3 June 1950, 2pm, 8,091m. Maurice Herzog and Louis Lachenal photographed themselves at the summit of the first 8,000-metre peak ever climbed by man. A few minutes of glory, but at what price? While Maurice Herzog survived the terrible tragedy of the descent relatively unscathed, gaining fame and honours, the same cannot be said for Lachenal, who was condemned to silence in the name of the honour of the Republic. To distinguish between patriotic heroism and human reality, to disentangle the true from the false, we need to take the time to look seriously at each person's writings in order to go beyond the myth.

See all our climbs above 8,000 meters.

Tibet closes, Nepal opens

Long withdrawn into itself, having even managed to escape the domination of the British Raj, Nepal timidly opened its doors in 1950. But not out of altruism. The brand new Communist regime that had come to power in China was laying siege to Tibet, which was of great concern to the Nepalese monarchy. Opposed to the old British colonial power, King Tribhuvan preferred to turn to the USA.

Dillon Ripley, a renowned ornithologist and former officer in the OSS (later the CIA), was the first to travel through Nepal in 1947 and 1948 on scientific expeditions.

"Why should tourists come to Nepal when all we have are mountains?

The origins of tourism in Nepal can be traced back to an astonishing figure: Russian refugee Boris Lissanevitch, a former ballet dancer and owner of the very select ‘300’ club in Calcutta. A charismatic figure, he established a bond of trust with King Tribhuvan, who made frequent visits to the capital of the British Raj. Boris became the first foreigner to be allowed to live in Kathmandu, where he opened the Royal Hotel, for many years the only luxury hotel in the valley.

When Boris suggested to King Tribhuvan in the early 1950s that it might be possible for Nepal to attract large numbers of tourists, the king replied: ‘I can see why tourists want to visit a place like Calcutta. But why should they come to Nepal, where all we have are mountains?

The French beat the English to the punch

For once, it's not usual. Much to the chagrin of the British Alpine Club, the first permit to climb an ‘8000+’ peak in Nepal was granted to the French Alpine Club in 1950. Dhaulagiri I (8,167 m) and Annapurna I (8,091 m) were offered to the Club on a platter. The only probable explanation for this favourable treatment was Nepal's political will to attract allies who were less enterprising than the British.

The cream of French mountaineering

In post-war France, mountaineers were in short supply. The Comité de l'Himalaya, chaired by Lucien Devies, selected the team.

Maurice Herzog (33), the expedition leader, was chosen above all for his organisational and leadership skills. Admittedly, his list of climbs could not compete with that of the ‘pros’, but in the Himalayas in 1950, you didn't tackle difficult routes. Louis Lachenal, Lionel Terray and Gaston Rébuffat, all aged 29, high mountain guides and members of the prestigious Compagnie des Guides de Chamonix, formed the spearhead of the team. Jean Couzy (27) and Marcel Schatz (28), two promising young mountaineers, formed a back-up team, essential for the many reconnaissance missions to be carried out. Marcel Ichac (44), cameraman, and Jacques Oudot (37), surgeon, completed the team.

Francis de Noyelle (31), a young diplomat based in New Delhi who spoke Hindustani, was appointed liaison officer. A real linchpin of the expedition, his diplomatic skills enabled him to get a daily weather report broadcast on All India radio. A real weather router before its time.

Eight Sherpas accompanied them under the direction of sirdar Ang Tharkay (43), a veteran of many expeditions.

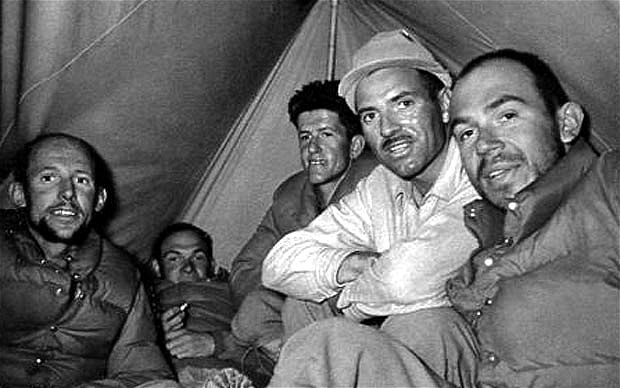

Camp 2 5,900 m. From left to right: Louis Lachenal, Jacques Oudot, Gaston Rébuffat,

Maurice Herzog, Marcel Schatz © Marcel Ichac / L de Boissieu Ichac

False hopes on Dhaulagiri

On 30 March 1950, the expedition left Paris. On 21 April, they reached Tukuche (2,600 m), in the upper valley of the Kali Gandaki. They were the first Westerners to penetrate so far into the mountains of Nepal. While Dhaulagiri rises up in all its splendour, Annapurna is hidden behind the high barrier of the Nilgiris (7,061 m), which defends access to it. The map they had at their disposal was wrong, and they were unable to find an obvious route to Annapurna.

