The wind. The terrible Tibetan wind. Breath of the Gods, destructive breath. It insinuates itself between all clothes, freezing the slightest patch of skin exposed to its bite. On this night in October 1954, four men, who had already imagined themselves on the summit of the "Goddess of Turquoise", had a painful experience. Hoops broken, tents torn to shreds. The ease with which they overcame the major obstacle on the route, a bar of seracs that even the great Eric Shipton had to admit defeat before, led them to believe that success was easy. Victory on Cho Oyu would have to come from the frozen fingers of Herbert Tichy, accompanied by his friend Sherpa Pasang Dawa Lama. Here's a look back at the Austrians' success.

See all our climbs above 8,000 meters.

Four 8,000s for Austria

From 20 September to 19 October 1954, Cho Oyu, North-West Face: in exactly 30 days from Namche Bazar, the fifth summit of over 8,000 metres to be climbed by man fell into the hands of the Austrians. Perhaps the best mountaineers of the post-war era.

Their eloquent record speaks for itself: four 8,000. No other nation could match them.

- 1953 Nanga Parbat - 8,126 m

- 1954 Cho Oyu - 8,201 m

- 1956 Gasherbrum II - 8,035 m

- 1957 Broad Peak - 8,047 m

Quantity, but also quality. At a time when an ascent to 8,000 metres is synonymous with heavy expeditions, Herbert Tichy's ascent is in stark contrast, bringing us back to the ethics dear to Shipton. Three Westerners, seven Sherpas and no oxygen. A gradual and effective acclimatisation from Nepal, via the Nangpa La pass (5,716 m). And the key passage of the route, the famous serac bar, climbed by Pasang Dawa Lama at the head of the rope party. Because unlike Her Majesty's subjects, Herbert Tichy considers the Sherpas to be equals.

This was one of the first expeditions to a major summit in which the Sherpas played a leading role. At Cho Oyu, they were true members of the team, playing a leading role in decision-making about the ascent.

