It had taken fifty-six years of intense effort to reach the summit of Kangchenjunga. First there was the first ‘High Route’ climbed by Douglas Freshfield in 1899. Then, in 1905, Aleister Crowley, a sulphurous magician, determined the correct route for an ascent of the south-western slope. In 1929 and 1931, the Germans unsuccessfully fought an exhausting and sometimes tragic battle on the north-east spur and the long north ridge. Finally, in 1955, it was the route initiated by Crowley that provided the key to success for the British team of George Band and Joe Brown. We take you back to those intense years.

See all our climbs above 8,000 meters.

Douglas Freshfield: 1899, seven weeks for the Kangchenjunga ‘High Route

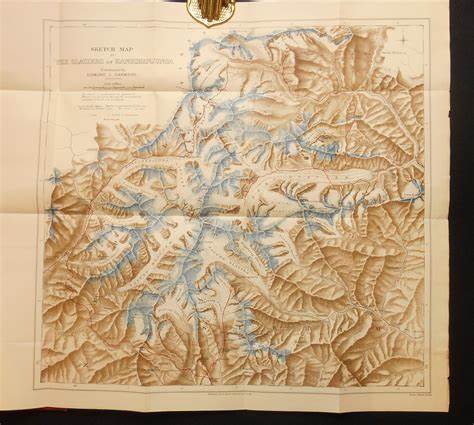

The remarkable map drawn up by Professor Edmund Johnston Garwood, a true work of art.

From Darjeeling, the English, masters of Sikkim, set their sights on the high peaks of Kangchenjunga, the easternmost giant of the Himalayas, 75 km away. As early as 1848, Sir Joseph Hooker approached the slopes of both sides, Nepal and India. In September and October 1899, the British explorer and mountaineer Douglas Freshfield, accompanied by Professor Garwood and the illustrious photographer Vittorio Sella, completed in seven weeks what can be described as the first ‘High Route’ to Kangchenjunga.

Setting off from Darjeeling, they headed due north, penetrating deep into the Zemu glacier, estimated to be almost 30 km long. This enabled them to approach the north-eastern slope, which looked promising. A long loop on the edge of Tibet ends with the crossing of the Jongsong La pass (6,045 m). They then followed the entire west face of Kangchenjunga. Freshfield believes it is also possible to find a route to the summit on this side. The return to India was via the Kang La pass (5,095 m) in the south of the massif. Seven weeks of exceptional trekking, unfortunately impossible to carry out these days because of the Indo-Chinese border dispute.

