Ever since the first climbers set eyes on the towering summit of K2, the mountain has fascinated. Firstly by its shape, an almost perfect pyramid, two Matterhorns piled one on top of the other. Then for its difficulties: verticality reigns supreme. Only the best can aspire to its ascent. 1902 saw the first attempt, by Aleister Crowley and Dr Jules-Jacot Guillarmod. 119 years later, on 19 January 2021, Nepalese climber Nims Dai successfully completed the first winter ascent. And without Ox, please! Nine other Nepalese succeeded alongside him. 119 years of struggles, tragedies and feats of all kinds. Here's an anthology of some of the highlights.

Conway and Eckenstein, the forerunners

We have already recounted the discovery of K2 by Lieutenant Thomas George Montgomerie in 1856 and the measurement of its altitude by Lieutenant Henry Haversham Godwin Austen in 1860. Then came the arrival of the first mountaineers, Sir Martin Conway accompanied by a certain Oscar Eckenstein, a great peak climber in the Alps.

Black magic on the slopes of K2

But the story really begins in 1902. A disparate expedition, led by... Oscar Eckenstein, was seriously considering tackling K2. During a trip to Mexico in 1900, Eckenstein met a colourful eccentric: Aleister Crowley, a mountaineer, poet, freemason, heroin addict, occultist, magician and even a practitioner of black magic... Six mountaineers in all, including Dr Jules Jacot-Guillarmod, a Swiss doctor. With Eckenstein ill, Crowley (1) set off with Jules Jacot-Guillarmod to tackle the north-east ridge. They reached an altitude of 6,600 meters. Dr Jacot-Guillarmod took the first exceptional photos of the Baltoro glacier.

