‘The ascent of Makalu, a happy page in the history of the Himalayas’. It was with this pithy phrase that Jean Franco, leader of the French expedition to Makalu in the spring of 1955, summed up their magnificent victory on the fifth highest peak on the planet. The ‘more than 8,000’ summits previously climbed (Annapurna, Everest, Nanga Parbat, K2, Cho Oyu) saw no more than three participants reach the summit, thanks to the logistical support of everyone involved. At Makalu, spread over three successive days, all the climbers and the sirdar, nine participants in all, set foot on the summit of one of the giants of the earth. This success was due as much to meticulous preparation and acclimatisation as to the success of the 1954 reconnaissance. And to exceptional luck with the weather. We retrace this perfect adventure for you... And we take this opportunity to introduce you to our next ascent of Makalu in April 2022, guided by Serge Bazin.

See all our climbs above 8,000 meters.

After Annapurna, Makalu

Makalu... Mahakala. The Tantric Buddhist deity probably gave his name to the mountain. The destructive/protective god will bring luck to the French.

Mahakala, Buddhist avatar of the god Shiva

After the remarkable victory on Annapurna in May 1950, the Himalaya Committee was on a roll. The next objective was Everest. The Nepalese authorities granted permits first to the Swiss (1952), then to the British (1953), and finally to the French, but for 1954. The British victory took the wind out of their sails.

The superbly isolated Makalu, barely approached by Eric Shipton and Edmund Hillary in 1951 following the attempt on Cho Oyu, and in 1952 during the reconnaissance of Everest, offered the possibility of a great discovery, or even a new coup. The Everest permit, granted for 1954, was transferred to Makalu. Two permits had already been issued to the New Zealanders and Americans for the spring. An additional permit, issued to the French for the spring of 1955, gave them a second chance. So much the better, because given the knowledge available at the time, the extreme cold and the wind, an autumn ascent was unlikely to succeed. A reconnaissance on the flanks of the mountain in the autumn of 1954 gave them a better chance of making the attempt in the spring of 1955.

From then on, the French were lucky.

.jpg)

Makalu, the West Pillar. On the left, Makalu II or Kangchungtse © Serge Bazin

Sir Edmund Hillary is out of the game

Spring 1954: the Americans set the ball rolling. The first serious attempt was made. But they headed for the long south-east ridge, where bad weather and heavy snowfall stopped them at 7,150 metres. They returned empty-handed.

At the same time, the New Zealanders, led by Edmund Hillary (who became Sir Edmund after his victory on Everest), obtained permission to attack Baruntse and its satellites. During a reconnaissance, two climbers fell into a crevasse. An eventful rescue followed, with Sir Hillary breaking three ribs. Before long, his injury developed into a serious lung infection. His companions had to evacuate him under difficult conditions.

On 29 May and 1 June, George Lowe and Colin Todd, followed by Geoff Harrow and Bill Heaven, reached the summit of Baruntse. From this viewpoint, they could observe Makalu. For them, the right route was via the north-west face. They had to reach Makalu La (7,400 m), the pass on the north-north-west ridge separating Makalu II (or Kangchungtse - 7,660 m) from Makalu proper.

The route is open to French climbers.