Kangchenjunga from Tonglu, India © David Ducoin

1905: A sulphurous occultist on the slopes of Kangch

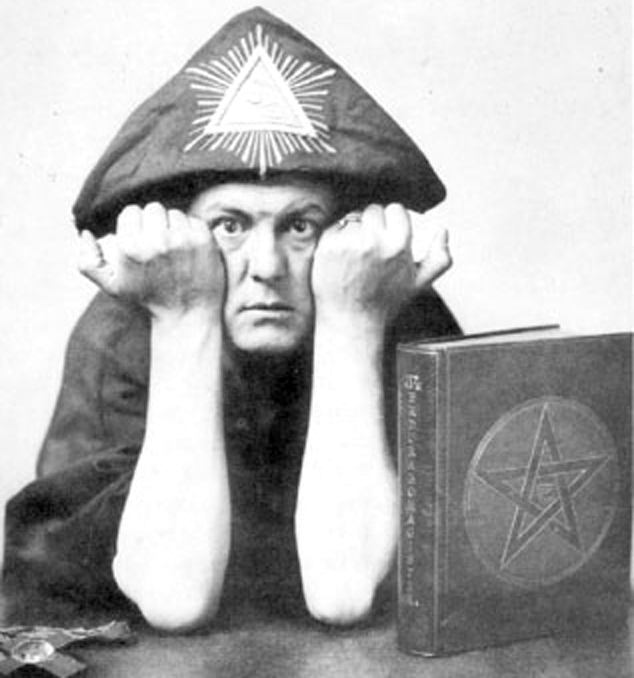

Of all the whimsical characters fascinated by altitude, few come close to Aleister Crowley, whose tortured personality we have already mentioned. After trekking the glaciers of the Karakoram in 1902, in the company of Swiss doctor Jules Jacot-Guillarmod, Crowley set off again in 1905, still with the doctor. But this time as expedition leader. At K2, Crowley took a long look at the south-east ridge. His conclusion: it was on this ridge that the key to the summit lay. A remarkable intuition, confirmed fifty years later. At Kangchenjunga, the ‘magician’ once again hit the nail on the head. Although the idea for the expedition to the then little-known south-western side of the mountain (the Yalung side) came from the doctor, Crowley must be credited with a remarkable premonitory vision. Despite the difficulties of the route, he was convinced that it was the key to success.

Aleister Crowley: the enigmatic and highly controversial ‘magician’, self-styled ‘The Great Beast 666’.

For the British Alpine Club he will be ‘the despicable Aleister Crowley’.

‘This is the kind of accident for which I feel no compassion’.

But if his intuitions prove to be luminous, his particular methods are another matter. Authoritarian, contemptuous of the porters and convinced of his superiority, he bosses everyone around. So much so that his expedition companions, led by Jacot-Guillarmod, mutinied and turned back at camp V at 6,220 m. On 1 September 1905, Crowley remained alone at the camp with Charles Reymond, another Swiss. Jacot-Guillarmod, the Italian de Righi and the Swiss Alexis Pache, accompanied by four porters, decided to descend to camp III. It was five o'clock in the evening. The heavy snow was a danger. Crowley warned them, but they ignored him. In the middle of the slope, one of them slipped and triggered an avalanche: Pache and three porters disappeared under the snow.

At the desperate cries of the survivors, Charles Reymond rushes in. Crowley, disdainful, stays in his tent. Crowley: ‘This is the kind of accident for which I feel no sympathy’.

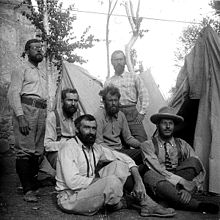

Jules Jacot-Guillarmod, Charles-Adolphe Reymond and Alcesti C. Rigo De Righi (left to right)

at the base camp of the Kangchenjunga expedition in 190

Jules Jacot-Guillarmod had to threaten to publish Crowley's erotic writings.

When he disembarked the next day, he passed by the survivors ‘without even asking about our missing comrades’, as Guillarmod put it. Crowley rushed back to Calcutta, gave his own version of events and took advantage of the situation to get his hands on the expedition's funds, which had largely been raised by Jacot-Guillarmod. It was only the threat of public exposure of his pornographic poems that got him to return some of the embezzled money. This put an end to his career as a himalayist... to the benefit of his esoteric activities. His attitude earned him the nickname ‘the despicable Aleister Crowley’ from the respectable British Alpine Club.

1929, the long struggle of the Germans on the north-east slope

In 1899, Douglas Freshfield, from the Zemu glacier, had put forward a favourable hypothesis by observing the north side of the mountain. To confirm this, Dr Paul Bauer led two German expeditions to the north-east spur. In the summer of 1929, with the monsoon season in full swing, his first expedition struggled to make its way, first through the dense undergrowth and then along the moraines, following the route initiated by Freshfield along the Zemu glacier. On 13 August, the base camp near the ‘Green Lake’ (5,050 m) was set up. After days of dangerous progress, they reached camp X at 7,020 m. On 3 October, two climbers, Allwein and Kraus, reached 7,400 m without difficulty. Victory seemed close. Unfortunately, the monsoon was still with us, burying them under two meters of snow in twenty-four hours. The retreat between the avalanches was a long ordeal lasting six days. They owed their lives to the fact that most of the camps were dug into the ice, forming providential caves. The return to the lower valleys, with its torrents in flood and landslides, gave them a few more scares.