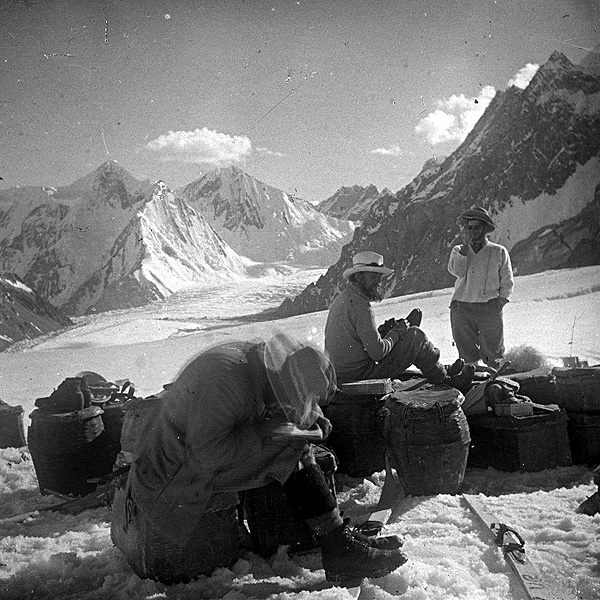

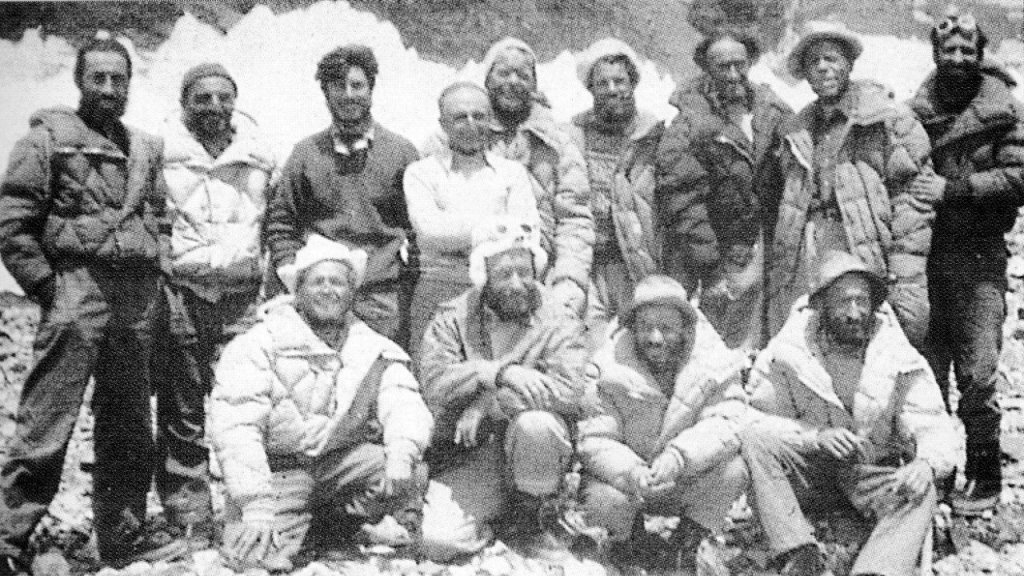

The 1902 base camp © Jules Jacot-Guillarmod

1909: the Duke of Abruzzo leads the way

Prince Louis Amédée of Savoy, Duke of Abruzzo, was not content with the luxuries of the court. In 1897, he made the first ascent of Mount Saint-Elias (5,589 m) in Alaska. In 1906, a polar expedition to the North Pole cost him two fingers, amputated due to frostbite. In 1906, he climbed 16 peaks in the Ruwenzori mountain range (present-day Uganda, at the time of the British protectorate). Finally, in 1909, he set out to climb K2. He chose the south-east ridge, which appeared to be the most direct route to the summit. However, the excessively steep slopes and rocky passages soon brought progress to a halt, at 6,250 meters, just above today's Camp I. But the name of the route was immortalised: the Abruzzo ridge.

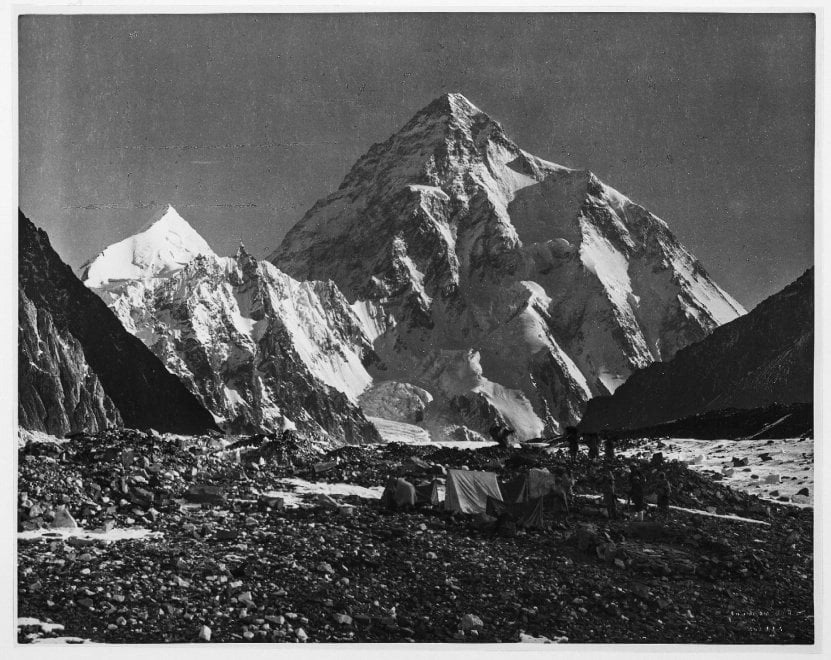

K2 seen from the base camp in 1909 © Vittorio Sella

1929: the first steps of Ardito Desio

The crowned heads of the day were not shy. Twenty years after his uncle Louis Amédée of Savoy, Prince Aimone, Duke of Aosta and Spolete, launched an exploration campaign in the Karakoram. Ardito Desio (32), professor emeritus of geography and geology, was one of them. Greatly impressed by K2, he vowed to return: the summit would be Italian.

The first three serious attempts: all American

1938: Bill House, the man with the chimney

It was the Americans who fought the longest to succeed. In 1938, Charles Houston led the way. Taking up the route of the south-east ridge, opened by the Duke of Abruzzo, and better equipped, the mountaineers progressed to the foot of a thirty-five meters chimney, one of the most difficult lengths of rope ever climbed at such an altitude. Bill House (24), roped up with Robert Bates, climbed the now eponymous ‘House Chimney’. Further on, in the slopes above the ‘Black Pyramid’, difficult mixed terrain awaited the climbers. After a final attempt at 7,800 metres, Houston and Petzoldt turned back, exhausted, fearing the arrival of bad weather... which never came. The first missed opportunity?

