the world's second highest peak, seemed untouchable. In 1930 and 1931, the Germans launched two unsuccessful expeditions to the world's third highest peak: Kangchenjunga. Its endless ridges and vertical faces resisted all their efforts. And Nepal, with its seven “8,000s”, keeps its borders hermetically sealed.

Only Nanga Parbat remains politically accessible.At the time, curiously enough, the difficulties appeared to be fewer than on the other summits. Germany, where Nazism was taking hold, had a major goal to achieve.Until the final victory in 1953, nothing could distract our German neighbors from the summit.

The German-American expedition of 1932

Willy Merkl, accompanied by seven experienced German-speaking mountaineers, an American mountaineer and an American woman climber, launched the first attempt. Incongruous in this world of men, Miss Elizabeth Knowlton was the first woman on the slopes of an eight-miler. Among them, Austrian Fritz Wiessner, the future hero of K2, not yet a naturalized American. Merkl chose not to call on the Darjeeling Sherpas, hoping that the Balti and Hunza porters would be up to the task.

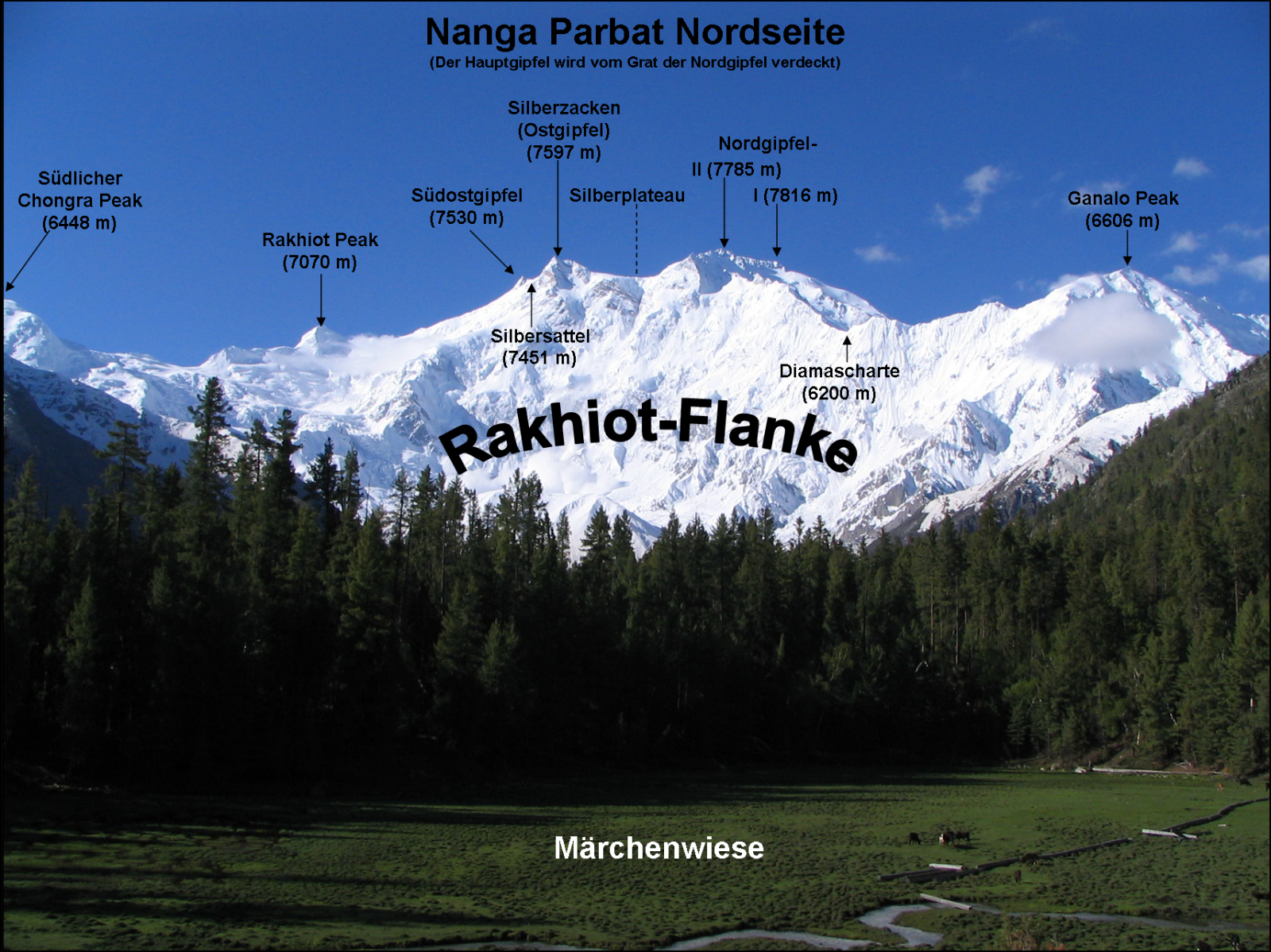

The north face of Nanga Parbat, the ridge runs for three kilometres between Rakhiot Peak and the summit. © de.academic.com

The Rakhiot glacier and the east ridge, a likely route to victory