The terrible ice fungi of the north-east spur © DAV/Deutsche Himalaja-Stiftung

1931, Bauer persists

In 1931, Bauer was back. Convinced that beyond camp X of 1929, the route would be easy. But on 9 August, Hermann Schaller and Pasang fell to their deaths just before camp VIII (6,270 m). Wounded, the team did not return to camp VIII until 24 August. Beyond that, ice towers and unstable ledges delayed progress. On 15 September, an ice cave served as camp XI at 7,650 m. On 17 September, Hartmann and Wien reached 8,000 metres. But the ridge plunged for 60 metres before suddenly straightening out. 150 metres of highly unstable snow still separated them from the north ridge. Hartmann: ‘At 600 metres below the main summit of Kangchenjunga and at a horizontal distance of 1,800 metres, we headed back’.

The Siniolchu ‘Most beautiful mountain in the world

As a consolation prize, on the way back they spotted the access route to Siniolchu (6,888 m), considered by Douglas Freshfield to be ‘the most beautiful mountain in the world’. In 1936, Paul Bauer and three other companions returned to climb it successfully.

.jpg)

The Siniolchu, ‘the most beautiful mountain in the world’ according to Douglas Freshfield.

1954, British recognition

The Second World War put a temporary end to attempts to discover the ‘Kangch’, as it came to be known. In 1951, 1953 and 1954, three reconnaissance trips followed one another. First in small groups, then in a real caravan. The Anglo-Saxons, after their recent victory on Everest in 1953, were feeling their wings grow. Their objective: to ascend the 20-kilometre-long Yalung glacier, then explore the eponymous slope, suggested by Freshfield in 1899 and already partially traversed by Crowley in 1905. Led by John Kempe, the 1954 expedition reached an altitude of 5,790 metres of altitude, largely surmounting the icefall that blocked the lower part of the route.

Joe Brown ‘The Human Fly

In 1954, Don Whillans and Joe Brown burst onto the scene from a working-class background, at the very opposite end of the very select Alpine Club. Simple plumbers by trade, these two brilliant British climbers climbed the Aiguille de Blaitière in Chamonix. They climbed an extremely difficult crack that Gaston Rébuffat, in his ‘100 plus belles courses’, described as ‘a vertical crack with smooth edges and bottom (VI, very athletic)’. Joe Brown earned the nickname ‘the human fly’. His success earned him a place on Charles Evans' expedition to Kangchenjunga the following year. At 24, Brown was the youngest member of the team.

1954, reconnaissance Britannique

La seconde guerre mondiale met provisoirement fin aux tentatives sur le “Kangch” comme on l’appelle désormais. En 1951, 1953 et 1954, trois reconnaissances se succèdent. D’abord en petit comité, puis en véritable caravane. Les anglo-saxons, après leur récente victoire à l’Everest en 1953, se sentent pousser des ailes. Objectif : remonter le glacier de Yalung, long de 20 kilomètres, puis explorer le versant éponyme, suggéré par Freshfield en 1899 et déjà partiellement parcouru par Crowley en 1905. Menée par John Kempe, l’expédition de 1954 atteint l’altitude de 5 790 m, surmontant en grande partie la cascade de glace qui barre la partie inférieure de l’itinéraire.

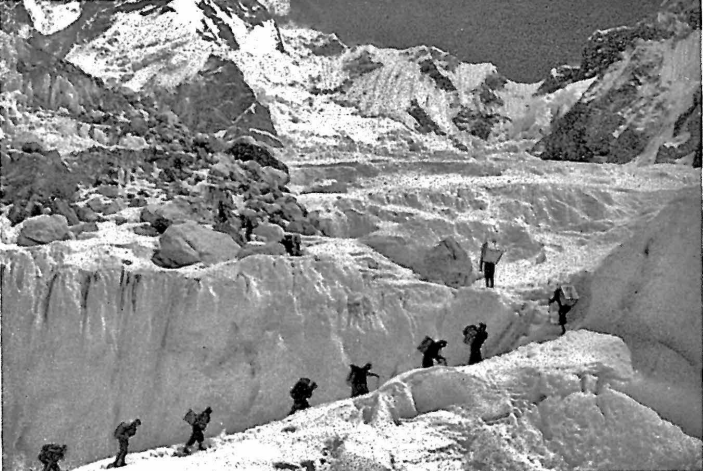

The route as a whole, photo taken during the attempt to climb Yalung Peak © Georges Band

On 22 April, the British realised that the route they had initially chosen would be impassable for the Sherpas. A new attempt on the left-hand branch proved successful. On 4 May, camp 3 (6,650 m) was set up at the base of the second icefall. This leads to the vast glacial plateau ‘The Great Shelf’, which stretches between 7,160 and 7,770 m, at the foot of the upper part of the south-west face. There are another 1,500 meters to the summit. Three more camps are needed and here they are at the sixth, at 8,200 meters.