Reconnaissance in autumn 1954

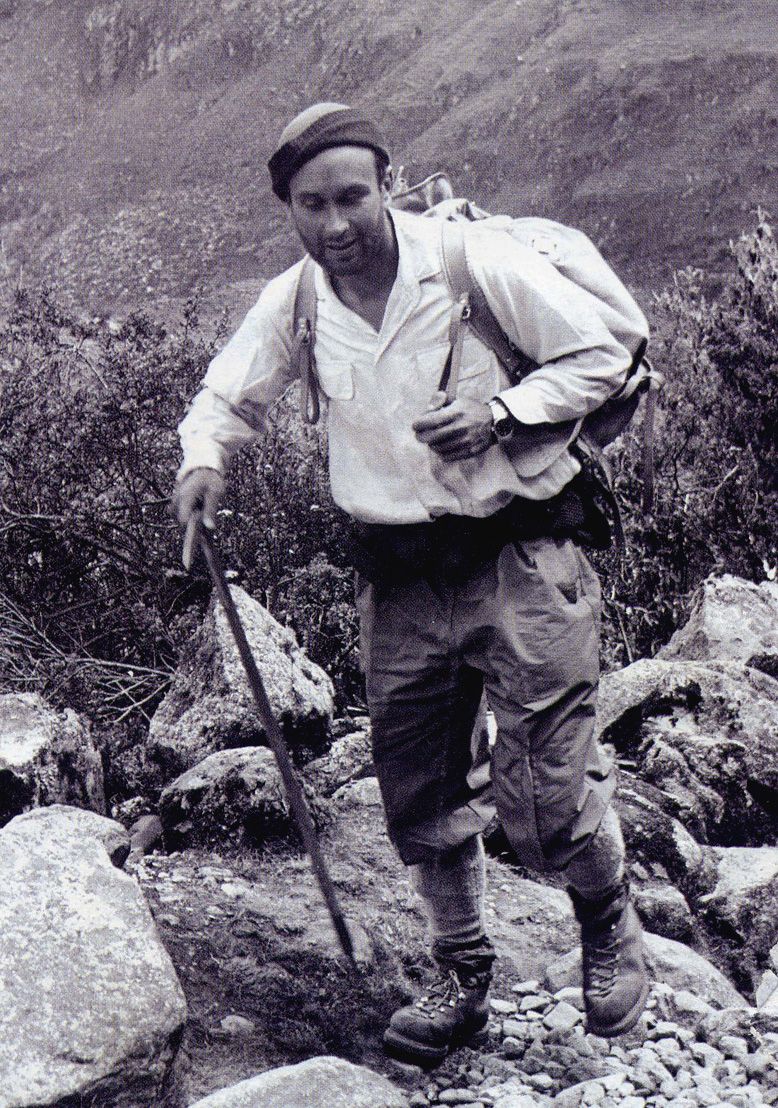

Jean Franco, a 40-year-old mountain guide, was entrusted by the Himalayan Committee with responsibility for the two forthcoming expeditions. He called on Jean Couzy and guide Lionel Terray, two veterans of the Annapurna victory in 1950.

These were the ‘belle époque’ of heavy expeditions: 180 porters and 6.5 tonnes of equipment to carry to the base camp, which they reached at the end of the monsoon.

To get the best possible view of the entire Makalu massif, they climbed several peaks at a steady pace, including Pethangtse (6,730 m) to the north. Terray: ‘The only reasonable option was to trace a spiral route starting from the foot of the north-west face, joining the north-north-west ridge via the route unsuccessfully attempted by the New Zealanders, then reaching the north face’.

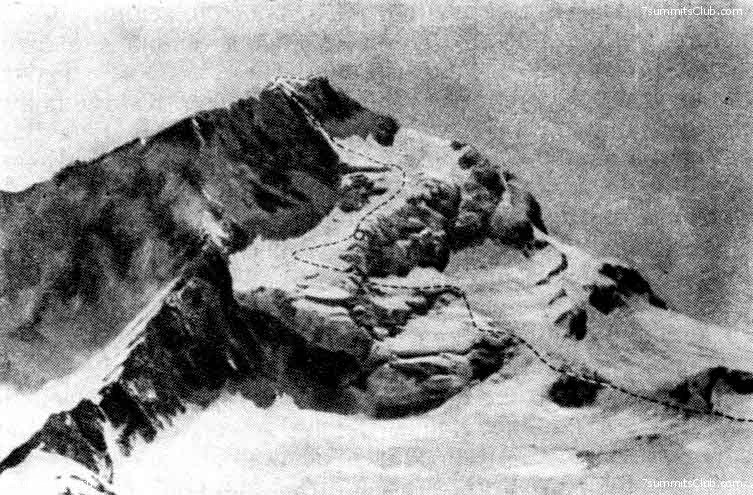

The ascent of the north-west combe of Makalu led them, in four successive camps, to the foot of the steepest part. They forced their way through and reached the Makalu La (7,400 m) where they set up camp V. From this camp, they made the first ascent of Makalu II, at the end of the north-north-west ridge. This gave them a good view of the north face of Makalu's summit pyramid. But the top of the route is still not visible.

The 1955 route, north-west side © summitclub.com

The 1955 route, north-west side © summitclub.com

Chomo Lonzo: tragedy narrowly averted

Despite winds in excess of 100 kilometres per hour, Couzy and Terray descended two hundred metres on the opposite side of the col and climbed the easy snow ridge that took them to the summit of Chomo Lonzo (7,797 m). This time, they had a clear view of the entire north face of Makalu: there was no doubt that the route to the summit was obvious. To get back up to the pass, they almost had to face a catastrophe. The wind had knocked over and covered the two emergency oxygen bottles they had left on the outward journey. Couzy wanted to continue, but Terray, exhausted, persisted in looking for the bottles. In the cold and icy wind, Mahakala's first helping hand: Terray finally found the bottles. Saved!