Setting off from Srinagar on 23 May, the expedition arrived on 17 June at the verdant alpine meadow of Fairy Meadows (3,300 m), at the foot of the Rakhiot slope. Mummery's misadventures between the Rupal and Diamir were the reason for this choice: the less steep northern slope may hold the key to success. Between mega-avalanches and ascents of the tormented Rakhiot glacier, they managed to set up four camps. On 8 July, the highest camp, at 6,100 metres below Rakhiot Peak, became the advanced base camp. Most of the subsequent expeditions used the same location. On 16 July, Aschenbrenner and Kunig reached the summit of Rakhiot Peak (7,070 m). The ascent was too difficult for the porters: to avoid the summit, they had to cross the steep, exposed slopes below the north face of Rakhiot Peak. This enabled them to reach the east ridge where they successively set up camps V, VI and finally VII at 7,100 metres. Three kilometres still separate them from the summit. Unfortunately, the porters became exhausted at altitude and the bad weather forced them to pack up on 2 September. Nevertheless, they opened the road to the summit, a great achievement in itself.

1934, drama brewing

Willy Merkl did not admit defeat. The brand new Nazi government granted him 200,000 Reichmarks on condition that he brought back a film glorifying his heroism. Fourteen climbers in all, including Willo Welzenbach, one of the best pre-war glaciers, and two strong Austrian mountaineers and skiers, Aschenbrenner and Schneider. Peter Müllritter will be in charge of the cinematography.

