The 1938 expedition was the last to be led by the British on the north face of Everest. The conquest of the poles eluded them. The French, their long-standing adversaries, took the first 8,000 m ascent from them. That's all they need. Now they have to climb Everest. Expeditions Unlimited and Didier Mille are delighted to bring you this second instalment in the saga of the first ascent of the roof of the world.

See all our climbs above 8,000 meters.

1947-1953: The final race

Tensing Norgay: "It is impossible to reach Everest via Nepal".

July 1947: Swiss expedition to Kedar Dome (6,940 m), in the Garwhal Himalayas. Following an accident involving the Sirdar (head of the porters), André Roch, leader of the group, did not hesitate to entrust Tensing with this essential role. On 11 July, alongside André Roch, Tensing achieved his first summit in the Himalayas. It was a memorable day: he earned his stripes for Everest.

Tensing Norgay holds a record. Four successive summits of Everest from the North face. Three of them major, one clandestine. In the spring of 1949, with a stubborn Canadian, Earl Denman, they painstakingly reached the lower slopes of the North Col.

Tensing then sent a final letter to Denman in which he summed up the spirit of the times: "There is a road to Everest. It is the Tibet route. Through Nepal (...) the track would be too steep and too narrow. It is impossible to reach Everest through Nepal.

The same year, the Nepalese Prime Minister timidly authorised the first small British exploration. The Langtang valley, near Kathmandu, was to be the scene. Fifteen kilometres north of Langtang stands the Gosainthan or Shishapangma massif (8,027 m). The smallest of the 8,000, it has not yet been mapped.

The indefatigable Bill Tillman couldn't miss this dream opportunity. Peter Lloyd, a fellow climber on the 1938 Everest attempt, followed him. Tensing Norgay, back from Everest with Denman, got the part of Sirdar. From week to week, during the monsoon season, they climbed all the passes and glaciers in the upper Langtang valley. The crossing of Tilman's pass, linking Langtang to the Jugal Himal, remains today a major trek, part of our Grande Traversée du Népal.

View of Mount Shishapangma from the Langtang valley

View of Mount Shishapangma from the Langtang valley

1950: the southern slope unveiled

A palace revolution in Kathmandu, the end of the Rânas dynasty. The new government, worried about events in Tibet, opens its doors wide to Westerners. The French obtained permission to leave for Dhaulagiri (they eventually climbed Annapurna on 3 June 1950). The British rushed to the enigmatic south face of Everest, known only from Mallory's observations at Lho La in 1921.

On 29 October, with new companions, Bill Tilman left Jogbani on the Indian border, heading for the Khumbu, then Terra Incognita. Alongside him were Dr Charles Houston (who had won the Nanda Devi with him in 1936), his father Oscar (the financier of the operation) and two friends: Anderson Bakewell, a Jesuit by profession, and... Betsy Cowles. For Tilman, an irritating female presence!

Coming from the south, they took a route that has now been abandoned (because of access via the Lukla altiport) along the Arun river and reached Namche Bazar on 14 November: Tilman's Mecca. Barely thirty houses with whitewashed facades.

At the Tengboche monastery, Tilman and Charles Houston continued on their own. Their three companions stayed with the lamas. Everest lay hidden in the clouds.

Finally they reach a point from which they can see the lower part of the famous Khumbu Icefall. They climb Kala Patthar to get a clear view. But the summit of the icefall, hidden by the Nuptse, escaped their view, as did the South Col. They were reduced to speculation. Tilman, in view of the steepness of the South Ridge, even doubted that Everest could be climbed from this side, echoing Mallory's view after his passage to Lho La in 1921.

Conclusion: further reconnaissance is needed, to try to access the West Combe and dispel the doubts.