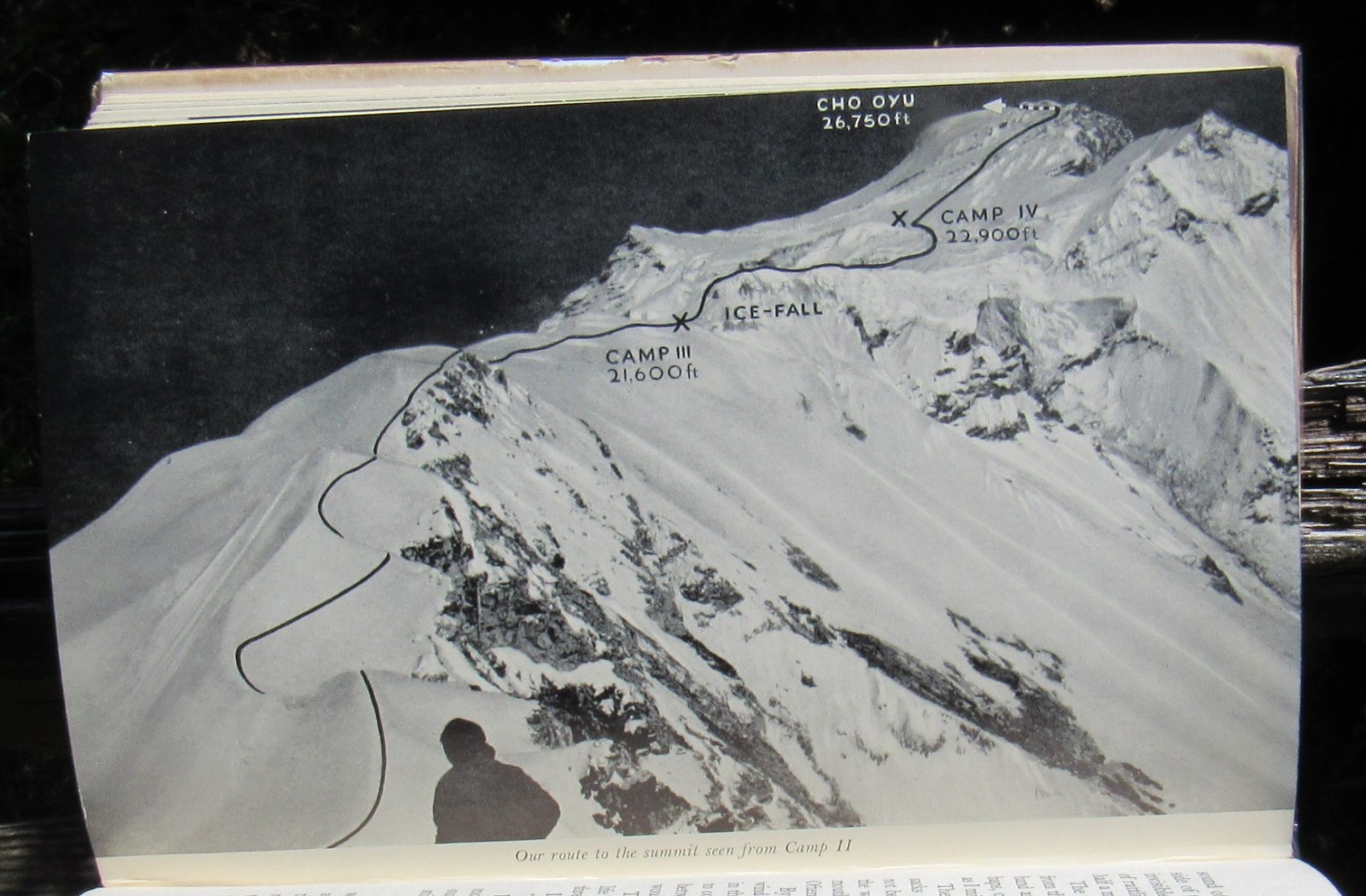

The north face of Cho Oyu, seen from the Tibetan plateau

The beginnings

The English could have had a claim to the conquest. In November 1951, at the end of Eric Shipton's reconnaissance of the Nepalese side of Everest, Bourdillon and Murray, who had been smuggled over from Nepal to the Tibetan side, took a close look at Cho Oyu. Murray: "This north-west face was the most promising route I'd ever seen on any major Himalayan peak. It was engaging. It was safe. The snow was in perfect condition. There was no wind. All we needed was food, equipment and Sherpas". They were unable to see the serac bar in the lower third, hidden behind a rocky spur.

At the end of 1951, to the great displeasure of the former British Empire, the Nepalese government granted the permit to climb Everest to different nations: 1952 to the Swiss, 1953 to the British and 1954 to the French. So as not to lose a year, the British launched an expedition to Cho Oyu in the spring of 1952. They had in mind not only the virgin summit, but also the idea of testing equipment and climbers for the 1953 assault on the roof of the world. Once again, Shipton was in charge. Edmund Hillary, future Everest conqueror, was part of the team. Beyond the Nangpa La, they were marching into forbidden territory: Communist soldiers could easily seize them.

A bar of seracs deemed impassable at 6,550 m, lung ailments and the fear of being taken prisoner by the Chinese: contrary to his habit, Shipton did not insist. This failure cost him his place as leader of the 1953 Everest expedition.

The same considerations (clandestine ascent) no doubt justified Herbert Tichy's decision to set off with a very small team, without "laying siege".

The team: Austrian and Nepalese-Indian

Viennese mountaineer, geologist, journalist and writer, Herbert Tichy (42) knows Asia well. In 1935, he travelled the road between Austria and India by motorbike. Disguised as an Indian pilgrim, he entered the Tibetan Far West. His goal: to reach the sacred mountain, Mount Kailash. The route passes at the foot of the imposing Gurla Mandhata (7,694 m), whose snows are reflected in the waters of Lake Manasarovar. He attempted to climb it with one of his porters. At 7,200 m, fresh snow and bad weather forced them to turn back.

He was joined by Sepp Jochler (31), another experienced mountaineer who had climbed the Eiger for the eighth time with Herman Buhl.

The third man, Helmut Heuberger (31), a geographer and keen traveller, came to the rescue.