Lionel Terray, the guide who stood the test of time

The spring 1955 expedition

Eight climbers, a doctor and two geologists. So much for the alpine and scientific cast.

Today, in the age of globalisation where everything is easy, you need to have read Jean Franco's excellent account to fully appreciate the difficulties encountered in those far-off days.

Having to pass through customs

This time it wasn't 6.5 tonnes of equipment that had to be transported to Nepal via Calcutta, but 11 tonnes! The (humorous) account of the trials and tribulations of customs, in post-colonial India, in 40°C of humid heat, in premises where powerful fans are bent on blowing away the slightest document, is worthy of a Kafka novel. In addition to the usual mountaineering equipment, they carried heavy transceivers, compressed gas cylinders for heating, and, to top it all off, weapons and ammunition (Franco's hunting exploits would significantly improve the situation). More than enough to justify the mistrust of the local authorities!

From the very first days, three of the eleven members of the group had to stay behind. Jean Couzy first, in Calcutta. André Vialatte, who had just arrived in Biratnagar (Nepal), would have to return to Calcutta. Serge Coupé will have to wait in Dharan (Nepal).

The oxygen race

The oxygen cylinders, which Air France had planned to supply in abundance, were refused by Air France and travelled by sea. But the captain of the cargo ship changed route and stopped for an indefinite period in Rangoon, then the capital of Burma! Finally, Couzy left Rangoon by plane to collect the precious cargo and take it back, still by air (the airlines operating in Asia at the time were less fussy than Air France) to Calcutta, then to Biratnagar in Nepal. He then had to join Serge Coupé in Dharan, who was responsible for keeping the 55 porters waiting to transport the oxygen cylinders.

Where is the money?

When the three Indian airlines flights chartered for the Calcutta-Biratnagar leg arrived, one of Franco's trunks was missing, containing, he told us, ‘the entire treasure of the expedition, all our cash converted into rupees and small denominations’! This time, Vialatte stuck to his task and returned to Calcutta, where the precious trunk was eventually found... in a secret hiding place on one of the planes that had carried the group.

24 days of trekking

Despite all these setbacks, the approach march began. A broken track led from Biratnagar to Dharan. No fewer than 350 porters and 25 Sherpas from Darjeeling then took over, covering the paths along the river Arun to the last village: Seduwa. Beyond that, a mineral world awaits them. After 24 days' trekking, at the beginning of April, they set up camp at an altitude of 4,700 meters.

Perfect organisation

The portages were soon organised. Camp I at 5,300 meters on the moraine of the Barun glacier, at the foot of Makalu's impressive west pillar. Camp II at 5,800 meters in the north-west combe, and on 2 May, camp III, at 6,400 meters at the top of the combe. This will be their advanced base camp. A long sling traverse to the right takes them to the foot of the most difficult passage, the mixed couloir that gives access to the col. Camp IV at 7,000 metres. It was a tough battle to climb up the couloir and install the essential fixed ropes. Finally, here they are at Makalu La, where camp V has been set up at an altitude of 7,400 meters. They were at the highest point reached during the 1954 reconnaissance. The weather, which until then had been unstable, with snowfalls and wind every afternoon, was now fine. This was an exceptional stroke of luck, and it remained so for the next two weeks.

The highest bridge in the world

On 12 May, apart from Couzy and Terray, the top team already at camp IV, the whole team was reunited at camp III. Even André Lapras, the doctor, a neophyte at altitude, was present. The comfortable accommodation gave them the assurance of success: they could hold out whatever the weather. The atmosphere was just right, and they enjoyed a final game of cards: bridge!

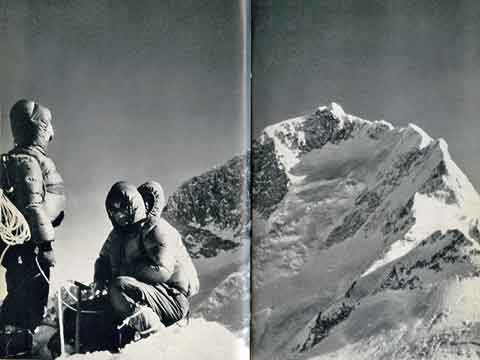

On 14 May, Guido Magnone and Jean Franco climbed to camp IV. The same day, Jean Couzy and Lionel Terray left camp V and set off with five Sherpas on the north face. Camp VI at 7,800 meters. The Sherpas descend. The other climbers followed at one-day intervals.