Icefall in Khumbu

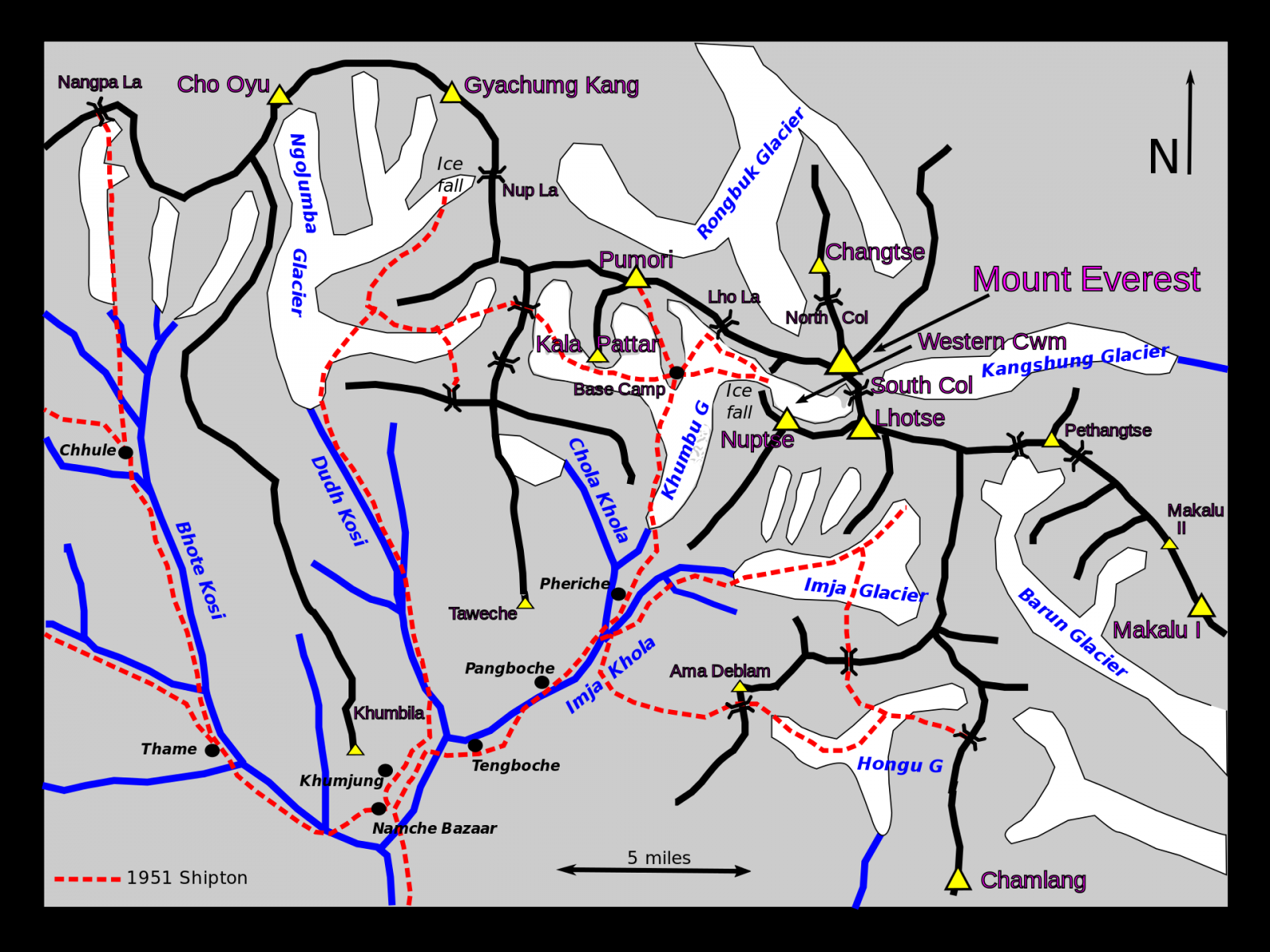

Reconnaissance in 1951: the British find the way

In 1951, to the great displeasure of the British, the Nepalese established a "rotation" for access to Everest: the British in 1951, the Swiss in 1952, the British again in 1953, the French in 1954 and the Swiss again in 1955.

Eric Shipton was entrusted with leading the 1951 reconnaissance expedition. Four Britons and two New Zealanders, including Edmund Hillary, took part. Sirdar was the legendary Ang Tharkay. Surprisingly, Tensing Norgay was not part of the team.

Following Tilman's observations, Shipton set the chances of finding access to the summit of Everest via the south face at 30%. But he was enthusiastic about the idea of exploring the Khumbu, the land of the Sherpas.

On 22 September, still from Jogbani, they reached Namche Bazar after a tough walk in the monsoon, bitten by leeches. They climbed to an altitude of 6,100 metres on the southern ridge of Pumori (610 metres higher than Tilman and Houston). They were finally able to see the summit of the Khumbu Icefall, the South Col between Lhotse and Everest and the South-East Ridge, the key to the ascent. The major question remained: how to cross the formidable barrier of seracs and reach the West Combe. They set off, laboriously making their way through the icy labyrinth. As they neared the summit, an avalanche forced them to turn back: Shipton didn't want to risk an accident that would halt any further attempts. There was too much snow, so they decided to come back later and explore the upper Khumbu.

For three weeks, they crossed all the major passes now used by trekking groups. On 28 October, they were back at the foot of the glacial maze. No such luck. In the last few metres leading up to the West Combe, a huge crevasse blocked the entire glacier, making it impassable in its current state. They set off again, but Shipton was convinced that he had identified the right route to succeed.

Routes to Mount Everest

Routes to Mount Everest

Time for the Swiss

Spring 1952: before the monsoon

From 13 March to 11 July 1952, André Roch led the first Swiss expedition to Everest. Raymond Lambert, an experienced climber, played a key role. Tensing Norgay joined the group, this time not only as Sirdar, but also as a member and climber in his own right. A Nepalese on a par with the "sahibs": never seen before.