Sherpa Pasang Dawa Lama (42), the real hero of the adventure, is responsible for its success. Born in Darjeeling and destined to become a monk, he became a mountaineer. He first climbed Chomolhari (7,134 m) in Bhutan with the British in 1937. In 1939, without oxygen, he climbed to 8,370 m on K2. In 1951, he participated brilliantly in the reconnaissance of Everest led by Shipton. In 1953, already with Herbert Tichy, he climbed several 6,000 meter peaks in the remote Patrasi Himal massif (far west of Nepal). On Cho Oyu, his experience, talent and stamina worked wonders: to bring supplies, he covered 4,800 m of ascent in two and a half days.

Photo from Herbert Tichy's book “Cho Oyu : by favour of the gods” - 1957

Pasang, first of the roped party

After arriving safely at base camp on 29 September, they moved on to camp after camp.

Camp I at 5,800 m. Camp II at 6,150 m. Poorly acclimatised, Sepp Jochler returned to camp I. Helmut Heuberger was in charge of logistics from the base camp.

Herbert Tichy and the Sherpas continue to advance. They reached the foot of the serac bar at 6,550m. Impatient Pasang took the lead. In just a few hours, with all the skill of an Alpine guide, he completed 300 m of glacier climbing, opening the way to the summits. Camp III at 7,000 m. Tichy, Pasang and two other Sherpas settle in for the night. For Pasang and Tichy, the summit is within reach.

The serac bar at 6,650 m

Hanging victory

The man proposes, the mountain disposes. During the night, the terrible westerly wind picks up and blows like a hurricane. The masts bend and the tents threaten to blow away. Tichy rushed out and forgot to put on his gloves. Within minutes, his fingers were frozen and unusable. The four men laboriously made their way down to Camp I, where the entire team regrouped. Big council. Prudence would dictate that they give up. But Kathmandu is three weeks away. Herbert prefers to stay and be looked after by Helmut. Pasang and Sepp could still make it, if the wind died down. The clear, cloudless sky is a cause for optimism.

Race to the top

At this already critical moment, an unexpected rivalry has been added. They were joined on the mountain by a Franco-Swiss team (four Swiss men and Frenchwoman Claude Kogan), led by guide Raymond Lambert (Everest 1952). Having met in Kathmandu at the start of the trip, they had announced that they were going to attempt Gaurishankar (7,134 m). Unable to climb this peak, they came to test themselves against Cho Oyu. They too were surprised to find the Austrian team, as at their previous meeting they had mentioned a scientific expedition, without revealing their plans to climb Cho Oyu. The Swiss, thinking they had found the free ground, were bitter. Two of them want to take advantage of the momentary failure of the Austrians to launch their own assault.

Finally, Raymond Lambert and Claude Kogan, fair play to them, acknowledge the opposing team's "priority". They were allowed one more attempt. Beyond that, Lambert and his companions felt free to launch their own assault.