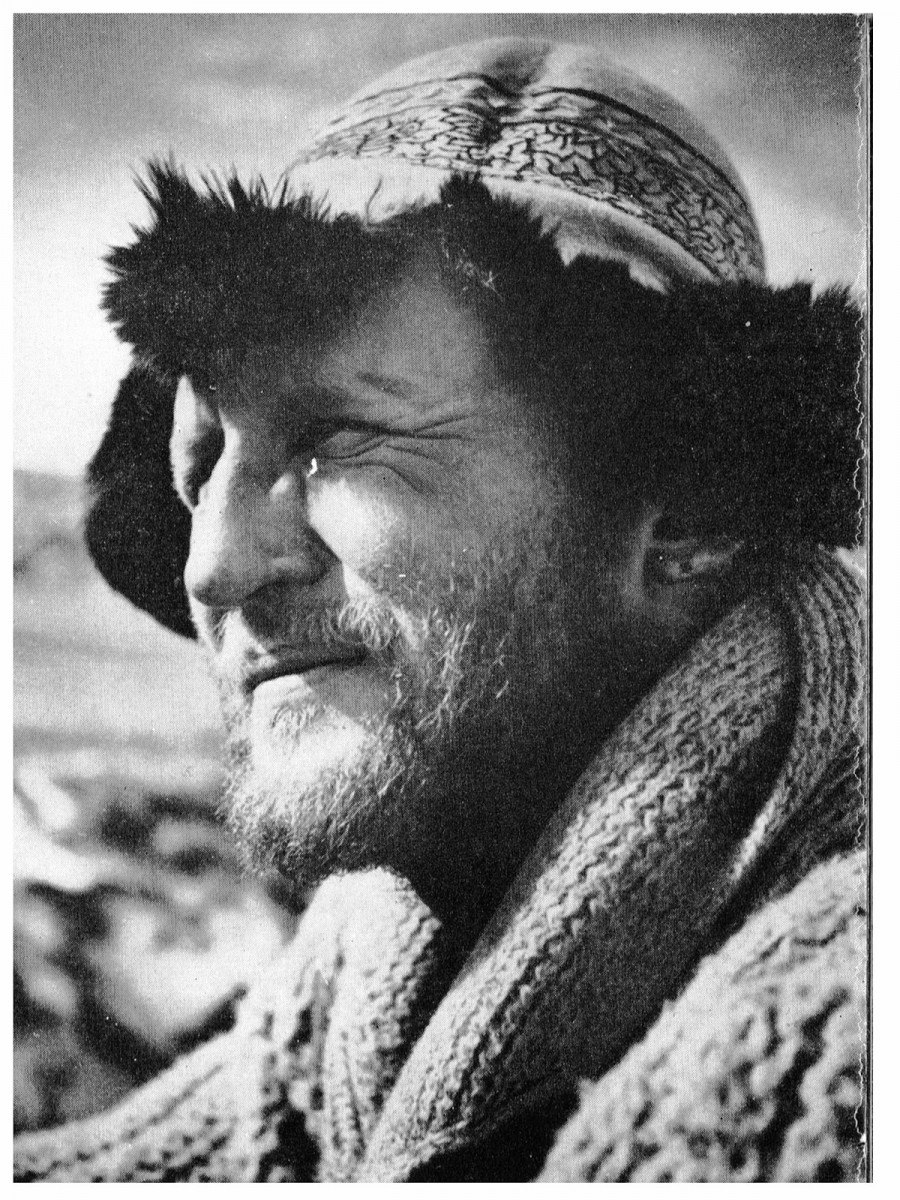

Willo Welzenbach, the most brilliant pre-war glaciarist.

Willo Welzenbach, the most brilliant pre-war glaciarist.

From Camp IV to the summit, without a fallback camp

With experience under his belt, Merkl called on 35 Sherpas from Darjeeling, including several ‘Tigers’ (3). The expedition got off to a bad start: as early as camp II, Alfred Drexel, who had climbed too quickly to the top, suffered a devastating pulmonary oedema. He died on 10 June. Between the funeral, a strike by the Balti porters and several days waiting for a caravan to arrive with the extra tsampa the Sherpas needed, the days passed inexorably. The monsoon could arrive any day now. Tension mounts between Merkl and other members of the expedition, including Willo Welzenbach, who has doubts about his leadership qualities. Contrary to all the safety rules of the time - setting up a series of camps close together to ensure a safe retreat - Merkl took the decision on 1 July to have everyone, mountaineers and Sherpas, climb together from camp IV to the summit. They took only the bare essentials with them, leaving a few makeshift shelters en route as intermediate camps. They had to succeed at all costs.

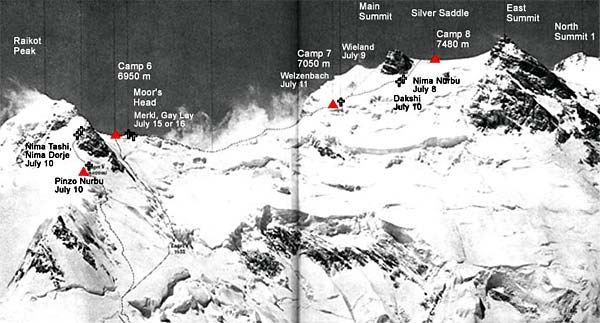

The long ordeal on the east ridge.

The trap is closing

The route to the summit involves climbing very high up the north face of Rakhiot Peak, crossing below the summit and then descending 120 meters down the opposite side. This is followed by two kilometres on the east ridge before reaching the Silver Saddle, the start of the plateau leading to the foot of the summit ridge. A real trap at high altitude. On 6 July, they reached the Silver Saddle (7,600 m). Despite a strong wind, they persevered on the snowy plateau that sloped gently upwards towards the summit ridge. Camp VIII, or rather bivouac, at 7,900 meters, in precarious conditions, given the limited amount of equipment on board. But the wind became a hurricane, accompanied by heavy snowfalls, putting an end to their hopes of reaching the summit. On 8 July, the retreat turned into a tragedy. A total of 16 participants, 5 Westerners and 11 Sherpas, struggled for a week on the east ridge at an altitude of over 7,000 meters. Aschenbrenner and Schneider were the first to descend and, roped up with three Sherpas, attempted to climb back up to Rakhiot Peak. A gust of wind threw one of the Sherpas down the slope. The fall was stopped, but his rucksack containing the only sleeping bag in the possession of the three Sherpas disappeared down the slope. If they don't reach Camp IV that evening, their chances of survival are slim.