The North Face © Lionel Terray

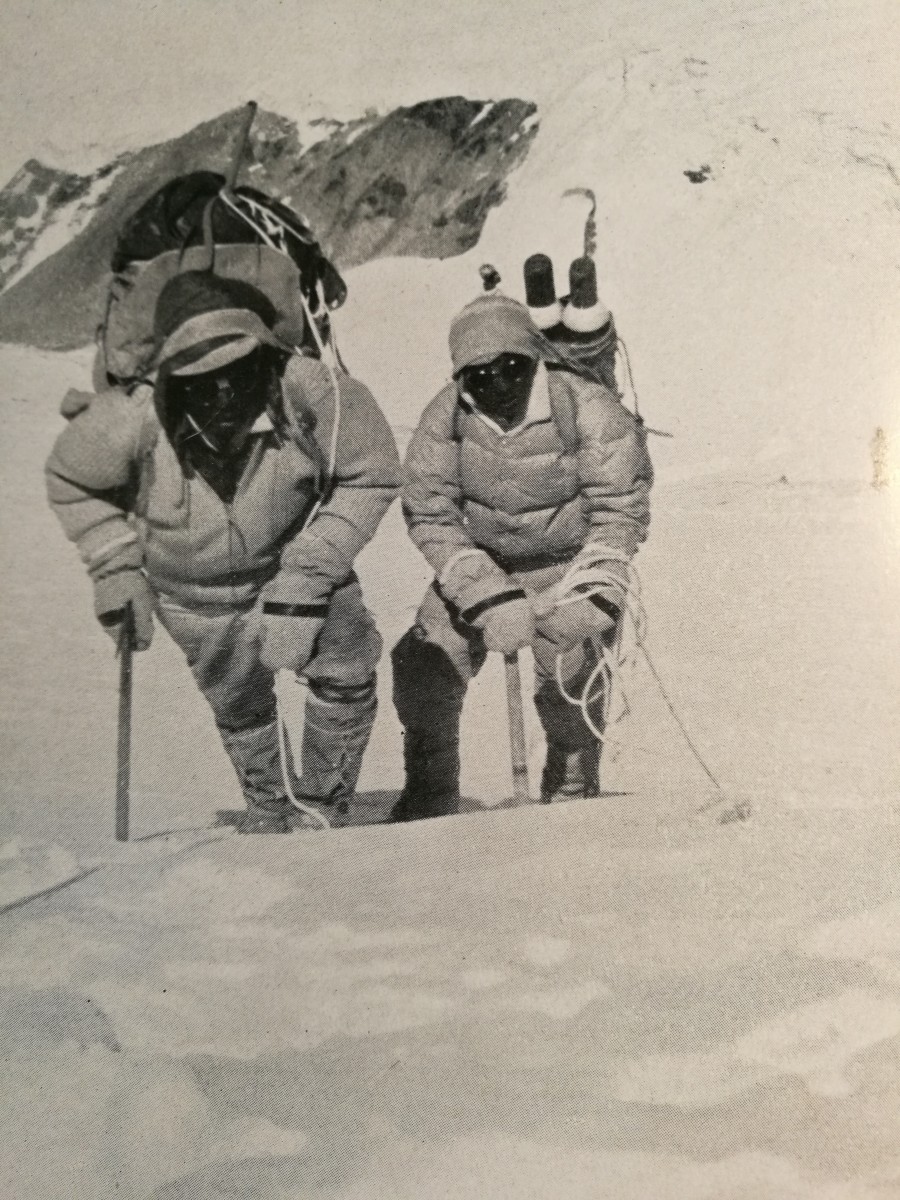

Glory to the Sherpas: ‘they are the real snowmen’.

While the Sherpas have regularly been thanked by the various authors of the period, Jean Franco offers them a veritable panegyric. Franco: ‘If Camp VI was set up here, it's thanks to you. And if today and tomorrow, the sahibs climb Makalu, it's also thanks to you. You can be proud of having climbed loads up to 26,000 feet. Throughout his story, he never ceases to highlight their qualities: courage, stamina, self-sacrifice, humour and, last but not least, their sense of service. "These are the real snowmen. They've been working for us for a month, unaffected by the weather, giving their all, ready for any kind of dedication, never complaining, pushing their capacity for resistance beyond the usual limits, with the sole aim of accomplishing the mission entrusted to them, with no other ambition. Our joy is theirs. Their role ends when there is nothing left to carry, which in the Himalayas means that the goal is near. And then they come back down, happy and singing. What a magnificent lesson!