For three weeks, they focused their efforts on Dhaulagiri. The south face, south-east ridge, east glacier and north-east ridge were scouted in turn, to no avail. All the routes considered were far too difficult. Once they had skirted around the tip of Tukuche, they hoped to observe the north face: once again, the map proved to be wrong. They discovered the ‘Hidden valley’ and then reached the ‘French pass’ from where they could finally see the north face. To their great disappointment, the ridge and the north face seemed equally insurmountable.

A lama plays oracle

A Buddhist monk, passing through the base camp, acted as an oracle: ‘Dhaulagiri is not in your favour, it's better to abandon it and turn your efforts to the other side, towards Muktinath’. On 8 May, Herzog, Rébuffat and Ichac climbed back up the valley and crossed the Tilicho pass, hoping to find access to the north face of Annapurna. But the Grande Barrière, a series of summits that culminate in the Tilicho (7,134 m), blocks the access to the north face.

14 May ‘council of war

The monsoon is forecast for the first week of June. Time is running out. If Dhaulagiri is proving to be an impregnable citadel, there's still Annapurna. But they still had to find the mountain! Following a veritable ‘council of war’, Herzog and his companions forced their way through the deep gorges of the Miristi Khola. Finally, on 17 May, a base camp was established at the foot of the north-western spur of Annapurna. This was followed by five days of increasingly difficult efforts and technical difficulties on the spur. On 22 May, the climb was a failure. Back to base camp.

Ten days to succeed

The situation was serious. The monsoon was approaching. On the basis of a hunch, Rébuffat and Lachenal went around the foot of the spur: the north face, despite the high risk of avalanches, seemed practicable. This time, they were on the right track. In record time, four camps were set up. On 28 May, camp 4 at 7,150 m, just below a formidable curved ice cliff they called ‘la faucille’. Above it, gentle snow slopes seemed to lead to the summit.

.png)

The North Face of Annapurna, the 1950 route © Ed Guérin

Herzog : “c’est tout ou rien”

On 1 June, in top form, Lachenal and Herzog climbed to camp 4, dismantled the tents and set them up in the upper camp 4, above the sickle. On 2 June, Herzog, Lachenal and four Sherpas went up again and set up a precarious camp 5. Due to lack of space, the Sherpas returned to the upper camp 4. Lachenal and Herzog remained alone at camp 5, at 7,440m. They still had 650 m to climb.

Throughout the night, the wind blew like a storm. Clinging to the tent pole, which bent under the gusts and the weight of the snow, they didn't sleep a wink. On the morning of 3 June, nauseous, they set off for the summit without eating or drinking. From that moment on, myth and reality became intertwined.

We can wonder about their physical performance. Terray: ‘Do we owe this miraculous form to the regular intake of drugs prescribed by Oudot?

Herzog to Terray, the day before: ‘We're going up,’ I said without hesitation. When we come back down, the summit will have been reached. It's all or nothing.

Later, Lachenal would write: ‘I knew my feet were freezing, that the summit was going to cost me. For me, this race was a race like any other, higher than in the Alps, but nothing more. If I had to leave my feet there, I didn't care about Annapurna. I didn't owe my feet to French youth".

And further on: ‘So I wanted to go down. I asked Maurice what he would do in that case. He told me he would continue. It was not for me to judge his reasons; mountaineering is too personal. But I felt that if he went on alone, he wouldn't come back. It was for him and for him alone that I didn't turn back".

Lachenal, a guide with the Compagnie des Guides de Chamonix, could not go back down and let Herzog continue alone. If Herzog didn't come back, the guide would be shamed and disgraced. At that precise moment, Lachenal had no choice.

The summit, prelude to catastrophe

At 2 p.m. on 3 June 1950, the nation could be proud. They had won. And without oxygen (they had refused to bring any from France).