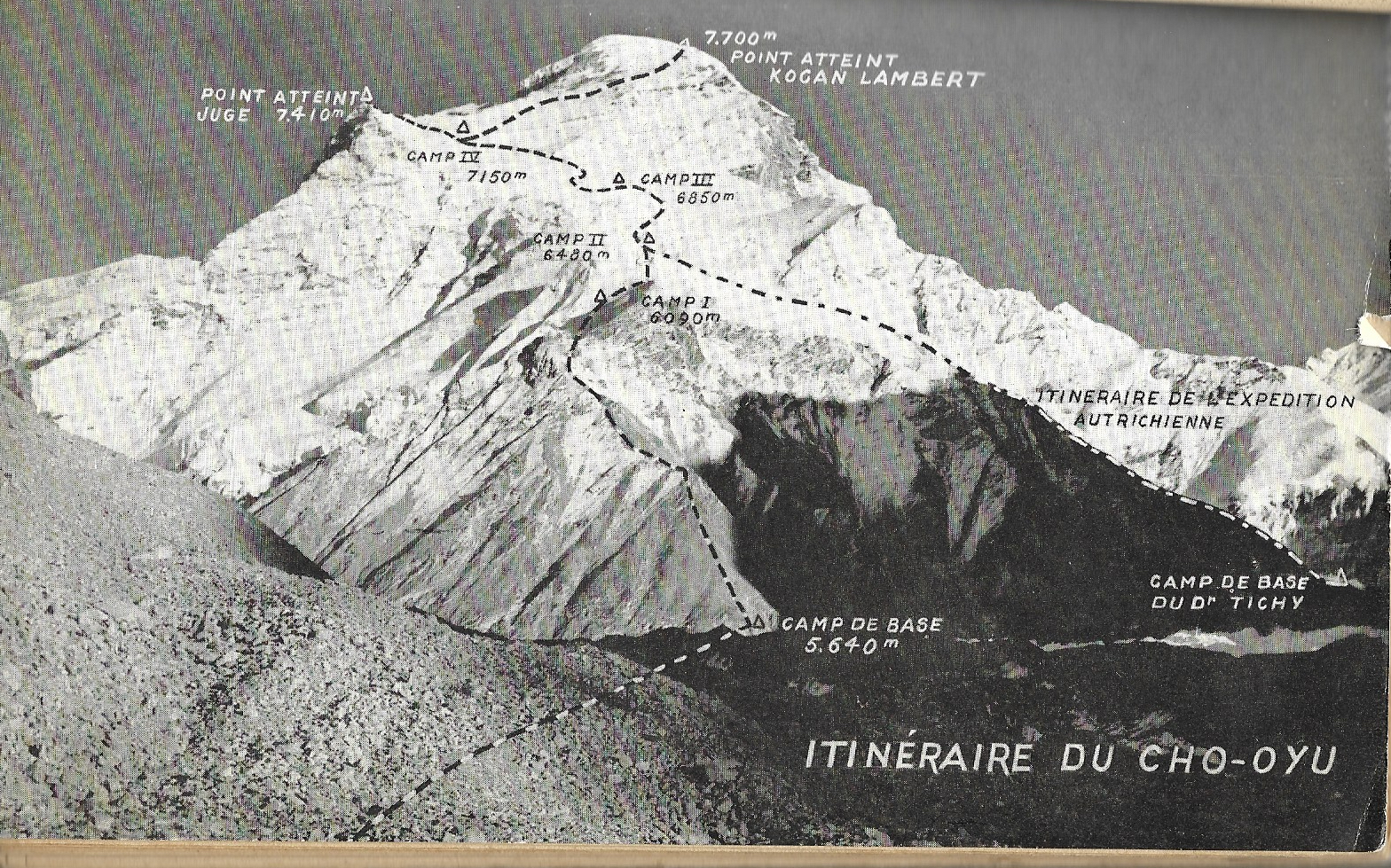

Itineraries of the two 1954 expeditions, Austrian and Swiss. The route now follows the Swiss route © Tichy

Victory at last

Spurred on by these unlikely competitors, the whole of Tichy's team climbed back up to the foot of the seracs, where they dug an igloo to protect themselves from the cold. Tichy, with his hands wrapped in several layers, can hardly help, but he can't stay alone in Camp I either, because he's too disabled.

Despite his frostbite, and with Pasang's help, Tichy courageously reached camp III, where he decided to continue to the summit. He will not rope up. If he can't keep up, he'll return to camp.

19 October 1954: departure in the moonlight. Slowly, the three men climb. Pasang leads, Herbert follows, Sepp closes the way. On the long summit plateau, they took the last few steps, holding each other by the arm, to reach the real summit. Because Cho Oyu, unlike many other peaks, leaves room for uncertainty: not an indisputable peak, but a vast dome. It's not enough to say "I can see Everest, so I'm at the summit". Many long, tiring minutes pass before you reach the highest point, one foot in China, the other in Nepal. The only certainty is that, in good weather, you can see the horseshoe-shaped cirque of Nuptse - Lhotse - Everest, less than twenty kilometres away as the crow flies.

Epilogue

When Lambert heard of their success, he described it as a "heroic folly", thinking of Herbert Tichy and his fingers already in a bad way. With Claude Kogan, they had to give up their success, pushed back 450 m from the summit by the icy wind. In 1959, Claude organised the first international women's expedition to the Himalayas, on the same Cho Oyu. She disappeared during the ascent, swept away by an avalanche.

Climb Cho Oyu at 8201 meters in Tibet

Climb Shishapangma at 8027 meters in Tibet

Expeditions Unlimited blog

Expeditions Unlimited blog