The Sherpas, indispensable companions, photo from the book Makalu © Jean Franco

15, 16 and 17 May: the summit for everyone

On the morning of 15 May 1955, -32°C in the tents. Oxygen, used without counting the cost, including at night, gave them a restorative rest. They woke up at 5.30am. Sunny, no wind. In top form, Jean and Lionel climbed the six hundred and eighty-five metres to the summit at a steady pace. A final barrier of seracs to negotiate and a long sling of rising snow took them to the foot of the final mixed spur at 8,200 meters. It took them an hour to climb it, and forty-five minutes of easy progress on the summit snow ridge... They were there. Couzy: ‘The summit is extraordinary. It's the sharpest snow peak I've ever seen. Like the tip of a pencil. The snow ridge leading up to it is very thin.

Jean Couzy at the summit of Makalu, 15 May 1955 © Lionel Terray

On 16 May, it was the turn of Jean Franco, Guido Magnone (a genius handyman who often repaired oxygen inhalers) and sirdar Gyaltsen Norbu to climb to the summit. They were followed on 17 May by Jean Bouvier, Serge Coupé, Pierre Leroux and André Vialatte. It was the first and only expedition since the dawn of Himalayan climbing to see all its participants reach the summit. A masterstroke.

The entire team. Standing, left to right: Lionel Terray, Jean Bouvier, Pierre Leroux, André Vialatte, Guido Magnone, Michel Latreille, André Lapras, Abbé Pierre Bordet. Crouching, from left to right: Jean Couzy, Serge Coupé, Jean Franco.

Appendicitis at 5,000 metres

But the feat did not end there. Back at base camp, Sona, one of the Darjeeling Sherpas, was ill. Contractures, nausea, vomiting... Diagnosis: acute appendicitis. Doctor Lapras would like to be wrong. Twenty-four hours later, he had no choice but to operate. Midnight. Three aluminium camping tables, tied together, become the operating table. Ether was used as an anaesthetic. Franco, Bouvier, Coupé and Leroux improvised themselves as the surgeon's assistants. Gyalzen, the sirdar, acts as Sona's interpreter. Franco: ‘Gyalzen is green with emotion, ready to faint, the man from Mount Api who once carried his dying sahib over the snow of the summit ridge at 7,000 metres. He asks us to let him out". It's four o'clock in the morning when the doctor serves the last clasp. Sona will live.

Terray et Magnone : retour par le chemin des écoliers !

Terray and Magnone: back along the schoolchildren's route!

In his remarkable autobiography, Les conquérants de l'inutile (Conquerors of the Useless), Lionel Terray describes in just a few lines his return with Guido Magnone, via the schoolchildren's route. Lionel Terray and Guido Magnone were in top form on their descent of Makalu, and were amateur film-makers during the expedition. Eager to discover the Solo Khumbu, they obtained permission from Franco to separate from the group.

With a few porters, they reached Namche Bazar after a three-day walk. Terray: ‘For two days, there was nothing but singing, dancing and fraternal libations of millet beer and butter tea’. As major religious festivals were due to be held at the Thame gompa, they headed off to the monastery to see the unusual tantric religious dances. But they had to get back. Terray again: ‘an improbable path, crossing a pass at over 6,000 metres’ and a week's forced march took them to Kathmandu. Although no pass is mentioned, experienced travellers will easily recognise the route: Sherpani pass, West pass, Amphu Laptsa, Namche Bazar, Thame, Teshi Laptsa, Kathmandu!

Who can beat that?

Join us in April 2022 for an extraordinary adventure in Makalu

We will be guided in a small group by Serge Bazin, a French mountain guide who knows Makalu well, having already reached the summit at 8,485 metres. The approach is an 11-day trek via the Shipton's trail. Then comes the climb itself, which takes four camps. The main difficulty lies between camps II (6,600m) and III (7,500m). A long spur in mixed terrain, with no possibility of setting up an intermediate camp, requires excellent physical condition and the ability to abseil. A major summit, reserved for experienced mountaineers.

Read more about our ascent of Makalu guided by Serge Bazin.

And see below an animation showing the ascent of Makalu:

Expeditions Unlimited blog

Expeditions Unlimited blog