Aschenbrenner and Schneider abandon their companions

A terrible moment arrived: Aschenbrenner and Schneider untied themselves and abandoned the three Sherpas to their fate, without a thought for their other comrades in distress. At 19:00, they arrived at camp IV: rescued. The speed with which they made the descent can be explained: having taken their skis with them, they probably put them on shamelessly, to escape to their lives. An unthinkable attitude, never mentioned in the official and controversial versions. But how else to explain their astonishing schedule?

Aschenbrenner and Schneider on their way to camp 2, skis on their backs

© Jonathan Neale, Tigers of the Snow.

The Sherpas on their own

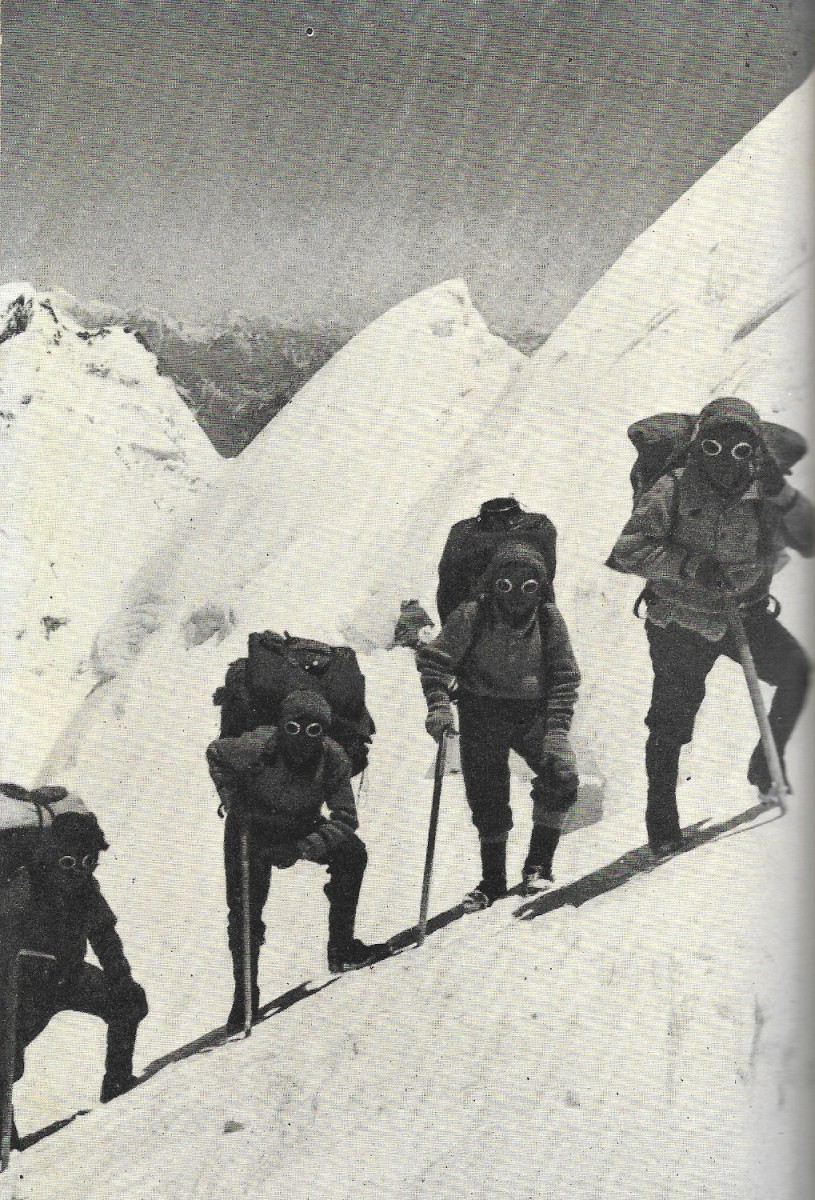

Behind them, it was a debacle. The three Sherpas miraculously survived two improvised bivouacs, at over 7,000 meters, without any protection. On 10 July, four other Sherpas joined them. On Merkl's orders, due to lack of space in the only tent left for camp VII, they had to descend to the shelter of camp VI. The tent, buried in the snow, provided derisory protection against the storm. The next day, staggering with fatigue, they nevertheless joined the three other Sherpas. Together, they began the dangerous journey below Rakhiot Peak. Finally, they reached the fixed ropes leading to Camp V. The slope was steep, they had no crampons (!) or karabiners and had to hold on to the rope at arm's length.