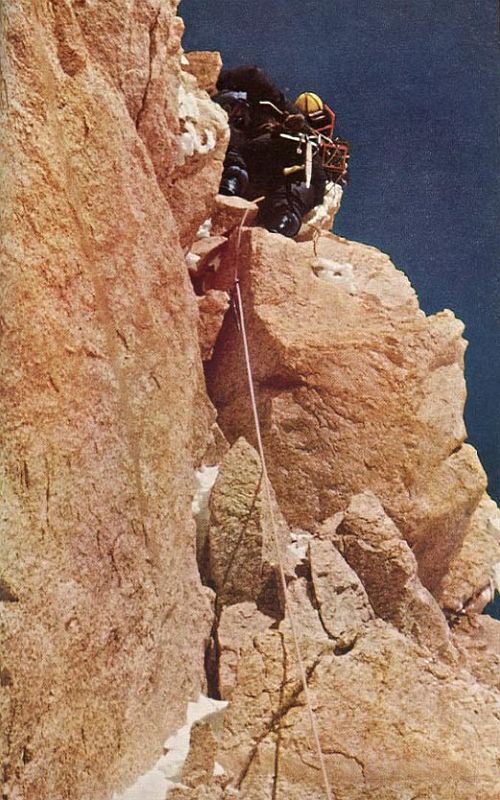

In the upper icefall

Consecration for George Band and Joe Brown

24 May 1955, the wake of arms. George Band and Joe Brown, precariously balanced in a tent erected on a narrow bench, drew straws to see who would sleep half in the air! To be on the safe side, they spend the night roped up.

They wake up at five o'clock. At 8.30am, they were on their way to glory. The route, between bands of rock and small corridors of snow and ice, is not easy. They even had to climb back down a few meters, wasting an hour and a half of their precious time and oxygen. They finally reached the west ridge leading to the summit. Joe Brown led the way, without crampons, through some difficult rocky passages.

At 2.30pm on 25 May 1955, they came to rest on a platform less than ten meters from the summit (8,586 m). In keeping with the promise they had made to the Sikkim authorities, the abode of the Gods was thus respected. Band: ‘I'm glad I didn't leave any footprints on the summit’. Georges Band, then aged 26, was the youngest member of the victorious Everest expedition in 1953.

Georges Band under the summit

The last crack before the summit © Charles Evans

The following day, May 26 1955, Norman Hardie and Tony Streather repeated the feat. Meanwhile, at base camp, Sherpa Pemi Dorjee died of altitude edema, tarnishing this magnificent success.

A high-class human adventure

A model of its kind, this great human adventure saw everyone do their part without complaining. Masterfully led by Charles Evans, the expedition owes its success to the systematic use of oxygen, both night and day, from an altitude of 7,000 meters.

Today, the classic ascent of Kangchenjunga is via the 1955 route. While the technical difficulties are less than on K2 and Nanga Parbat, the danger of avalanches is greater. This is particularly true on the ascent to camp 1 and on arriving below camp 2 at the summit of the lower icefall.

Thus, in the three years from 1953 to 1955, the three highest peaks on the planet gave way to the conquest of Himalayan climbers: Everest, K2, and finally Kangchenjunga.

Expedition to Kangchenjunga with Expeditions Unlimited

Find out more about our next ascent of Kangchenjunga to 8,586 meters.

See below the animated itinerary for the ascent of Kangchenjunga:

Text and animation by Didier Mille.

Climb Kangchenjunga at 8586 meters in Nepal

Climb Manaslu at 8163 meters in Nepal

Expeditions Unlimited blog

Expeditions Unlimited blog