June 11, 1938. Eric Shipton, Bill Tillman and Peter Lloyd descend from Camp VI to an altitude of 8,300 meters. The seventh attempt to climb Everest, via the North Face, failed again. Since 1921, British mountaineers, masters of the terrain and without rivals, have been throwing all their energies into this ultimate conquest. Courage, self-sacrifice and obstinacy were not enough. The Sherpas, without whom nothing could be achieved, first as simple porters and then as inseparable high-altitude companions, played an active role. Two of them became legendary: Ang Tharkay and Tensing Norgay. Expeditions Unlimited looks back on this fantastic adventure, which we will share with you in spring 2021.

See all our climbs above 8,000 meters.

1903-1947: reconnaissance and first attempts

August 15, 1947, midnight. British India becomes India, where Hinduism will have to shape a nation. The Muslims of the Indian subcontinent also gained a homeland: Pakistan. After 350 years of undivided rule (1600-1947), the British lost their monopoly on all their activities.

This geopolitical fracas reverberated all the way to the highest peak on earth: Everest. From 1903 to that fateful night in 1947, only the British were allowed to launch expeditions to conquer the roof of the world. Everything belonged to them, right down to the very name of the mountain.

Chomolungma in Tibetan, or Sagarmatha in Nepalese? Que nenni. Originally known as Peak XV, its measured altitude of 29,000 ft (8,839 m), established in 1852 by the Survey of India (the Calcutta-based geographic department of the East India Company), makes it the highest peak in the world. Sir Andrew Waugh, then Director of the Survey of India, named it after his predecessor, Sir Georges Everest.

Once the mountain had been named, it remained to climb it, the ultimate challenge for the masters of the world at the time.

The first challenge was to reach the foot of this inaccessible mountain. At the dawn of the 20th century, the influence of the British Raj came to an end at the foot of the Himalayan barrier. Tibet did not allow foreigners to enter, and neither did Nepal, then under the Hindu dynasty of the Rânas.

In 1903, Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Francis Younghusband was ordered to negotiate a border dispute between the small kingdom of Sikkim, at the northeastern tip of the Empire, and Tibet. Exceeding his orders, he crossed the border and reached Lhasa. En route, two of his officers, Major Ryder and Captain Cecil Rawling, explored the Tibetan plateau and came within 90 kilometers of Everest.

The First World War put an end to any further attempts at exploration.

By 1919, Anglo-Tibetan relations had eased. At the end of 1920, the Tibetan government agreed to a first reconnaissance expedition. Two prestigious institutions, the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club, founded the Everest Committee and appointed Sir Francis Youghusband as its chairman. History was made.

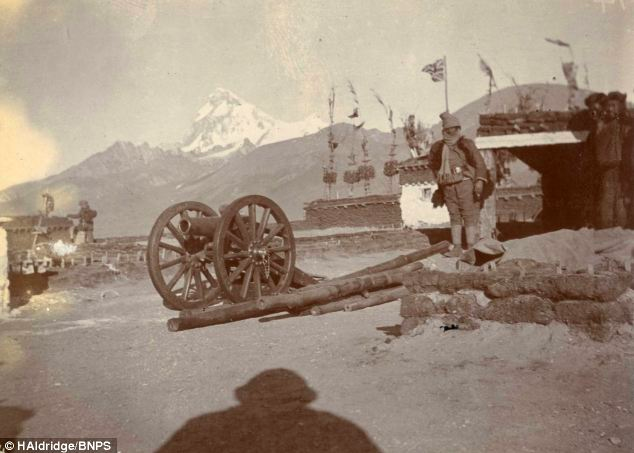

Youghusband Expedition 1903-1904, British camp, the Union Jack floats in front of Everest

Youghusband Expedition 1903-1904, British camp, the Union Jack floats in front of Everest

1921: Mallory takes his first steps on Everest

The objective of the first official reconnaissance: to reach the foot of the mountain. But it takes a keen mountaineer's eye to spot a possible ascent route. Georges Leigh Mallory, then aged 35, was entrusted with this important mission. Since the age of 17, he had been climbing glaciers in the Alps and English rock faces, and had built up a reputation as an excellent mountaineer. Everest was to captivate him. This mission sealed his destiny.

In 1921, the only route into Tibet from India starts in Darjeeling, crosses Sikkim, crosses the Jelep La (4,267 m) and descends the Chumbi valley, on the present-day border between Bhutan and Sikkim. It then passes the foot of the north face of Chomolhari, before turning due west towards distant Tingri. 480 kilometers: today's trekkers pale into insignificance!