The Sherpas on their way to Camp V. Note the absence of crampons.

Tragic outcome

Two die of exhaustion along the ropes. A third collapsed two meters from the tent at Camp V. On the afternoon of 10 July, Da Thundu, Pasang Kikuli, Kitar and Pasang Picture, dazed, managed to reach camp IV. At what price! Ang Tshering arrived 24 hours later. Like the grains of a funeral rosary, the bodies of Ulie Wieland, Willo Welzenbach, Willy Merkl, Nima Norbu, Dakshi, Gaylay, Nima Tashi, Nima Dorjee and Pinzo Norbu were strewn along the eastern ridge.

Political and media pressure, a lack of understanding of the effects of altitude and a poor strategy from a leader obsessed with the summit - all the ingredients for disaster were there.

The Sherpa survivors of the 1934 tragedy: Da Thundu, Pasang Kikuli, Kitar, Pasang Picture. Ang Tshering arrived 24 hours later. Jonathan Neale - Tigers of the Snow.

The disaster of 1937

Despite the tragedy, by 1937 the necessary funds had been raised to launch a new assault. The mountain would not have the last word. A team of eight participants, including film-maker Peter Müllritter, a veteran of the 1934 expedition, arrived at the base camp at the beginning of June. Snow fell heavily every day, forcing them to retrace their tracks every day. Despite this, they managed to set up the first four camps. By mid-June, the entire expedition, with the exception of Uli Luft, who remained at base camp, was assembled at camp IV. That's seven climbers and nine Sherpas. During the night of 14 to 15 June, a slice of serac detached itself from the upper slopes of Rakhiot Peak, setting in motion a huge avalanche the likes of which only the Himalayas can produce. The entire camp and its inhabitants were instantly engulfed. Peter Müllritter did not escape his fate, nor did Pasang Picture, a survivor of the 1934 tragedy.

The legend of a curse began to spread in the valleys surrounding Nanga Parbat. Paul Bauer, the leader of the two unsuccessful German attempts on Kangchenjunga in 1929 and 1931, was commissioned to find the bodies. It was a painful ordeal, but one that convinced him to return and complete the ascent undertaken by his unfortunate compatriots.

1938: monsoon stops all efforts

Paul Bauer set off again with a dozen companions, including two survivors of the tragic expeditions of 1934 and 1937, Fritz Bechtold and Ulrich Luft. All with the generous financial support of the Nazi government. They really wanted this victory on Nanga Parbat. And for the first time in the Himalayas, parachute drops were planned during the ascent to provide logistical support. Another novelty was the use of short-wave radios linking them to the outside world, facilitating communications between Camp IV and the base camp. On 11 June, the first parachute was successfully dropped over the base camp, and on 2 July another was dropped at camp IV. But constant snowfall delayed progress. When they finally reached the east ridge, they discovered the perfectly preserved bodies of Sherpa Gaylay and Willy Merkl. On 24 July, they reached 7,300 meters below the Silver Saddle, where bad weather forced them to abandon the route.