1939: Fritz Wiessner's eternal regrets

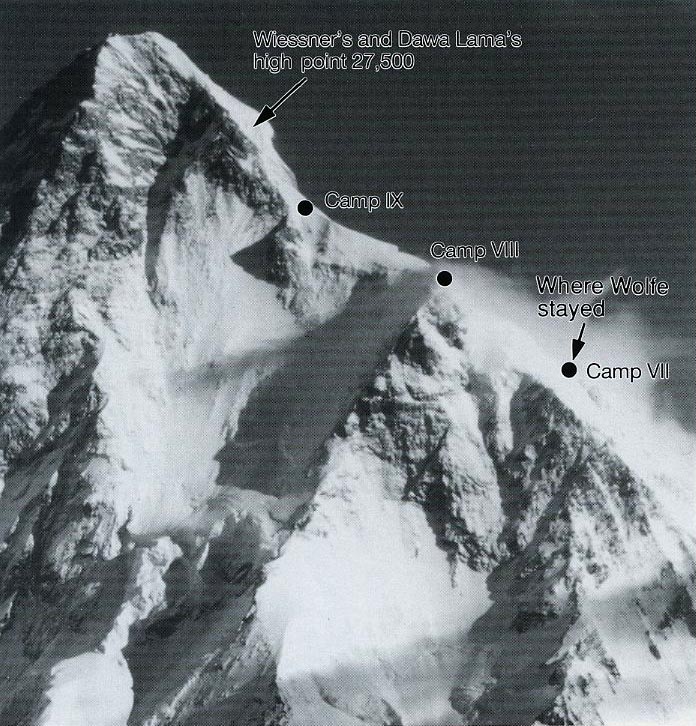

Of all the expeditions, the one that came closest to succeeding, and without oxygen, was that of 1939. The expedition was led by Fritz Wiessner, a German naturalised American, and Sherpa Pasang Lama. On 19 July, well beyond Camp IX (7,940 metres), they climbed to 8,365 metres, without oxygen or radio sets. To reach the summit ridge, they had to climb less than ten meters across icy rock. Night fell, there was no wind and the moon was full. The summit is there, within reach. But the Sherpas fear the demons of the night.

The highest point reached by Wiessner and Pasang Lama, probably to the left of the Bottleneck,

today's key passage to the summit. Unknown

Understandably, Wiessner relented: they would return tomorrow... A fatal error. Exhausted by the altitude (they had just spent four nights at 7,600 metres of altitude, without any oxygen), they retreated. Pasang Lama lost his crampons: he would never be able to climb again. What followed was a tragedy. With Pasang Lama and Dudley Wolfe (2), who had climbed to camp VIII and was the only mountaineer still standing, they began the long descent to base camp. Due to a lack of communication (the cruel absence of radio sets), and believing the climbers to be dead, all the intermediate camps had been emptied: no more sleeping bags, no more stoves, no more food. It was impossible to stop. Wolfe, following an unfortunate fall, had to stay at camp VII (7,500 m). He never climbed down again. Despite a heroic rescue attempt by three men who climbed up from the base camp to help him. The Sherpas Pasang Kikuli, Pinsoo and Kitar, along with Dudley Wolfe, were the first four victims on K2. Wiessner would regret giving in to Pasang Lama for the rest of his life.

1953: Charles Houston, the wild mountain

In 1936, at Nanda Devi, food poisoning forced him to abandon the last camp. In 1938, K2 also eluded him. After Bill House, Wiessner proved that the summit was within reach. But on K2, courage, talent and self-sacrifice are not enough. You also need luck. The weather is more unstable than in Tibet. And weather routers don't yet exist.