The team left Darjeeling on May 18, 1921 and returned on October 25, after six months in the icy solitudes of the Tibetan plateau.

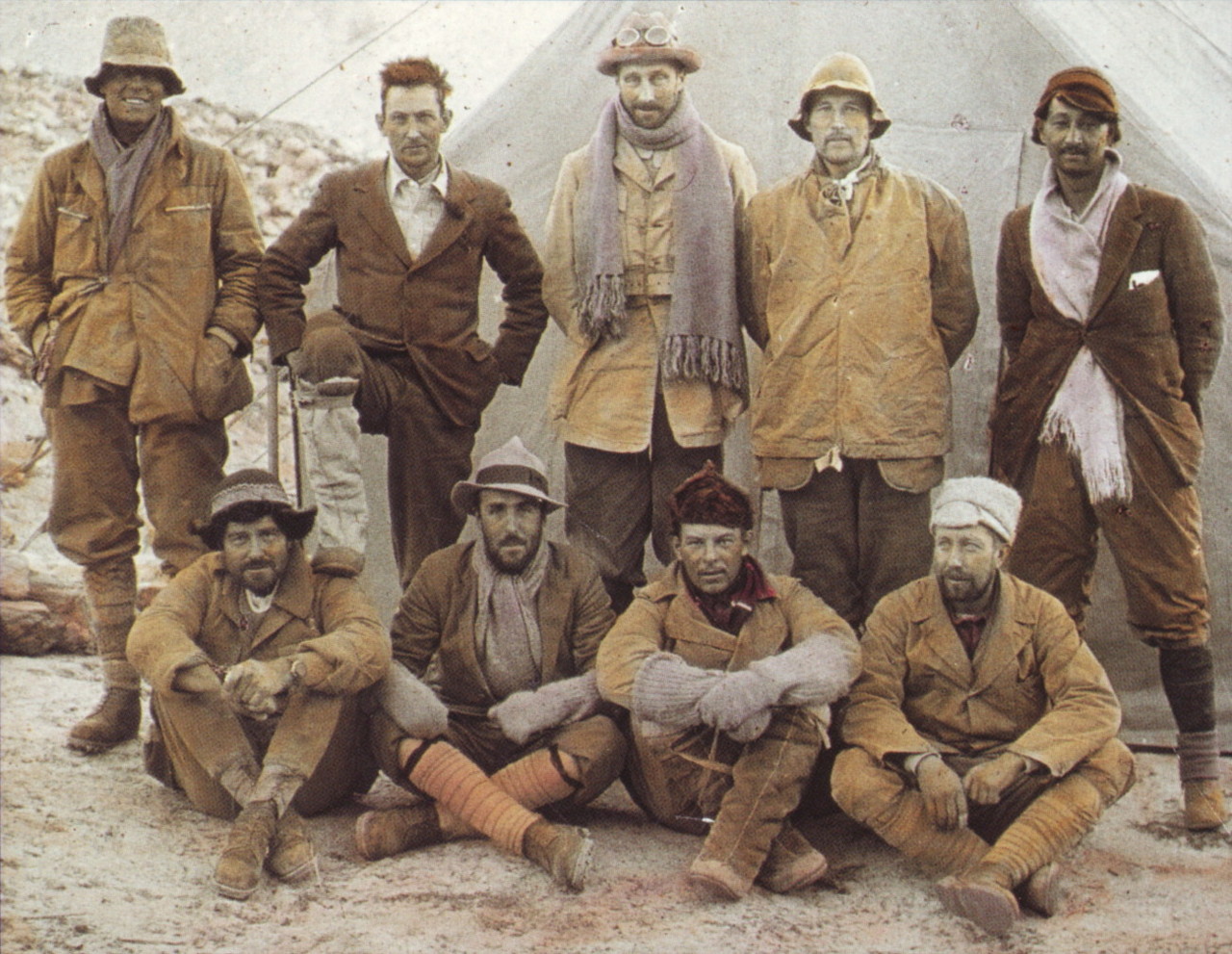

The 1921 expedition © Sandy Wollaston

The 1921 expedition © Sandy Wollaston

Back row: Guy Bullock, Henry Morshead, Oliver Wheeler, George Mallory.

Front row: A.M. Heron, Sandy Wollaston, Charles Howard-Bury and Harold Raeburn.

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Howard Bury (40) leads the group: nine members in all. Progress proved difficult. On arrival at Tingri in mid-June, relations between Mallory and Howard Bury deteriorated. Almost everything separated them: age, physical appearance, political stance, Himalayan experience...