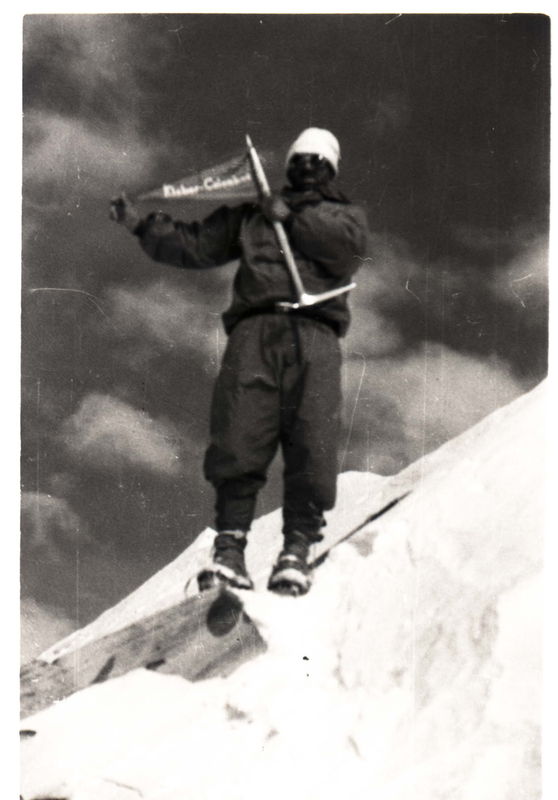

Maurice Herzog at the summit, with the flag of the main sponsor: Kléber-Colombes

Photo by Louis Lachenal © Yves Ballu

But from that moment on, everything that could go wrong did. Herzog, in circumstances that were not entirely clear, lost his gloves. Lachenal, who was rushing downhill, lost his balance and fell... The antics, which could have been definitive, miraculously came to an end 100 meters below camp 5 where Terray and Rébuffat had climbed. Herzog, his hands and feet frozen, reached the camp alone. Terray heard faint calls and rushed down the slope to help his long-time companion. Terray: ‘With no ice axe, no headgear, no gloves and only one crampon left, Lachenal has obviously just had a serious fall. Night came. Obsessed by his frostbite, Lachenal wanted to descend at all costs. Terray had great difficulty in forcing him to return to camp.

The next day, the storm raged. They had to go down if they wanted to survive. Lachenal, whose feet were deformed by the frost, couldn't get his shoes on. Terray gave him his own shoes (two sizes larger) and, gritting his teeth, put on Lachenal's shoes. An act of self-sacrifice if ever there was one, but the most incredible thing was that Terray didn't get frostbite!

They should have brought bamboo stakes with flags to plant on the way up. But they didn't. A mistake with far-reaching consequences. They got lost and wandered the slopes for many hours before settling on the inevitable: an improvised bivouac in a crevasse. Blinded in the storm, Terray and Rébuffat took off their glasses to try and find their way. A few hours later, they were diagnosed with ophthalmia.

Leave me alone, I'm dying

The next day, they were rudely awoken by a powder avalanche. Half buried, they struggled to find their boots and the rest of their equipment. Terray and Rébuffat, half-blind, thought that visibility was still zero. Despair gripped them. Lachenal struggled to extricate himself from the crevasse. When he did, in his socks in the snow, he shouted: ‘It's sunny, it's sunny! We're saved! Herzog couldn't take it any more: ‘Lionel, it's over, I've got no strength left, leave me alone, I'm going to die’. Still lost, they don't know where to turn. Suddenly, a miracle happened: above them, Schatz appeared. Camp 4 was only a couple of hundred meters away: they were saved.

The terrifying return

On 11 June, they left the base camp in pouring rain: the monsoon had arrived. A porter was killed on the dangerous crossing above the Miristi Khola. Lachenal and Herzog, sometimes carried on a bad stretcher, sometimes on men's backs, suffered martyrdom. Oudot, the surgeon, did his best to relieve their suffering. But they had to wait until they were back in Tukuche to receive the first serious treatment. Over the next few days, Oudot made daily cuts into the rotting flesh, to the howls and cries of the wounded. The walk along the Kali Gandaki was a long ordeal. On 1 July, Lachenal, riddled with fleas, wrote: ‘It's been 2 months since I washed my hands’. Finally, on 16 July, they left New Delhi and landed at Orly on the 17th.

Lachenal being carried by Terray on arrival at Orly on 17 July 1950

The genesis of the myth

Herzog, on his hospital bed in Paris, dictated his book to his brother Gérard, a journalist and writer, himself a mountaineer. The book, the starting point of the myth, is the fruit of Maurice Herzog's memory and his brother's literary talent. The logbook of Louis Lachenal, the only member of the team to keep a day-to-day diary, can be contrasted with it without hesitation. In the name of state policy, his account was never published. On 25 November 1955, the accidental death of Louis Lachenal during the descent of the Vallée Blanche put an end to all controversy. We had to wait until October 2020 to read this poignant, unheroic account. This is thanks to the book ‘Rappels’, published by Paulsen-Guérin, at the instigation of Louis Lachenal's son. It is a raw, even disturbing account. The description of the suffering endured after the descent and on the long walk home leads to a haunting question: was it worth it?

Find out more about the itinerary for this ascent below:

Text and animation by Didier Mille.

Climb Annapurna at 8091 meters in Nepal

Climb Manaslu at 8163 meters in Nepal

Expeditions Unlimited blog

Expeditions Unlimited blog