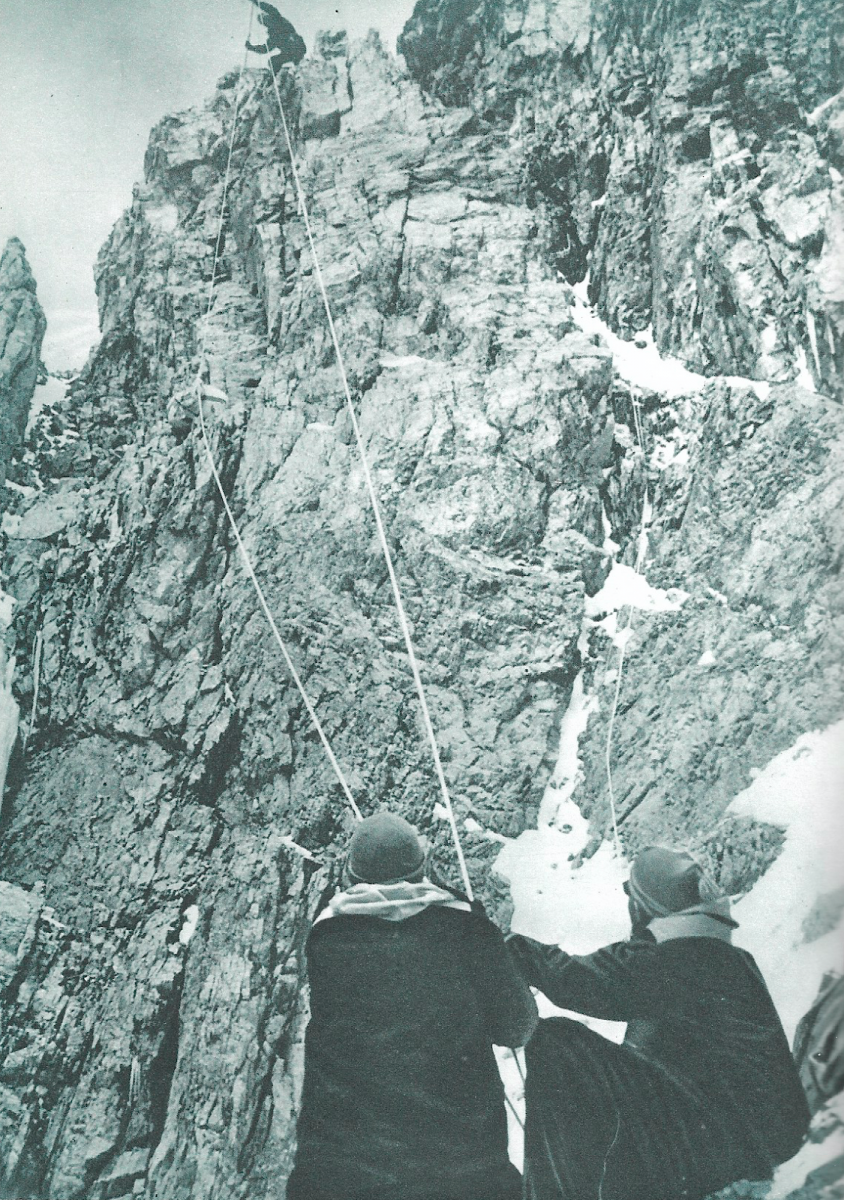

The cable car installed to carry loads up the Chimney House © Charles Houston-Robert Bates

A storm, the likes of which can only be found on K2, left the American climbers stranded for 10 nights at Camp VIII, at an altitude of 7,800 metres of altitude, at the beginning of August. There were eight climbers, without Sherpas (Pakistan, jealous of its prerogatives, refused them access), huddled together in two small tents. One of them, Art Gilkey (27), suffering from thrombo-phlebitis, had to be evacuated urgently: an embolism at this meters of altitude would be fatal. His companions tried the impossible. They put him in a makeshift sledge and lowered him down by rope. At first, an avalanche almost took the whole team with it. A little later, one of them fell, dragging his rope-mates down with him. In extremis, Pete Schoening (26), the youngest in the group, stopped the other five from falling. Bates: ‘Three separate ropes tangled together to save the lives of five men’.

Saved? Art Gilkey, immobilised on his sledge while the others set up a makeshift camp, disappeared, probably swept away by a snowfall. Houston wrote: ‘It is by surpassing his powers of endurance that man learns to know himself’.

Robert Bates and Charles Houston's account of the expedition, The Savage Mountain, was to have the same impact on the English-speaking world as Maurice Herzog's book Annapurna, premier 8 000 in France.

The Art Gilkey memorial now stands at the foot of K2. The list of climbers who have died on the Earth's second highest peak is long.

1954: Italian victory, between glory and betrayal

Of all the great first ascents of one of the fourteen eight-thousanders, none has generated so much lasting controversy. Except for the victory on K2. The British climbed Everest in May 1953. The Germans conquered Nanga Parbat in July of the same year. The disastrous American expedition in August 1953 clipped Uncle Sam's wings. Who will conquer K2?

1954. Italy, emerging from the Mussolini era, needed to restore its image on the international stage.

Professor Ardito Desio, now aged 57, still dreamt of offering his country this victory. So, under the aegis of the Italian Alpine Club and the benevolent gaze of the Italian government, a major expedition was organised. Eleven climbers, with no experience of the Himalayas, were brought together. Among them was the youngest, the dashing Walter Bonatti (24), a rising star in mountaineering, and two other brilliant climbers: Lino Lacedelli (29) and Achille Compagnoni (40). Ardito Desio conceived the project as a military expedition, totally subordinate to the decisions of the ‘leader’. An excellent organiser, he was not a mountaineer. Governance in high-altitude camps is based on ‘memos’! But nothing was left to chance, in particular the supply of oxygen cylinders, deemed essential to success.