From mid-June to mid-August, Mallory and Bullock, one of the participants, circled the mountain. They ascended the Rongbuk West Glacier, climbed the slopes of Lho La (6,006 metres) and set their sights on the then forbidden South Face (Nepal). Mallory soon spotted the North Col and Northeast Ridge, the obvious route to the summit. But finding the route to the North Col proved mysterious. In the absence of maps, the ascent of the East Rongbuk glacier eluded their sagacity: a simple torrent from an adjacent valley was not enough of a clue.

The expedition then skirted the mountain from the east, climbing up the long Kharta valley to reach the Lakpa La (6,849 m) on August 18: before their eyes, the East Rongbuk glacier and the slopes, finally accessible, of the North Col. Because of the monsoon, they had to wait until September 23 to descend the slopes of Lakpa La and set foot, 350 metres below, on the East Rongbuk glacier.

At 11:30 a.m. on September 24, Mallory, Bullock and Wheeler, accompanied by three porters, reached the North Col (7,010 m). The strong wind prevented them from going any further this season, but the road to the summit opened up before them.

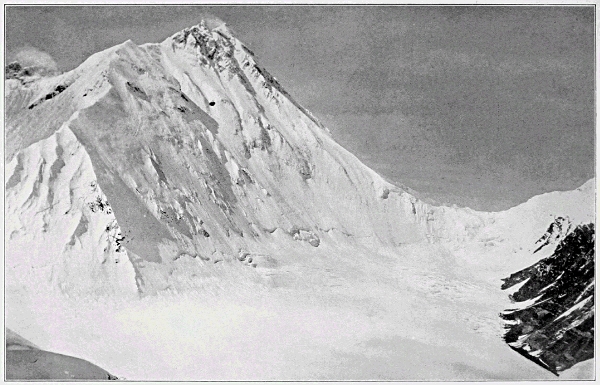

North pass seen from Lakpa La © Royal Geographical Society

1922: Mallory, not yet a myth, already a hero

1922 marks the first serious attempt on Everest and the first use of oxygen at altitude. Brigadier General George Bruce was entrusted with leading the thirteen participants, including, of course, Mallory. Fifty Nepalese, a hundred Tibetans and three hundred yaks formed the caravan. Objective: to climb the mountain before the monsoon arrives.

This time, they found access to the East Rongbuk glacier. On May 13, Mallory and Somervell set up Camp IV at the North Col; on May 20, Camp V at 7,230 meters. To date, the maximum altitude reached by man, without oxygen, is 7,498 meters. The record is approaching.

May 21: Mallory, Norton and Somervell, without oxygen, break the fateful 8,000-meter barrier and reach 8,225 meters, demonstrating the then controversial human ability to adapt to altitude. On May 27, Bruce and Finch improved their score to 8,326 meters, this time with oxygen. The key to their success could lie in this providential contribution.

June 7: final attempt, Mallory wants to try again with oxygen. Tragedy. On the way up the steep slopes of the North Col, an avalanche sweeps down the roped party. The result: seven Sherpas swallowed up. Back to England.

1923: it took several months to raise the funds and obtain the authorizations for the next departure.

1924: Mallory and Irvine: the legendary rope party

A good knowledge of the mountains, an experienced team and plenty of oxygen: these were the ingredients for success.

At the same time, a newcomer was about to make a name for himself. Only 22 years old, Andrew Irvine, an accomplished athlete, gets on famously with Mallory. At 38, he's convinced of success and in Olympic form. Bruce, once again expedition leader, suffers a serious bout of malaria on the Tibetan plateau and gives way to Norton. Norton proves to be a perfect leader of men, as well as an outstanding mountaineer.

The 1922 expedition © JB Noel

The 1922 expedition © JB Noel

Back row: Andrew Irvine, George Mallory, Edward Norton, Noel Odell, John MacDonald.

Front row: Edward Shebbeare, Geoffrey Bruce, Howard Somervell, Bentley Beetham.

21 May: Camp IV established on the Col Nord. This was followed by a period of severe bad weather, forcing the perilous rescue of four carriers who had lost their way on the North Col. Finally, on 1 June, Bruce, Mallory, Norton and Somervell left camp IV. Camp V at 7,600 metres. But the porters had had enough. Bruce and Mallory descend to the North Col, then to Camp III.

3 June: Norton & Somervell take over and Norton convinces three porters to bring their heavy equipment up to 8,170 metres (camp VI). Norton and Somervell demonstrated that humans could sleep at such an altitude without supplemental oxygen.