Departure from Kathmandu on 29 March. A long route of tough ascents and descents leads to Lukla, then Namche Bazar. On 20 April, they set up base camp at Gorakshep. On the 25th, they began the ascent of the Icefall. In four days, they were at the foot of the great summit crevasse. An informed man is worth two. Eric Shipton had described the passage and they were ready to tackle it. Jean Jacques Asper, one of the climbers, descended into the crevasse, reached the opposite lip on a snow bridge and, after a difficult climb, finally got his footing in the west combe. The path to the summit had just opened up.

On 11 May, Camp VI stood at 6,900 metres, below the face of Lhotse. Shipton had advised a long ascent traverse to the South Col. They chose a much more direct route from camp V, the Genevois spur. Too steep, it did not allow them to set up intermediate camps. An exhausting climb. They had hoped to reach the Col Sud in a day from camp V. In the end, they had to set up an improvised bivouac two-thirds of the way up the slope. On 26 May, they finally set foot on the South Col at 7,906 metres, battered by terrible winds. Tensing Norgay made three shuttles between this camp and the bivouac to bring the equipment. A real feat! On the morning of 27 May, he set off again with Raymond Lambert in the hope of setting up a makeshift camp higher up on the south-east ridge. At an altitude of 8,400 metres, he bivouacked in a tiny tent. No sleeping bag, no stove, no food and a very limited oxygen supply. The following day, 28 May, they climbed for another five-and-a-half hours to reach an altitude of 8,600 metres, running out of strength and oxygen. Another 150 metres and they could have reached the South summit, and why not the main summit?

Would they follow a tragic destiny, similar to that of Mallory and Irvine, or continue to live? They chose to go back down. Tensing Norgay had just completed his fifth attempt.

Tensing Norgay and Edmond Hillary

Autumn 1952: after the monsoon

From 28 August to 31 December 1952, the people of Geneva went back into action. For the first time, after the monsoon. Among the participants were Raymond Lambert, of course, but above all Tensing Norgay, and the two men began a deep friendship. Nice cold weather at the base camp. The team climbs the West Combe. Unfortunately, on the slopes below Lhotse, a block of ice came tumbling down. It killed one porter and three others were injured when they came to his aid. Nevertheless, on 19 November, the South Col was reached. Unfortunately, the fierce wind and dreadful autumn cold forced them to abandon the climb. This was Tensing's sixth attempt.

1953 British expedition: 8,848 metres, perseverance finally rewarded

8,600 metres. The final point reached by the Swiss. The British knew: they had to win in 1953, or lose "their" mountain. Shipton, despite having climbed Everest five times, was judged to be too timid because he was too purist (he was reluctant to use oxygen), and was removed from the supreme command. John Hunt, an experienced mountaineer but above all a brilliant military man who knew how to organise and galvanise his men, was preferred to him. Ten men accompanied him. Dr Charles Evans and Thomas Bourdillon, a force of nature, formed an assault team.

Edmund Hillary, whose stamina and tenacity impressed Shipton on Cho Oyu in 1952, and of course, the inescapable Tensing Norgay, Sirdar but also a top climber, make up the other team.

The British team on the 1953 expedition

The end justifies the means. All the technological resources of the time were put to use. Footwear specially designed for high altitude, sleeping bags with double envelopes, special clothing, stoves tested by the Royal Air Force, aluminium ladders for crossing crevasses. But above all, two types of oxygen apparatus weighing 21 and 19 kilos respectively. And this time, the precious gas would be used even at night, to sleep in the high-altitude camps.

Hunt had learnt the lessons from the successive failures of all the previous attempts: the roped parties had failed to reach the summit because they had set off too low, too far. A camp had to be set up very high up, as close as possible to the South Summit (8,750 m).

On 28 May 1953, Camp IX stood at an altitude of 8,600 metres. Hillary and Tensing slept there on oxygen. In the morning, at 6.30am, they set off under clear skies, free of wind at last. At 9am, they reached the South summit, which had been climbed a few days earlier by the Evans-Bourdillon team, who had started from the South Col. They climbed slowly, but without difficulty, along the south-east ridge towards the summit. At an altitude of 8,780 metres, a very steep rocky passage a dozen metres high interrupts their progress: the "Hillary step". Hillary, who stands 1.90 metres tall and has been trained to carry heavy loads since he was a child, gives it his all to overcome this passage. IV at this altitude, with 20 kilos on his back!

29 May 1953, 11.30am: the two men stood on the highest peak in the world. The same day, Elizabeth II was crowned Queen of England. Edmund Hillary gave her the greatest gift of all. Beside him, Tensing Norgay, winner after seven attempts, carried the pride of Asia on his shoulders. Is he not the real hero of this saga?

Read the first part: The conquest of Everest: 50 years to reach the roof of the world - Part 1.

.jpg)

Tensing Norgay et Edmond Hillary

![]()

Edmond Hillary au sommet de l'Everest

Join the next Everest climb via the Nepalese South Face or the North Tibet side.

Sir Edmund Hillary : the race for Everest - 59 minutes

Expeditions Unlimited blog

Expeditions Unlimited blog