The whole team at the base camp © Unknow

Eight camps have been set up. From camp VIII, set up at 8,000 metres, Achille Compagnoni and Lino Lacedelli had to set up a final camp IX, before setting off for the summit. Walter Bonatti, the fittest of the group, and Amir Mahdi, a sturdy Pakistani porter, were responsible for a long portage between camp VIII and camp IX to provide the oxygen essential for victory. But the two would-be victors certainly remembered Hermann Buhl's solitary feat on Nanga Parbat the previous year. Refusing to obey the leader, he succeeded alone and without oxygen. Could Bonatti do the same and steal the show?

To be on the safe side, they set up camp IX higher than planned, beyond a barrier of icy slabs, impassable at night. Bonatti and Mahdi climbed laboriously. They would never reach the camp. In a brief verbal exchange, Lacedelli asked Bonatti to put down the bottles and go back down to camp VIII. Too late, it was dark. They had no tent, no sleeping bag, no stove.

Bonatti had no alternative but to dig a tiny platform in the very steep slope and wait there for daylight. Mahdi loses half his mind. Miraculously, both survive, Madhi with severe frostbite, Bonatti psychologically scarred for life. Bonatti: ‘That night, I should have died’. The next day, Compagnoni and Lacedelli went down to get the bottles and then climbed to the summit, thanks to the oxygen. The official story is that the cylinders were used up in the last five hundred metres of ascent to the summit. K2 was climbed ‘without oxygen’!

.jpeg)

On the left. Achille Compagnoni at the summit of K2 © Lino Lacedelli

On the right. Walter Bonatti on his return from K2 © Walter Bonatti

The Bonatti affair

The story itself isn't exactly glowing. Back at the base camp, an apology to Bonatti might have been enough not to tarnish the glory of the victors. But the worst was yet to come: Bonatti discovered, in a sensational newspaper article, that Compagnoni was spinning a web of lies. The two winners had arrived at the summit without oxygen, the bottles having been partially used during the night by Bonatti and Mahdi during the bivouac. Problem: Bonatti and Mahdi had no regulators. Compagnoni and Lacedelli were the only ones who did. Compagnoni added lies and slander to the infamy.

What followed was a controversy worthy of ancient tragedies. The CAI (Italian Alpine Club) only agreed to review the official version in 2004, after the death of Professor Desio (2001). As for the winners, they were showered with praise. Necessity is better than right.

16 January 2021, 3pm: first winter ascent of K2 for the Nepalese, a great collective story

In contrast to this sad adventure, where personal egos largely prevailed, the first winter ascent by ten Nepalese himalayists will also go down in history. Two teams, who could have been total rivals, joined forces on the mountain to tackle the ultimate challenge: K2 in winter. The result was that, ten metres below the summit, the Nepalese teamed up to take the final steps together. Among them was Nirma Purja, nicknamed ‘Nims Dai’, the man who climbed fourteen 8000m peaks in six months (and six days). This giant even went so far as to climb K2 ‘without Ox’. A fine lesson in humility.

We invite you to climb K2, the grail for highly experienced himalayists.

We are attempting to climb K2 ‘the wild mountain’, the second highest summit on earth and the culmination of a career as a Himalayan climber. This expedition has all the hallmarks of an ultimate challenge. The altitude, of course, but above all the almost unique verticality of such a mountain and the technical difficulties. With the exception of the ascent between camps 3 and 4, which takes place on slopes that could be described as gentle, most of the time you will be climbing between 40 and 50°, with a large number of mixed level III to IV passages, which represents a considerable gradient when all other factors are taken into account. Three key passages punctuate the route, and these technical difficulties are compounded by capricious weather. Attempting to climb K2 requires perfect self-control, as well as real experience of progression, both on the way up and on the way down, along fixed ropes. You also need to know yourself well, and how far you can push yourself. Because on the K2, more than anywhere else, reaching the summit is only half the battle.

Expeditions Unlimited offers you climb K2 at 8611 meters in Pakistan.

Below is the animated itinerary for the ascent of K2 :

Text by Didier Mille.

___

1. Taken from Aleister Crowley's own account. Other sources indicate Wiessely and Jacot-Guillarmod.

2. In 2002, the remains of Dudley Wolfe were identified at the base of K2, along with pieces of his tent. The three Sherpas probably disappeared in the storm, unable to reach him.

Climb K2 at 8611 meters in Pakistan

Climb Broad Peak at 8047 meters in Pakistan

Expeditions Unlimited blog

Expeditions Unlimited blog