4 June: the two climbers, without oxygen, reached an altitude of 8,530 metres. Somervell, exhausted, left Norton to continue alone. At 8,573 metres, in unstable powder snow, he too had to end his ascent. Back to camp IV, then to base camp. The same day, Mallory and Irvine climbed back up to the North Col. This time with oxygen. Mallory chose Irvine, among others, because of his ability to handle oxygen equipment.

5 June: Mallory and Irvine arrive at Camp V, joined by Odell, who is there to support the two climbers.

6th June: Mallory and Irvine climb to camp VI.

7 June 1924: Mallory and Irvine set off for the summit. Odell, then in camp V, saw them briefly at the foot of the second step (8,500 m). They disappeared into the mist, never to be seen again. Could they have reached the summit?

Their disappearance incurred the wrath of the Tibetan authorities: the Dalai Lama refused to issue any further authorisations. A momentary end to "History".

Last known photo of Mallory & Irvine leaving Camp IV.

Shipton and Tilman: key players in the success story (1933-1938)

1933: the thirteenth Dalai Lama finally agreed to issue a new permit. The Everest Committee appointed Hugh Ruttledge, an eminent member of the India Civil Service (the ENA of the time!), to manage operations. Two leading figures in British mountaineering, Eric Shipton and Franck Smythe, winners in 1931 of the Kamet (7,756 m) in the Garwhal Himalayas, were also selected. Finally, Win Harris, winner with Shipton of the double summit of Mount Kenya, and Bill Wagger, a mountaineer and geologist replacing Odell, who was unavailable at the time, completed the team.

The appalling weather conditions in the spring of 1933 hampered progress. In the end, on 30 May, only Win Harris and Bill Wagger managed to reach the highest point reached by Norton in 1924. The weather was again miserable, forcing them to abandon. Significantly, on the way down, below the north-east ridge, they found an ice axe that most probably belonged to Irvine.

A legendary figure emerged from the team of porters from Darjeeling: Ang Tharkay, a veritable icon among the Sherpas. He took part in the French adventure to Annapurna in 1950 and sponsored Tensing Norgay, the future winner of Everest.

1934: new negotiations with the Tibetan government. At the end of the year, two authorisations arrived: one for 1935, the other for 1936. There wasn't enough time to get organised.

1935: a new reconnaissance, carried out by a small team of five men, led by Eric Shipton, with a very low budget. Another famous participant was Bill Tilman, an explorer and mountaineer already well known for having reached the Nanda Devi sanctuary in the Garwhal Himalayas in 1934, in the company of Eric Shipton. Tensing Norgay enters the scene as a young porter.

Main mission for this year: to test new materials in preparation for the 1936 assault. Shipton takes the first photo of the West Combe (south face), taken from Lho La. Progress stopped at the North Col. 26 virgin summits were climbed in 60 days! Despite the good results achieved at little cost, the Everest Committee returned to colossal budgets and resources the following year.

1936: a new expedition with a very big budget. Eric Shipton took part. Tensing Norgay also took part, still as a porter. Disastrous weather conditions halted any attempt beyond the North Col.

1938: After so many failures, the public was beginning to tire. The austerity of the time was hardly conducive to big budgets. The Tibetans granted authorisation for 1938, and Bill Tilman and Eric Shipton, the two apostles of light expeditions, set off once again. A small budget for a solid team of experienced Himalayan climbers. For the third time, Tensing Norgay got a job as a porter. This time, he climbed to camp VI (8,300 m) with another Sherpa, demonstrating his ability to reach the summit. Once again, the monsoon, with its snowfalls and violent winds, interrupted the joint efforts.

.png)

Bill Tilman on the 1938 expedition (left) and Eric Shipton (right)

Bill Tilman on the 1938 expedition (left) and Eric Shipton (right)

The war came in 1939, putting an end to the various attempts. With the end of hostilities, the Tibetans had to beg for another permit. All the more so since, with the independence of India proclaimed on 15 August 1947, the British were no longer the only masters on board: other pretenders were showing their noses!

Finally, the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950 definitively closed access to the North Face. In all, the British led seven expeditions to the North Face of Everest, without success. Eric Shipton's wish, expressed in 1920 to the newly-formed Everest Committee: "I hope to see an Englishman standing first on the summit of Everest", has yet to be fulfilled.

Will the eternal Sisyphus of the "British lion" overcome the curse that seems to follow him?

End of Part 1.

Read more: The conquest of Everest: 50 years to reach the roof of the world - Part 2

Join the next Everest climb via the Nepalese South Face or the North Tibet side.

Everest 8,848 metres from Everest Base Camp, Tibet, China. David Ducoin

Everest 8,848 metres from Everest Base Camp, Tibet, China. David Ducoin

Expeditions Unlimited blog

Expeditions Unlimited blog