1939, reconnaissance of the Diamir Basin

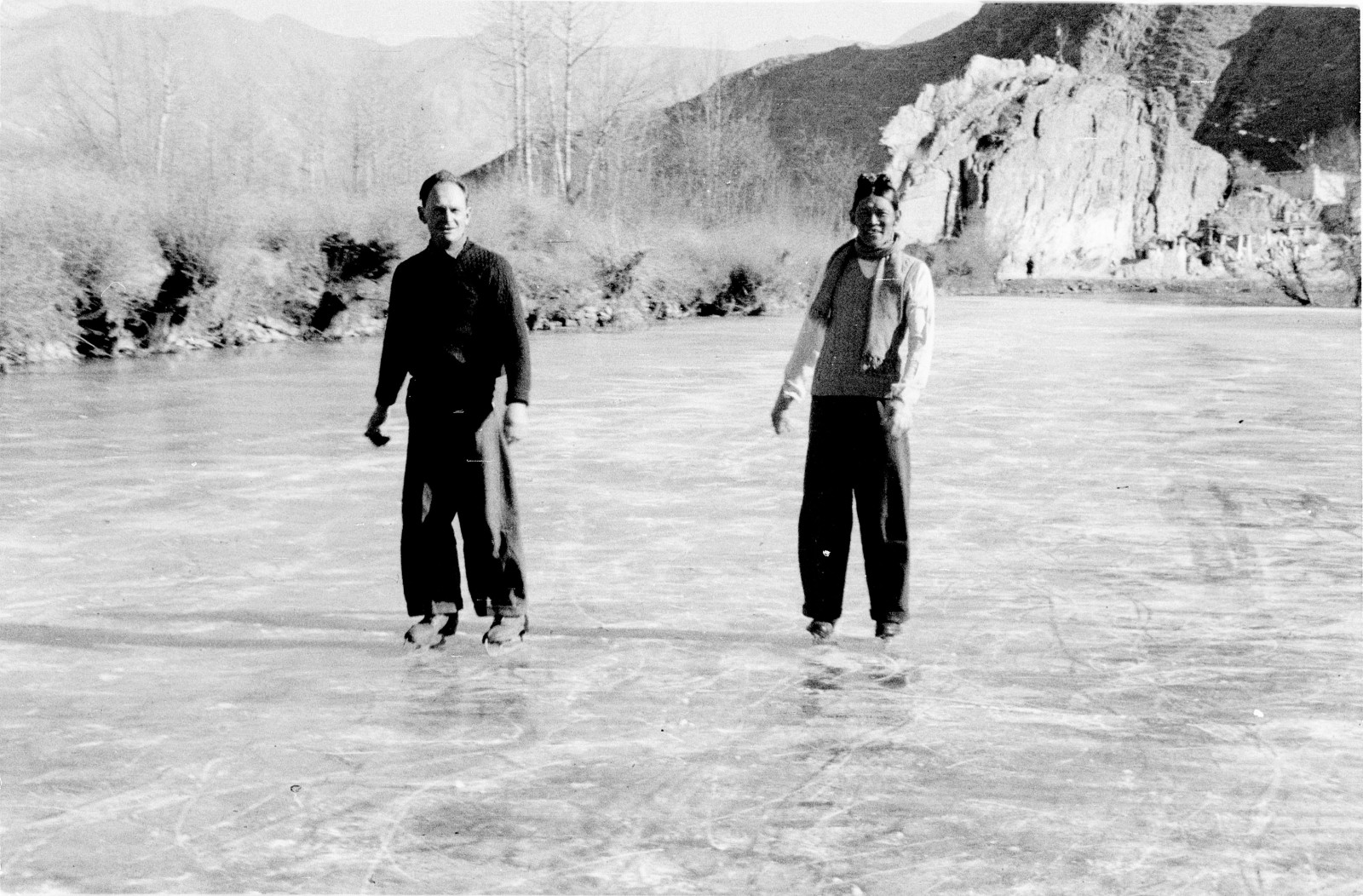

The unfortunate expeditions of 1934 and 1937, plus the failure of 1938, finally convinced the Himalayan Foundation to carry out a reconnaissance of the Diamir slope. After all, Mummery had already shown the way in 1895. And the trap of the east ridge, with its obligatory 120 meters ascent, was now acting as a real deterrent. So in the summer of 1939, a small team of four climbers, led by Peter Aufschnaiter, set off for the Diamir slope. Among them was Heinrich Harrer (4), future tutor to the Dalai Lama. With its avalanches and rockfalls, the Diamir slope was hardly conducive to climbing. They set off again, convinced that the Rakhiot route was still the right choice. Arriving in Karachi, the declaration of war led to their arrest and internment in a camp, from which Aufschneiter and Harrer later managed to escape to Tibet. It was not until 1953 that the final round was played on Nanga Parbat.

Climb Nanga Parbat at 8126 meters in Pakistan.

Heinrich Harrer ice-skating in Lhasa in the 1940s © Völkerkundemuseum der Universität Zürich.

Text by Didier Mille.

___

1. Chiche Peak, south of Nanga Parbat, was climbed for the first time in 2010 by Stephan Wolf and Christian Walter, president of the Saxony section of the German Alpine Club.

2. Edward Whimper, the most famous mountaineer in the United Kingdom after his victorious ascent of the Matterhorn on 14 July 1865.

3. Tigers: honorary title awarded to the most valiant Darjeeling Sherpas, with several of the 8,000 expeditions to their credit.

4. Heinrich Harrer is the author of the best-seller Seven Years of Adventures in Tibet.

Climb Nanga Parbat at 8126 meters in Pakistan

Climb K2 at 8611 meters in Pakistan

Expeditions Unlimited blog

Expeditions Unlimited blog